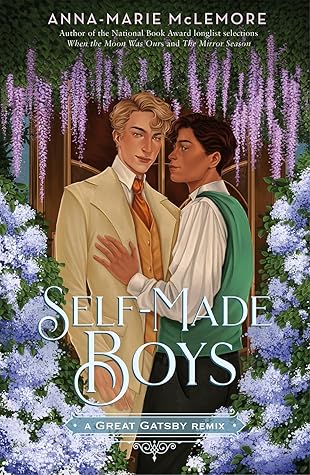

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 22 - September 26, 2022

Gatsby looked back at me how any boy in the world would want to be looked at—as though there was such infinite possibility in me, such infinite light, that I was one endless, longest day of the year.

everyone here had a generous air to them, like we’d all come in out of the rain together.

The music grew louder, and then half the group was dancing, the room shuddering with frantic joy.

He was close enough that I could smell his cologne, something green growing under rain, like wild clary. Alongside the dark wood shelves of his bedroom, I felt the dividing pull of something between lovesickness and homesickness. The green of that cologne and the deep wood called up Wisconsin trees.

He took hold of the lapels, shifting the seams on my shoulders. “You look marvelous.” I would have sworn to a priest that Gatsby’s smile pulled light in through the windows.

“I don’t think I should leave you alone tonight,” Gatsby said. “Do you want to stay with me?” “No,” I said. “I’m fine.” “Then I’ll stay here with you,” he said. I wanted to say yes to having another heartbeat in the cottage with me, and to that heartbeat being his. And in a locked cabinet deeper within me, I might have imagined the warmth of his body next to me, kissing him in the dark.

As they spun, they threw their heads back. Her honeyed hair and her rose skirt floated behind her. His enchanted laugh sounded distant filtered through the glass. Every few seconds they spun near enough to leave nothing between them and us, and his laugh was clear and close. Then they kept spinning, and he went away again, and his laugh sounded as far as another planet. That laugh was a lighthouse beam, illuminating me and then leaving me unseen in alternating seconds.

The flare had been lit in me. It was a dock light bursting, spilling its filaments everywhere. My cousin and Gatsby were holding the shimmer of their former lives between them, their dance-hall laughs caught in each other’s hair and within the glass of revolving doors.

“What do you mean?” I asked. “Mírame,” Jordan said. I went still, beginning with the blood at the center of my heart, then out to my fingertips. In that second of hearing Jordan’s Spanish, the sound flawless and familiar, I was so still that the gust off the ocean couldn’t move the strands of my hair.

I tried to acquaint myself with the idea that an insult could be reclaimed into something softer, something fit for the space inside a heart or between sheets.

Gardeners carried in wooden crates filled with dark earth and topped with bulb flowers. By afternoon’s end, a river of grape hyacinth deeper than the blue of the bay ran through the grounds. The indigo flowers clustered so closely and densely, the ocean breeze rippling the stalks, that a few drinks might have made them seem like real water. Banks of daffodils shouldered either side. Islands of coral tulips and fields of hyacinths in every shade of pink broke up the expanses of grass.

To him, I was a good friend. But my heart now followed his the way his followed Daisy’s. She was the sun around which his being orbited, and I was his moon, shadowed and undetected.

We spent our nights in salt water. The moon turned the wet sand to silver, and we lay on it, looking up. The edge of the tide inched closer to our bare feet, the biggest waves lapping at our heels.

He’d already turned the compass of his heart. All it took was the moon beholding itself in the mirror of the sound to give him back his dreams.

Gatsby and I may have been nothing to men like Tom Buchanan, but men like that did not know we were as divine as the heavens. We were boys who had created ourselves. We had formed our own bodies, our own lives, from the ribs of the girls we were once assumed to be.

Some people wore their broken hearts with careful grace. I didn’t. The pieces of mine scraped against everything, and everyone could hear the grinding noise, even if they didn’t know what it was.

We kissed between rivers of blue hyacinths and gold daffodils. We kissed in the tide of the sound, still in our clothes, and the ocean dusted its reflected stars onto our skin. We carried salt and the moon on our bodies, sprinkling light and sea onto Gatsby’s sheets.

“Fairy,” he said. “It’s a word I forgot to tell you about. It’s a word they use for boys like us. They mean it to be an insult, but I take it to mean there’s something magic about us and they know it.”

Falling stars may have been spectacularly misnamed, but in this moment, I understood the impulse. The earth I was made of blazed like cosmic dust, lighting up brighter the faster I fell. Yes, there was inevitable space between all atoms. When my palm lay flush against his, when his lips pressed the perfect imprint of his mouth against my jawline, I knew there was still invisible distance between the charged particles of his body and mine. But I couldn’t feel that distance. We were electrons flying across each other’s orbits, throwing off quanta of light and energy.

Daisy walked down the pool steps and straight into the water. Her skirts floated up around her. She let the water lap over her head, and she was under, her hair billowing like her dress. The light went through the layers of fabric, so the water around her seemed to glow. She was again that diaphanous mermaid everyone had imagined when she’d fallen off a yacht. She went down, and then swam back toward the stairs. Soaked in salt water, Daisy Fabrega-Caraveo held the green star, a siren coming back from the sea.