More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 18 - September 22, 2022

I was uncomfortable enough binding down the body I had so I could be the boy I was. I barely understood Daisy doing it to be a particular kind of girl.

Daisy glanced toward me, one hand under her chin. That glance told me that if people like us wanted to make something of ourselves in a world ruled by men as pale as their own dinner plates, we had to lie. Daisy would help me make my way in New York. Her price would be the two of us erasing ourselves from each other’s blood.

“Every beautiful thing can be broken down into math,” I said. “There are numbers under all of it.” “Isn’t that a little cold?” he asked. “No,” I said. “It’s comforting. It means that underneath everything that’s ever moved you or that you’ve ever loved, there’s something real and irrefutable. There’s a lattice of numbers proving that it’s true, that it’s really there, that you didn’t just imagine all of it.”

There’s more money in selling dreams than in all the wheat futures in the world. Never forget that, Carraway.” “It’s Caraveo,” I said. “I’m doing you a favor here,” he said. “Back in Michigan, you be whoever you want. But here, you forget the family name. You’re Nick Carraway.”

“I remember all of it, right back to that first night,” Gatsby said. “When she laughed, it was like the inside of her was a church echoing the sound everywhere, like that was the perfect noise of the whole world. And the way she moved her hands … it was birds taking flight, that first moment of them on the air, every time. And I could see a life with her, this glorious kind of life I never imagined for myself. One I thought I could never have.”

“I wasn’t quick enough.” He said it not with bitterness but as a fact I needed to know. “I didn’t have anything to offer a girl like her back when we met. I thought I could though, one day. But while I was gone, she got too far ahead of me. She became that girl, that woman, she always dreamed of being, and I hadn’t gotten all the way to being that man. It took me too long to catch up. It took too long for the war to be over and for me to get back, and by the time I did, I still wasn’t that man even though she was that woman. I didn’t want to find her again until I had a version of myself worth

...more

My cousin needed to get away from Tom Buchanan. And if Jay Gatsby was the best chance to change her mind, I’d do anything he asked.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” “Oh, I couldn’t talk about it with anyone,” she said. “I could smile for all the pictures, but when anyone asked me about it, I just told them about the swimming and the getting to shore at dawn. That’s all they wanted to hear about anyway. I couldn’t talk about all of it, because then who am I? Daisy the drunk who fell off a boat.”

Was this what Gatsby had so loved about her? She was all the romance of a girl in a painting, adorned in sunset chiffon, standing against a sapphire-and-emerald night and reaching for the moon. She had been this way since we were growing up, always making flourishes out of wildflowers, setting the buñuelos in arrangements as intricate as houses of cards.

“Anybody would be happy to see you,” I said. His smile was a needle of sun piercing a gray scrim of clouds. And perhaps it was this, how he could be touched by so small a compliment, that made me understand all he’d stored up in his heart. This boy whose shoulders I held in my hands, I wanted him to have the shimmer of the whole world. And for him, it was all held in the dark honey of Daisy’s eyes.

I thought of kissing him in the way I imagined everyone must think of kissing someone who was this close and this beautiful. It was the way I should have thought of kissing girls but only did if I put my mind to it. But there was no putting my mind to this. Kissing Gatsby was a thought that slipped in like that knife of sun, sudden and bright.

You see, Nicky, boys are always falling in love with me, but I don’t much fall in love with them. I’ve always wondered if something was wrong with me, to tell you the truth,

Who knew that a couple of well-thrown-in words could make me seem at home among these men? It turned out Gatsby had known. He’d told me to use hectic instead of busy, slick instead of clever or smart. He’d taught me how to seem at ease among men who said the word white so meticulously it carried an extra breath.

Gatsby’s gardens were a place of ecstatic dancing, in which the whole world seemed to be having a gay time. The women had French bobs, and blush rounded the apples of their cheeks. The men flirted through pocket doors between green and gold rooms. Fingernails shined with paintings of butterflies and stars. The dresses were loose, the waists set low. But there was something daring about how many were sleeveless, how filmy the fabrics were, how many were shades of pink or beige or brown that nearly matched the skin.

I learned it was to my benefit to look a certain way. People treat a girl very differently depending on how she looks. Doors open that you didn’t even know could be doors because they always looked like walls.”

“She still may not choose you,” I said. “I can’t speak for my”—I stopped myself before I said my cousin—“my friend. My friend might not choose you.” “I know,” Gatsby said. “I just want her to be happy. I want her to know she has a choice.”

Gatsby looked back at me how any boy in the world would want to be looked at—as though there was such infinite possibility in me, such infinite light, that I was one endless, longest day of the year.

“Where are we?” I asked. “The gayest place in New York.” Gatsby pushed on a wood panel that turned into a door. “In more ways than one.”

“Have you ever heard of a lavender marriage?” “No,” I said, though I could now guess. “They’re very chic in the Hollywood sewing circles,” Gatsby said. “Marrying for appearances is much easier when both husband and wife are equally fond of and uninterested in each other.

The celebratory fever around us was the only explanation I had for why I kissed him. And it was the only explanation I could come up with for why he kissed me back.

Gatsby loved Daisy. I was Nick. I wasn’t the distant allure of a green light. I was close. I existed in the play script of Gatsby’s life for no reason except to facilitate his reunion with the girl he loved.

Was a boy like me even allowed to love another boy? What did that make me? I had parents who’d respected me telling them that I was a boy, and who’d helped me live as the boy I was. Shouldn’t that have been enough? Shouldn’t I like girls as more than friends by now?

