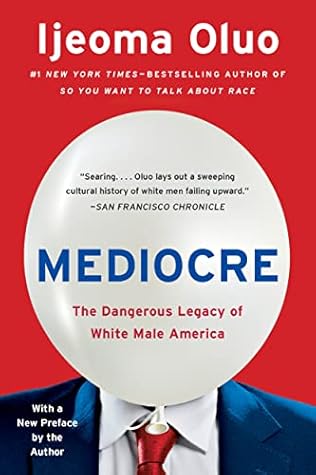

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Ijeoma Oluo

Read between

March 14 - March 16, 2021

White male mediocrity seems to impact every aspect of our lives, and yet it only seems to be people who aren’t white men who recognize the imbalance.

How can white men be our born leaders and at the same time so fragile that they cannot handle social progress?

The image of the ideal white man—the bold and confident ones we end up idolizing, giving promotions to, electing to office—that image is often the epitome of mediocrity. And when entrusted with these positions of power, such men often perform as well as someone with mediocre skills would be expected to: we see the results in our floundering businesses and in our deadlocked government. Rather than risk seeming weak by admitting mistakes, white men double down on them.

The man who never listens, who doesn’t prepare, who insists on getting his way—this is a man that most of us would not (when given friendlier options) like to work with, live with, or be friends with. And yet we have, as a society, somehow convinced ourselves that we should be led by incompetent assholes.

But over generations, feminism has grown and changed. There is still what is called “white feminism”—the tendency for white feminists to center themselves at the expense of women of color—but at least now we have a name for it. And in naming it, we can think about how to move beyond it.

We find racism in our systems when we look at what the system produces. When we find systems with outputs that negatively affect people of color in a way or to a degree that they do not affect white people, we have a racist impact that can be tied to a racist cause.

A political movement that focuses on class and ignores the specific ways in which race determines financial health and well-being for people of color in this country will be a movement that maintains white supremacy, because it will not be able to identify or address the specific, race-based systems that are the main causes of inequality for people of color. Health care discrimination, job discrimination, the school-to-prison pipeline, educational bias, mass incarceration, police brutality, community trauma—none of these issues are addressed in a class-only approach. A class-only approach will

...more

What exactly do people who aren’t white men have that could be more inclusive of white men? We do not have control of our local governments, our national governments, our school boards, our universities, our police forces, our militaries, our workplaces. All we have is our struggle. And yet we are told that our struggle for inclusion and equity—and our celebration of even symbolic steps toward them—is divisive and threatening to those who have far greater access to everything else than we can dream of. If white men are finding that the overwhelmingly white-male-controlled system isn’t meeting

...more

At every college I went to—every single one—at least one teacher of color broke down in tears describing their struggle to advocate for their students of color in such a hostile environment. Higher education is not the racial utopia that Republicans are scared of. It is not some bizarro world where students of color wield power over white students and faculty. It is a white supremacist system at its core, like all our other systems are.

My education has served me well in this career, even if it was not what I originally imagined for myself. It also, like a job as an analyst likely would have, fits my introverted yet very opinionated personality. I spend a lot of time observing, thinking, commenting. I do not have to compromise my principles or soften my message to make friends or keep a job

It should be enough that this is hurting us. It is insulting that I have to point out the ways in which these issues also hurt white Americans in the hopes that I might get more people to care.

In introducing the legislation, Pressley argued, “For far too long, those closest to the pain have not been closest to the power, resulting in a racist, xenophobic, rogue, and fundamentally flawed criminal legal system,” adding, “Our resolution calls for a bold transformation of the status quo—devoted to dismantling injustices so that the system is smaller, safer, less punitive, and more humane.”

In discussing how hard the four of them have had to fight during their time in D.C., Omar sounded defiant and determined: “I think we have a beef with almost anyone here because there’s a lack of courage. It seems like we’re all radical because we deeply care about the people we represent and we want to throw down for them.”

The following year, enrollment at Mizzou was down sharply, especially of Black students. This isn’t because Black prospective students disagreed with the protests. Black students who decided not to attend the previously well-respected school said that the racism highlighted on campus had turned them off. Some Jewish prospective students said that hearing about swastikas being painted on walls kept them away. And some white prospective students said they didn’t want to be associated with a university so widely known to be racist.

I'm shocked year after year that this isn't the case at Cal Poly in SLO. The bonds with white supremacy are strong here.

“It was shocking, because you have the idea where you are a brotherhood. When you have an issue outside of football and you’re looking for your brothers to be there for you, and when you find out they aren’t, that hurts a little bit.”

I know it's not comparable, because I'm not in mortal danger, but I'm always so disappointed when my colleagues reveal their unwillingness to examine their own biases and continue teaching rooted in white supremacy.

We must start asking what we want white manhood to be, and what we will no longer accept. We must stop rewarding violence and oppression. We must stop confusing bullies with leaders. We must stop telling women and people of color that the only path to success lies in emulating white male dominance.