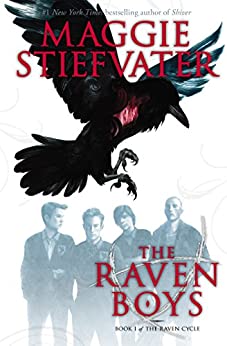

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Blue Sargent had forgotten how many times she’d been told that she would kill her true love.

If Blue was to kiss her true love, he would die.

“You’re Maura’s daughter,” Neeve said, and before Blue could answer, she added, “this is the year you’ll fall in love.”

and the parking lot full of cars that spoke German

Aglionby Academy was the number one reason Blue had developed her two rules: One, stay away from boys, because they were trouble. And two, stay away from Aglionby boys, because they were bastards.

Nothing to hear, nothing to see. No evidence of the dead except for their names written in the notebook in her hand.

“There are only two reasons a non-seer would see a spirit on St. Mark’s Eve, Blue. Either you’re his true love,” Neeve said, “or you killed him.”

As always, there was an all-American war hero look to him, coded in his tousled brown hair, his summer-narrowed hazel eyes, the straight nose that ancient Anglo-Saxons had graciously passed on to him. Everything about him suggested valor and power and a firm handshake.

There were two Ganseys: the one who lived inside his skin, and the one Gansey put on in the morning when he slid his wallet into the back pocket of his chinos.

Dick Gansey III hated to be told that he sounded like Dick Gansey II, but right then, he did.

From his father, Gansey had gotten a head for logic, an affection for research, and a trust fund the size of most state lotteries.

From their father, the Lynch brothers had gotten indefatigable egos, a decade of obscure Irish music instrument lessons, and the ability to box like they meant it.

Sometimes, Gansey felt like his life was made up of a dozen hours that he could never forget.

He wasn’t naive; he carried no illusions that he’d ever recover the Ronan Lynch he’d known before Niall died. But he didn’t want to lose the Ronan Lynch he had now.

Adam had once told Gansey, Rags to riches isn’t a story anyone wants to hear until after it’s done.

The poor are sad they’re poor, Adam had once mused, and turns out the rich are sad they’re rich.

Success meant nothing to Adam if he hadn’t done it for himself.

Robert Parrish was a big thing, colorless as August, grown from the dust that surrounded the trailers.

he still had that handsome glow. The glow that meant that not only had he never been poor, but his father hadn’t, nor his father’s father, nor his father’s father’s father. She couldn’t tell if he was actually tremendously good-looking or merely tremendously wealthy. Perhaps they were the same thing.

When Gansey was polite, it made him powerful. When Adam was polite, he was giving power away.

The approval of someone like him, who clearly cared for no one, seemed like it would be worth more.

Calla interrupted. “A secret killed your father and you know what it was.”

The raven boy?” “They’re all raven boys,” Blue said. Her mother shook her head. “No, he’s more raven than the others.”

Adam wouldn’t admit it to anyone, least of all Gansey, but he was tired. He was tired of squeezing homework in between his part-time jobs, of squeezing in sleep, squeezing in the hunt for Glendower. The jobs felt like so much wasted time: In five years, no one would care if he’d worked at a trailer factory. They’d only care if he’d graduated from Aglionby with perfect grades, or if he’d found Glendower, or if he was still alive.

He’d had to leave the boxes and the toothpaste on the conveyer belt, eyes hot with shamed tears that wouldn’t fall. He’d never wanted to be someone else so badly.

The journal and Gansey were clearly long-acquainted, and he wanted her to know. This is me. The real me.

Ronan said, “I’m always straight.” Adam replied, “Oh, man, that’s the biggest lie you’ve ever told.”

She recognized the strange happiness that came from loving something without knowing why you did, that strange happiness that was sometimes so big that it felt like sadness. It was the way she felt when she looked at the stars.

The boy in the Aglionby sweater leaned his forehead against Blue’s. She felt the pressure of his skin against hers, and suddenly she could smell mint. It’ll be okay, Gansey told the other Blue. She could tell that he was afraid. It’ll be okay.

this other Blue was crying because she loved Gansey. And that the reason Gansey touched her like that, his fingers so careful with her, was because he knew that her kiss could kill him. She could feel how badly the other Blue wanted to kiss him, even as she dreaded

Okay. I’m ready — Gansey’s voice caught, just a little. Blue, kiss me.

“I want you to know,” Adam whispered furiously, “I would never do that. It wasn’t real. I’d never do that to him.”

There was something very ancient about him just then, with the tree arched over him and his eyelids rendered colorless in the shadows.

She was right like Ronan had been right, like Adam had been right, like Noah had been right.

Gansey dead, dying, because of him. Blue looking at Adam, shocked. Ronan, crouched beside Gansey, his face miserable, snarling, Are you happy now, Adam? Is this what you wanted?

Noah had decided almost immediately that he would do anything for Blue, a fact that would’ve needled Adam if it had been anyone other than Noah.

Noah shrank up the side of the car, trying desperately not to touch Blue.

“You’re always cold, though, Noah,” she said. “I know,” he replied, bleak.

Blue tried not to look at Gansey’s boat shoes; she felt better about him as a person if she pretended he wasn’t wearing them.

He was wearing a teal polo shirt, and it seemed impossible that someone in a teal polo shirt could perish of anything other than heart disease at age eighty-six, possibly at a polo match.

Gansey, suddenly charming again, flipped a hand in the direction of her purple tunic dress. “Lead the way, Eggplant.”

“Thanks for coming, Jane,” Gansey said. Blue shot him a dirty look. “You’re welcome, Dick.” He looked pained. “Please don’t.”

“This is all down to you. Putting us on the line, finally. I could kiss you.”

“I heard a voice. It was a whisper. I won’t forget what it said. It said: ‘You will live because of Glendower. Someone else on the ley line is dying when they should not, and so you will live when you should not.’”

“And that’s enough to make you spend your life looking for Glendower?” Gansey replied, “Once Arthur knew the grail existed, how could he not look for it?”

They stared at each other over the body. Lightning lit the sides of their faces.

The face on the driver’s license was Noah’s.

“It’s Czerny, by the way. Zerny. Chair-knee. However

“Mine,” Noah said. As one, they spun back around. Noah stood in the doorway to his room.

Blue just kept thinking of the skull with its face smashed in, of Noah retching at the sight of the Mustang. Not throwing up. Just going through the actions of it, because he was dead.