More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

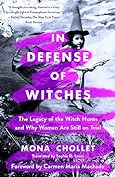

by

Mona Chollet

Read between

October 17 - October 23, 2024

“Many of Bruges’ inhabitants still bear these surnames and, before visiting the exhibition, they had no idea they could have an ancestor accused of witchcraft,” the museum’s director commented in the documentary Dans le sillage des sorcières de Bruegel. This was said with a smile, as if the fact of finding in your family tree an innocent woman murdered on grounds of delusional allegations were a cute little anecdote for dinner-party gossip. And it begs the question: which other mass crime, even one long-past, is it possible to speak of like this—with a smile?

The witch-hunts demonstrate, first, the stubborn tendency of all societies to find a scapegoat for their misfortunes and to lock themselves into a spiral of irrationality, cut off from all reasonable challenge, until the accumulation of hate-filled discourse and obsessional hostility justify a turn to physical violence, perceived as the legitimate defense of a beleaguered society. In Françoise d’Eaubonne’s words, the witch-hunts demonstrate our capacity to “trigger a massacre by following the logic of a lunatic.”8 The demonization of women as witches had much in common with anti-Semitism.

...more

“years of propaganda and terror sowed among men the seeds of a deep psychological alienation from women.”

“deeply embedded tendency in our society to hold women ultimately responsible for the violence committed against them.”

“When for ‘witches’ we read ‘women,’ we gain fuller comprehension of the cruelties inflicted by the church upon this portion of humanity.”

Do something once, it’s an experiment. Do it twice, and it’s a tradition.)

The witch appears at nightfall, just when everything seems to be lost. It is she who can uncover reserves of fresh hope amid the depths of despair.

capitalism is always engaged in selling back to us in product form all that it has first destroyed.

But capitalism also entailed the systematic plundering of natural resources and the establishment of a new conception of knowledge. The emerging new science was arrogant and imbued with contempt for femininity, which was associated with irrationality, sentimentality and hysteria, as well as with a natural world requiring domination (chapter 4). Modern medicine, in particular, was built on this model, and the witch-hunts enabled the official doctors of the period to eliminate competition from female healers—despite their being broadly more competent than the doctors.

I believe that magic is art, and that art … is literally magic. Art is, like magic, the science of manipulating symbols, words or images, to achieve changes in consciousness … Indeed, to cast a spell is simply to spell, to manipulate words, to change people’s consciousness, and this is why I believe that an artist or writer is the closest thing in the contemporary world to a shaman.

To try to dig out, from among the strata of accumulated images and discourses, what we take to be immutable truths, to shine a light on the arbitrary and contingent nature of the views to which we are unwittingly in thrall, and to replace them with others that allow us to live fully realized lives, that surround us in positive feedback: this is a kind of witchcraft I would be happy to practice for the rest of my life.

Nothing in the way most girls are educated encourages them to believe in their own strength and abilities, nor to cultivate and value their independence. They are taught not only to consider partnership and family the foundations of their personal achievements, but also to look on themselves as delicate and helpless, and to seek emotional security at all costs, such that their admiration for intrepid female adventurers remains purely notional and without impact on their own lives.

Boys are encouraged to map out their adult trajectory in the most adventurous manner possible. Conquering the world all alone is the most romantic path possible for a guy, and he can only pray that some lady doesn’t slow him down along the way, thereby ruining everything. But for women, the romance of forging out into the world is painted as pathetic and dreary if there’s no dude there. […] And Jesus, does it take hard work to reinvent the world outside those narrow conventions!

