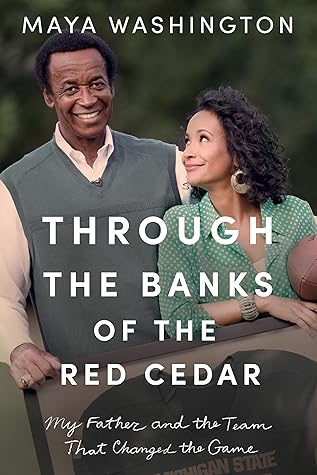

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 28, 2024 - January 18, 2025

My dad retired from 3M Corporation after a long career as a pioneer in diversity recruiting at the end of 2010, on the heels of being named one of the 50 Greatest Minnesota Vikings of all time. His business colleagues and even some of his famous former teammates, like Minnesota supreme court justice Alan Page (defensive tackle) and former UC Berkeley head football coach Joe Kapp (quarterback), gave their remarks at one of his two epic retirement parties.

My favorite moments were when countless mentees and protégés expressed the ways that my dad impacted their careers and lives: I got my first job, I got a PhD, and even, I met my future spouse—because of Gene Washington.

In January, my parents took us out of school on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. The day wasn’t a holiday yet, but it was a stance they took every year to acknowledge their Black children’s place in an all-white school district. We’d attend an early morning breakfast in the Black community where we’d sing the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and hear speeches from civic leaders.

I had white friends at school, and Black, brown, and other friends on the weekends.

On Sundays we’d attend Saint Joan of Arc Catholic Church in Minneapolis as a family. I spent Mass in the childcare room playing with kids of every race. It was a real hippie church led by Father Harvey Egan, who looked a lot like Willie Nelson to me. They had guitars and amps and projected the song lyrics on a giant screen next to the altar, which was positioned at one end of the school gymnasium. Often the Communion and closing hymns might be a secular song like “Shower the People” or “You’ve Got a Friend” performed in the style of Carole King and James Taylor. Our world was always diverse

...more

The thing I didn’t enjoy was when we’d stop in the rural towns where the all-white staff and patrons at the Dairy Queen or country diner would stare at me in a way that made the hair in my kitchen, at the nape of my Black neck, stand up.

I quickly ascribed this feeling of unspecified danger to white people who lived in rural Minnesota. I remember visiting white classmates who lived in rural areas and hearing their family members refer to Brazil nuts as nigger toes without flinching around me. By now I knew nigger was a bad word. That it meant a Black person. That it meant me.

I was mostly treated well by my teachers and classmates. Aside from the occasional insult or slur, I thrived in my school community. I truly enjoyed going to school every day, oblivious to how hard my parents’ generation fought for me to have the opportunity to get a public education equal to my white peers’.

It’s not like my dad’s college coach, Duffy Daugherty, just woke up one day and announced to his family on the way home from Mass on Easter Sunday that he was going to desegregate college football. From what I understand, there was no apparition or visit from an archangel or the Blessed Virgin. He didn’t look up in the rearview mirror at his adolescent son, Danny, in the back seat and say, How ’bout we get some Black players on the team? like something out of a Kevin Costner movie. It was so gradual that a lot of people missed it, forgot about it, or have no idea how significant Duffy

...more

it’s important to note that a series of events occurred almost 100 years before they were born that made a pipeline from Texas segregation to Michigan State possible. Their alma mater started as a land-grant institution called the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan in 1855. The simple college pretty much looked like a giant farm with a handful of buildings. It would be another hundred years before what is now known as Michigan State University could become a football powerhouse. Around the turn of the 20th century, the institution began enrolling women and a small handful of African

...more

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life: The honor of my race, family and self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part. —Jack

Jack either broke his collarbone or severely injured his shoulder during the second play in the game but wouldn’t take himself out. He persisted in grueling game play until the end of the third quarter when he went for a “roll block,” throwing himself onto an opposing player to make a tackle that landed him on his back. Once he was on the ground, three of Minnesota’s players stomped him mercilessly as the crowd at Northrop Field watched on. Later as he was carried off in a stretcher, the Gopher fans gave up “We’re sorry, Ames!” chants. Jack was taken to a local hospital and released hours

...more

John A. Hannah’s tenure as university president led to expansion efforts that transformed MSC into the major research institution (and member of the Big Ten Conference) known since 1964 as Michigan State University (MSU).

While MSC was willing to put its best players on the field regardless of race, the college observed a gentleman’s agreement when playing schools in the South. Northern schools would effectively bench Black players as a kind of neighborly way of upholding the white supremacy fancied by the southern way of life.