Jordan Baker, the woman who was just as much a harbinger of Tom Buchanan’s nightmares as I was. Jordan Baker, the woman passing as white just as successfully and probably with just as much effort as Daisy. “Oh, Jordan,” I breathed out. “Oh, stop,” she said. “I don’t want your pity. Would you want mine?” “It’s not pity,” I said. “Well, I don’t want your admiration either,” she said.

“The problem is that she hasn’t truly reckoned with it, what it means to live as she’s living. She talks to her family, your family, as though nothing has happened, as though life is just as it was. I couldn’t do that. I had the conversations. Hard as they were, I had them. We had them. But she hasn’t done that with her family. I doubt she’s truly even done it with you.”

Most of the men like me I’d read about, the ones who had lovers at all, had lovers who were women. Some even had wives. Were there any who loved other men? Did those kinds of self-made boys exist? If I loved another boy, did that make me less of one?

But I knew what this was. His firm grip on me, the curt way he’d patted his hand twice against my back, the hold that was more strong than intimate. This was the embrace of friends, nothing more.

“You think I do all this for her,” Gatsby said. “This house. The parties.” “Don’t you?” I asked. “I’m more selfish than that,” he said. “How?” “Because this is how I forget,” he said. “This is how a lot of us forget.”

We came home to a world we didn’t know anymore and a country that didn’t know what to do with us and didn’t much care to. Boys like you and me knew we’d have to work harder to be considered men, and we’d still have to no matter what we’d done in the war. Black soldiers came back to a country that didn’t value their lives any more than the day they’d left, even though they’d just risked them for it.

Gatsby and I may have been nothing to men like Tom Buchanan, but men like that did not know we were as divine as the heavens. We were boys who had created ourselves. We had formed our own bodies, our own lives, from the ribs of the girls we were once assumed to be.

Some people wore their broken hearts with careful grace. I didn’t. The pieces of mine scraped against everything, and everyone could hear the grinding noise, even if they didn’t know what it was.

Before the end of the night, they would call it the fashion statement of the season. An upstart socialite had burst onto the social scene with a golfer whose style matched her skill.

Within days, newspaper columns would herald Jordan and Daisy as an illustration of the new age, one in which girls and women forged their own paths across ballrooms and into the world.

“The debut,” I said. “All of it. It was for you. To make you the debutante of the season.” “Oh, is that what it was for?” Her laugh was a cutting chirp. “Good of you to tell me. I’d be so lost without young men like you standing by to tell me things.”

Now her laugh was unguarded and piercing. “I’m sorry. I broke his heart?” “Didn’t you?” I asked. “You need to talk to Jay.” She glanced past me. “He needs to tell you the truth, and you need to hear it.”

“Men love beautiful, useless, expensive things. So I’m meant to be one. I’m not supposed to be anything but a beautiful little fool.”

I realized I’d been in love with her for a long time and hadn’t known it, and that she’d been in love with me for a long time and had known it. Maybe sometimes I’d known a little, when I saw the bloom of her lipstick on a champagne glass, or when she told me that bridal bouquets were getting so enormous I’d have to take a course of serious exercise in preparation to carry one. But I hadn’t truly known before Mrs. Buchanan’s glass bathtub.

No matter your age, you’ll still be a dream to me.” I think he meant this to be sweet, but all I could think was, my goodness, I’d still be a dream at that point? I wouldn’t be a fulfillment yet? That sounds exhausting. Does he have any idea how tiring it is to be someone else’s dream?

“If you’re gay,” I said, “then why were you chasing Daisy?” He slipped the partly cut book onto the shelf. “Do I really have to draw you the whole picture?”

He’s everything I ever would have said I wanted, anything any girl would want. If a fairy godmother had asked me to make a list of all I’d like in a young man, he’s what she’d cook up. But I love him only as a friend, or as a sister loves a brother. It’s as though I had all the ingredients set out to make Eton mess, or Mrs. Sanderson’s tomato soup cake, but I couldn’t follow the recipe. The ingredients wouldn’t come together. When I realized I loved my friend Jordan, it was as though that kitchen, where before I couldn’t make a cake or a pavlova, turned into a land of sweets. The air burst

...more

“Fairy,” he said. “It’s a word I forgot to tell you about. It’s a word they use for boys like us. They mean it to be an insult, but I take it to mean there’s something magic about us and they know it.”

Learning this boy, touching him—it was as fractal as measuring a coastline. Within every corner and curve, there were countless more. Every feature of him I learned, I wanted to learn in greater depth and detail, every bay and channel and shoal.

It happened fast, Jay Gatsby becoming more legend than memory. The rich sons and daughters who drank champagne on his lawn whispered his name as though trying to grasp something, wondering if everything they remembered about the great Gatsby had been a dream.

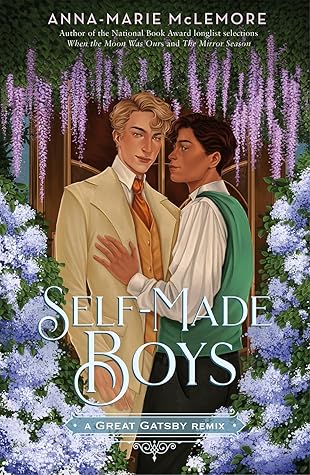

reimagining Jay and Nick as transgender casts them as self-made boys in perhaps the most literal sense.

The phrase self-made man has a complicated and often problematic history that seems to date back to the first half of the nineteenth century, but the concept was later redefined by Frederick Douglass in Self-Made Men: “Properly speaking, there are in the world no such men as self-made men. That term implies an individual independence of the past and present which can never exist.” Nick and Jay are making themselves as boys and men, but they can’t do it without each other and without their communities. As trans boys, we make ourselves, but we don’t do it alone. None of us makes ourselves alone.