Damned clever, I thought, how men had made life so intolerable for single women that most would gladly embrace even bad marriages instead,

“The dictionary defines ‘adventurer’ as ‘a person who has, enjoys or seeks adventures,’ but ‘adventuress’ is ‘a woman who uses unscrupulous means in order to gain wealth or social position,’” Gloria Steinem points out.34

And they are creative women, who tend to read a lot and lead a rich life of the mind: “They live beyond the range of the male gaze, beyond that of most others, for their solitude is populated with works of art and with people, living and dead, dear as well as unknown, encounters with whom—whether in flesh and blood or in thought, through their oeuvres—form the foundations to the women’s sense of identity.”40 These women consider themselves individuals, not representatives of female types. Far from the miserable isolation that prejudice associates with women living alone, the ongoing shaping of

...more

“When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil.” Men, it seems, experience the merest breeze of equality as something like a catastrophic hurricane—there’s a similar exaggeration involved when majority groups feel under attack and consider themselves practically overwhelmed as soon as victims of racism show the least sign of standing up for themselves. Apart from resistance to renouncing their privilege (whether as men or as white people), this reaction displays the inability of the dominant to comprehend the experience of the dominated, but perhaps also, despite their indignant protestations of

...more

“instead of being rejected, the choice of a life alone is restored to its true status: that of a victory over multiple pressures that act upon the individual from the moment of her birth and condition a large number of her actions, ‘a pitched battle against the archetypes we carry within us, the conventions, the constant and ever-renewed social pressure.’”55 Only in this space do we suddenly discover other stories and other points of view, such as this one, from the Revue d’en face of June 1979: “Slow blossoming of desires, repossession of one’s body, of one’s bed, of space and time. An

...more

The whole power question comes down to separating people from what they can do. There is no power issue if people are self-sufficient. For me, the history of witchcraft could equally be called the history of independence.

Contrary to what today’s “backlash” would have us believe, women’s autonomy does not entail a severing of connections, but rather the opportunity to form bonds that do not infringe on our integrity or our freedom of choice, bonds that promote our personal development instead of blocking it—whatever lifestyle we choose, whether solo or in a partnership, with or without children. As Pam Grossman writes, “the Witch is arguably the only female archetype that has power on its own terms. She is not defined by anyone else. Wife, sister, mother, virgin, whore—these archetypes draw meaning based on

...more

women are positioned in such a way that their own identity is constantly at risk of being muddled with others,’ of atrophying, of being swallowed up altogether. They are prevented from living and fashioning their own lives, for the sake of representing an imagined quintessence of femininity.

Women are often told that blurring into the lives of the others is the right way to mother,

This reflex recalls the “conservation of energy” theory, developed by doctors in the nineteenth century, in which the human body’s organs and functions were thought to be in competition for the limited amount of energy circulating among them. From that point on, knowing their lives’ ultimate goal to be reproduction, women were obliged to “concentrate their physical energy internally, toward the womb,” as Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English explain.83 When pregnant, they were expected to remain horizontal for most of the day and avoid all other activity, especially anything intellectual:

...more

At work, too, we run the risk of “dissolving” away. The same subjection, the same reduction to stereotype also occurs here. The oppression of female medical workers—whether lay healers or officially recognized practitioners—and the establishment of a male monopoly in medicine, which happened in Europe during the Renaissance and in the United States toward the end of the nineteenth century, provides a perfect illustration of this. When women were allowed to return to the medical profession, it was as nurses; that is, in the subordinate position of assistants to the Great Men of Science, a

...more

In the 1960s, in the Éditions Nathan Encyclopédie de la femme (“Encyclopedia of Woman”), Monsarrat, a female doctor, was still describing girls’ education in these terms: It must be done in the most altruistic way. A woman’s role in life is to give everything to those around her—comfort, joy, beauty—while keeping a smile on her face, without making herself out to be a martyr, without ill humor, without visible fatigue. It’s a major task; we must lead every daughter toward this happy, lifelong renunciation. From her very first year, a girl must know how to share her toys and sweets

...more

Self-sacrifice remains the only fate imaginable for women. More precisely, it is a self-sacrifice that operates by way of abandoning one’s own creative potential rather than by its realization. Fortunately, we can also nurture those around us, whether they are from our innermost or wider circle, by developing our own particular strengths and giving free rein to our personal aspirations. This may even be the only form of self-sacrifice that we should seek to achieve, sharing out as best we can the portion of irreducible sacrifice that is inevitable, if there is some. Meanwhile, women’s