MSC sat their All American running back Horace Smith in 1946 against Mississippi State. The University of Kentucky first played against a black football player when they played MSC with Horace Smith starting. MSC lost.

John A. Hannah, the president of MSC, was appointed by president Dwight D. Eisenhower to the role of chairperson of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights from 1958 to 1969. The Commission on Civil Rights was created by the federal government as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, which sought to provide a continual appraisal of the status of civil rights in the United States, mainly investigating, documenting, and making recommendations.

the Commission on Civil Rights and the president of what became Michigan State University were collecting data and reporting on the conditions of Jim Crow just as my dad and Bubba Smith were emerging from its soil. In his tenure as chairperson, Hannah played a key role in the hearings that led to major legislation and court cases, including the Civil Rights Act of 1960, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

It helped that under Biggie Munn, the team had eight Black players and won the Rose Bowl in 1953.

One of his major power moves was the founding of the Coach of the Year Clinics, now sponsored by Nike, with University of Oklahoma coach Bud Wilkinson. The clinics traveled nationwide to provide training and development tools and networking opportunities for high school coaches. When the clinics traveled to the South, the Black coaches couldn’t attend workshops with the white coaches, so Duffy’s coaching staff, including defensive coaches Henry “Hank” Bullough and Vince Carillot, would lecture in separate rooms and sometimes in alternate venues to accommodate Black coaches.

Among the high school coaches that Duffy Daugherty courted was a Beaumont, Texas, football coach, Willie Ray Smith, the father of Charles Aaron “Bubba” Smith and Bubba’s two brothers, Willie Ray Smith Jr. and Tody Smith.

Bubba’s father fell into coaching in 1942 when the football and basketball coach at the all-Black Dunbar High School in Lufkin, Texas, was sent off to World War II. Coach Willie Ray Smith Sr. didn’t know a tackle from a halfback, but he needed a job. Most of the adult men in the area had been called to military service at the time. Coach Smith was shot in the leg trying to break up a heated argument between two brothers in Denton, Texas, back in 1934, so he couldn’t pass the physical requirements for military service.

The Washingtons were a fairly close-knit family and well liked in the community. They were active members of Zion Hill Baptist Church and kept the kids on a rather short leash. My grandfather was a deacon in the church, and my grandmother sang in the choir. They attended services before and after the regular morning services, followed by afternoon and evening services on Sunday. On weekdays my dad was bused to George Washington Carver High School in Baytown, Texas, because La Porte Independent School District didn’t provide a high school for Black students. Even though La Porte High School was

...more

My grandfather agreed to let my dad participate on the condition that the coaches—Johnny Peoples (football), Robert Strayhan (track), and Richard Lewis (baseball)—give him rides the long distance back to La Porte at the end of the day, since the school buses weren’t in service by the time practices let out. The terms of the deal also included transportation to and from games and meets.

It’s hard to pinpoint the time line in terms of when and how the Smiths told Duffy Daugherty about my dad. It’s likely the camaraderie began when Willie Ray Smith Sr. coached Bubba and my dad in a high school East-West All-Star Game in their junior or senior year. They developed a friendship, and when my dad heard that Bubba was planning to accept an offer at Michigan State, Coach Smith said he’d put in a “good word” to Duffy Daugherty in hopes they’d consider my dad as well. And he did.

It was a lot to deal with on top of the universal American adolescent struggle. Almost overnight, those same boys who once played baseball with me at the park in front of our house started calling me Fro and would routinely spit on the back of my head when they sat behind me in class or on the bus. The blond boy who gave me a ring and had asked me to “go with him” in fourth grade stopped talking to me altogether.

After Maya’s American History teacher showed Roots to her class, with no context. Maya instantly became the, “other”, among her classmates.

My mother was in the early years of a born-again Christian journey. The Catholic edition. She became active in a Catholic Charismatic Renewal community, who, like their Pentecostal brethren and sistren, would catch the Holy Ghost and pass out, speak in tongues, or both.

Their greatest tool in a noble fight against oppression was my dad’s insistence that You have to be twice as good at everything. You have to run faster, you have to work harder, and be the best at everything just to be seen as equal. They lived this mantra in every fiber of their beings.