...more

Nevertheless, we are given them again and again.” She notes, “The idea that a life should seek meaning seldom emerges; not only are the standard activities [of marriage and children] assumed to be inherently meaningful, they are treated as the only meaningful options.”55 Solnit deplores the herd mentality that locks so many people into lives that conform entirely to social prescription and yet “are still miserable.” She reminds us, “There are so many things to love besides one’s own offspring, so many things that need love, so much other work love has to do in the world.

“women who create things other than children are still considered dangerous by many.”89 And best beware: even being Virginia Woolf cannot exonerate you for not being a mother.

the turbulence of the new social and psychoanalytical ideas of the 1970s did, somehow, lead to the astonishing injunction: ‘Do as you wish but do become parents.’” Women are particularly vulnerable to this paradoxical “injunction to want a child.” And they are all the more sensitive to it because, as one (voluntarily childless) woman remarked to Debest, they have a tendency “not to distinguish between what they want and what is asked of them.

on encountering voluntarily childless women, people still regularly threaten, “You’ll regret it one day!” They are betraying some very weird thinking. Can we force ourselves to do something we haven’t the least wish to do solely in order to head off a hypothetical regret hovering in the distant future? Such an argument ties these women right back into the system they are trying to escape, the unbreakable cycle of anticipation which is induced by a child’s presence and through which hopes of guaranteeing the future can eat up the present: take out a loan, work yourself to death, fret about the

...more

Women know how very difficult it is not to find ourselves, at least occasionally, systematically wanting what we do not have, and so not knowing very well where we stand.

Through these mothers’ experiences, Donath invites us not only to conclude that society should be making motherhood less difficult, but also that the expectation laid on women to become mothers is overdue a rewrite. Some women’s regret “indicates that there are other roads that society forbids women from taking, by a priori erasing alternative paths, such as nonmotherhood.” If we were to restore these forbidden paths, it is not guaranteed that the sky would fall on our heads. Perhaps we might even avoid many tragedies, much pointless suffering and much wasted energy. And we might see the

...more

can you make a good start in life if you are being told at the same time how terrible the finish is?

A man who is not interested in give and take between equals will prefer to turn to someone younger. He is more likely to find unconditional admiration from such an audience, and that’s more flattering than the gaze of the woman who knows him intimately, having lived with him for ten, fifteen or twenty years, even if she still loves him.

More broadly, what seems most problematic about women’s aging is their experience. This is what led so many old women to the pyres: “Spellcraft was an art. [Witches] had had to work at their lessons, to learn their knowledge, to gain experience: older women therefore naturally appeared more suspect than younger ones,” Guy Bechtel explains.71 Disney classics such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Sleeping Beauty “depict generational clashes between old witches and young beauties, pegging a woman’s worth on fertility and youth—never hard-won wisdom,

The disqualification of women’s experience represents an immense loss to and mutilation of our collective knowledge. Urging women to change as little as possible and censoring the signs of their maturing means locking them into a debilitating schema. A moment’s thought reveals the insane idealization entailed by our cult of youthfulness.

Older women’s sexuality also gave rise to particular fears around the time of the witch-hunts. No longer having the formal right to a sex life—since they could no longer have children and were, in many cases, widowed—yet experienced and still interested in sex, these women appeared as immoral and threatening forces in the social order. They were assumed to be bitter—for they had lost the respected status that went with the role of the mother—and envious of younger women. In the fifteenth century, as Lynn Botelho writes, a direct connection is established of “post-menopausal women with witches

...more

The witch, symbol of the violence of nature, raised storms, caused illness, destroyed crops, obstructed generation and killed infants. Disorderly women, like chaotic nature, needed to be controlled.”29 Once curbed and domesticated, both women and nature could be reduced to their decorative function, to become “psychological and recreational resources for the harried entrepreneur-husband.”

To a surprising degree, healthcare today still focuses on aspects of the science that were adopted during the witch-hunts: the spirit of aggressive domination and the hatred of women; belief in the omnipotence of science and of those who exercise it, but also in the separation of body and mind, and in a cold rationalism, shorn of all emotion.

Men’s stranglehold on the profession is far from a broadly abstract force, either. The world of healthcare—especially when it comes to gynecology and reproductive rights—seems keen to exercise ongoing control over women’s bodies and to ensure its own unlimited access to them. As if in never-ending reiteration of the joint project of taming nature and women, it seems these bodies must always be reduced to passivity, to ensure their obedience.

Having so long considered women to be naturally weak, sick and impaired—in the nineteenth century, some upper-middle-class women were regularly known as chronic invalids and, as such, were enjoined to remain in bed, until they went crazy with boredom—the healthcare system now seems to have changed its mind. These days, it suspects all women’s ailments of being “psychosomatic.” In short, women have gone from being “physically sick” to being “mentally ill.”

We may think regretfully of what Western medicine could have been today had that power grab—from the female healers, from women in general, and in opposition to all the values associated with them—not happened. Driven out of the medical profession, as we have seen, women were first allowed to return as nurses. As Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English observe, the nurse is an idealized woman—gentle, maternal, devoted—just as the doctor is an idealized man, haloed with the prestige of science; romance novelists are never wrong about these things. In his skilled hands lie the diagnostic

...more

“Healing, in its fullest sense, consists of both curing and caring, doctoring and nursing. The old lay healers of an earlier time had combined both functions, and were valued for both.”

Despite their parallel activity as sorceresses, about which we may be skeptical, and much more than the era’s official doctors, the female healers targeted by the witch-hunts were already working within the parameters of the rational; indeed, they are characterized by Ehrenreich and English as “safer and more effective” than the “regular” doctors.

In other words, the daring and foresight, the refusal to rely on old methods and the rejection of old superstitions didn’t necessarily come from the quarter we tend to expect. As early as 1893, Matilda Joslyn Gage was explaining, “we have abundant proof that the so-called ‘witch’ was among the most profoundly scientific persons of the age.”104 Associating witches with the Devil indicated that they had reached beyond the realm to which men had tried to confine them, and were now impinging on male privileges.

“Death by torture was the method of the Church for the repression of woman’s intellect, knowledge being held as evil and dangerous in her hands.”

If we examine this question more closely, there is something childish about the highly implausible claim to a rationality that is immaterial, pure, transparent and objective—childish and deeply fearful. Faced with a character who appears impervious to doubt and sure of himself, his knowledge and his superiority—whether he’s a doctor, a scholar, an intellectual or a barfly—it can be hard to remember that this stance may cloak a fundamental insecurity. And yet, this hypothesis is worth considering, as Mare Kandre implies in The Woman and Dr. Dreuf, in which she flushes out the terrified little

...more

“The movement that tried to kill the witches is also, unwittingly of course, that which paved the way, later on, for the lives and thought of Montesquieu, Voltaire and Kant.” In conclusion, he gives his blessing to a logic that he sums up with the maxim: “Killing the women of the past to create the men of the future.”115 And, in doing so, Bechtel shows, once again, that historians of the witch-hunts are themselves products of the world that hunted the witches, and that they remain locked inside the frame of reference that the witch-hunts created.

During the witchcraft period the minds of people were trained in a single direction. The chief lesson of the church that betrayal of friends was necessary to one’s own salvation created an intense selfishness. All humanitarian feeling was lost in the effort to secure heaven at the expense of others, even those most closely bound by ties of nature and affection. Mercy, tenderness, compassion were all obliterated. Truthfulness escaped from the Christian world; fear, sorrow and cruelty reigned pre-eminent. […] Contempt and hatred of women was inculcated with greater intensity; love of power and

...more