Living with this paradox of late 20th-century psychology that says, “Be yourself” yet “Be perfect,” so white people will accept you and not accuse you of something you didn’t do, is among the many internal conflicts I’ve had to sort out my whole life. Perfectionism

I still make large sweeping gestures when I pick up an item and return it to its proper place on a store shelf, so the security cameras catch me not shoplifting. I always drive the speed limit, even on long open-highway road trips, because I’m terrified of being pulled over. In my experience, my brown skin in America means I can be treated like an object that’s out of its place.

Michigan State’s offensive line coach Cal Stoll stood on that very street, walked over the little driveway, crossed the ditch, and knocked on the door, meeting my dad and his parents, Henry and Alberta Washington, for a recruitment visit in early 1963. They’d never had a white person in their home before.

“Is all of this free?” my grandfather pressed. “Yes, Eugene will be on a scholarship. He’ll play football and his tuition, room, and board will be covered by the scholarship.” It was settled. MSU sent my dad a plane ticket to East Lansing and he was on his way. What he didn’t realize was that Duffy had run out of football scholarships, so the university took him on a track scholarship instead. This meant that he’d be required to run indoor and outdoor track and play football for Michigan State.

Joe Namath, who supposedly couldn’t meet the academic requirements at MSU.

When he arrived at the Kellogg Center, the campus hotel, he was taken aback by the opportunity to enter through the front door. “I’d never stayed in a hotel before. Everything was really different. I mean, I’d never gone anywhere in my life, really. And next thing you know? I’m in East Lansing,” he recalled as my crew and I captured an interview back in 2014. “What did you think of it?” I blurted, trying to imagine the magnitude of his experience. “I thought everything was nice. It was really nice. A big campus. I was interested in seeing where we’d have our classes. The opportunity to get an

...more

He’d never been in a restaurant, and he’d never seen or ordered off a menu before. He sat politely and observed the coaches and MSU personnel as they interacted with the young white waitress. She turned to my dad and asked, “What will you be having for breakfast?” Thinking quickly on his feet, he responded, “I’ll have what the coaches are having.”

Lansing, Michigan, still had some room to grow when it came to race relations. Housing was still segregated, and opportunities for Black residents in Michigan’s capital were limited in 1963.

On August 28, 1963, nearly 250,000 people gathered in Washington, DC, for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In East Lansing, the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream ushered in the beginning of the school year and my dad’s new life as an MSU Spartan. The Black players, especially those who’d left the segregated South, had an instant connection with one another. They didn’t discuss the details of what life was like for them under Jim Crow. They had a quiet understanding of what they’d all been up against and the stakes ahead for them as individuals and eventually members of the

...more

I never had the opportunity to thank Bubba Smith before he died for recommending my dad for his scholarship at Michigan State. Through that gesture, a world that was previously off-limits because of the color of his skin opened to my father. His life and the lives of many others were forever changed on the banks of the Red Cedar River in the 1960s.

The large class sizes and the nuances of interacting with white students were major adjustments for Black players who’d otherwise had no contact with white people before their time at Michigan State.

my dad always makes a point to mention the number of years he and my mother have been married in his public speeches. His marriage is a source of pride and accomplishment to him.

broadcast on local radio and television on September 13, 1962. I speak to you now in the moment of our greatest crisis since the War Between the States . . . I have said in every county in Mississippi that no school in our state will be integrated while I am your governor. I repeat to you tonight: no school in our state will be integrated while I am your governor. There is no case in history where the Caucasian race has survived social integration. We will not drink from the cup of genocide.

“The ’65 team and the tremendous defense, I think the greatest defense in college football history. They play Ohio State minus 22 yards rushing. Michigan? Minus 38 yards rushing. Notre Dame—minus 12 yards rushing. This wasn’t just another Notre Dame team. This was a Notre Dame team that was ranked number four in the country. Michigan State ranked number one in the country,” he said with a glint in his eye.

Michigan State was very much a living—albeit isolated—laboratory. If Duffy Daugherty, the wealthy whites in the East Lansing community, and their middle-class and blue-collar counterparts didn’t love Michigan State athletics as much as they did, this integration experiment could have ended badly—or worse, not existed at all. In many ways, my dad was protected by a cover of whiteness at the highest level with John A. Hannah as the university’s president, reporting directly to President Kennedy and later President Johnson, throughout his college years.

Being a Black face in a white space didn’t seem to affect my dad, because he was just happy he wasn’t in Texas. My dad was, and still is, a good-looking man. His strong limbs, smooth dark skin, and thousand-watt smile resulted in adoration from white girls, and likely white boys, who stared a little too long when he walked into a room. Still my dad was extremely reserved in the face of public attention.