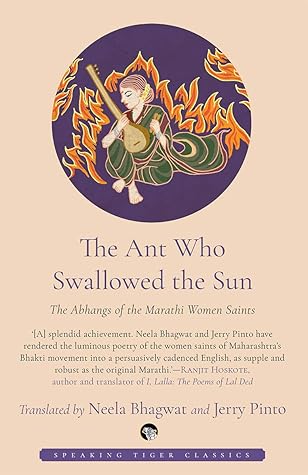

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Where Neela had composed the poem musically speaking, she would sing it to me so that I got a sense of what it could mean, what its underlying rasa was.

If one believes in God and one believes in religion, then surely both concepts are too large to be owned? And if one believes in God and one believes in religion, surely both concepts are too large to be damaged in any way by comment?

think the Bhakti poets—from Andal and Namdev to Kabir and Meerabai—would not understand either. They did not work this way. Their songs were invitations to love, to oneness, to liberation, to breaking away from categories like ‘me’ and ‘mine’ and ‘you’ and ‘yours’. They offer advice which is often imperious but it comes out of a sense of urgency. They are saintly in their love of God but they are not particularly kind; in many poems, they heap abuse upon the non-believer. They often sound contemporary and modern but they are of their time and any attempt to make them something else would be to

...more

gave myself permission to dislike her gendering of the child. Just as Neela and I gave ourselves permission to choose the poems we responded to, the ones that we felt we could translate.

might be a metaphor of surrender chosen because that was as much of Him as they could see from outside the temple. When they talk of eating with Him or feeding Him, it is because this would be to break the laws of caste that had a stranglehold on them.

His love was a strange thing—but which love is not?—for it seemed to have the power to heal and wound simultaneously. His name was enough. The power of song was enough. The collective celebration was enough. You did not need Sanskrit or shlokas; God would come to you and eat what you served Him and belch His love all over you.

So I am apologizing, as many of these women felt the need to apologize for their inadequacies when confronted with the divine.

Neela says in her introduction that women are the adi-dalits, the original caste that was broken and oppressed and silenced. Once again this has

been proved true.

He used the ovi—the three-and-a-half line form that women in Maharashtra devised to help pass the time as they worked their grinding stones to make flour.

Nivritti, Dnyandev, Sopan, Muktabai Eknath, Namdev, Tukaram.

It may be noted that Muktabai’s is the only female name in that litany of saint-poets.

Moreover in the last fifty years or so, the feminist movement has brought us to the realization that women are the ‘adi-dalits’, the original dalits, those who own no land, wield no power and have no say in the way their worlds are shaped. In Bahinabai’s time, as now, women had to mount a constant fight to secure their rights and to hold them. They had to exercise eternal vigilance. Soyarabai, Nirmala, Janabai, Kanhopatra, Bhaagu, Vatsara, Bahinabai, all lived in circumstances that we would consider difficult, if not downright pitiable. But the Bhakti tradition with its direct approach to God,

...more

Life might have been poor, miserable and full of back-breaking labour, but Bhakti offered a way out.

This is available to everyone but you must strive to understand and internalize it.

That it takes a younger sister to explain the workings of the world to an elder brother may be taken as a sign of her wisdom, her emotional balance and her awareness of social reality. She looks out at the world and may not like what she sees but she remains positive through it all.

Chokhamela says of menstruation, which was seen as ritually impure: Panchahi bhootaancha ekachi ekaachi vitaal Avaghaachi mel jagi naande. The five elements mingle in this pollution Which is the source of creation in the world.

How are we to understand this surrender? As a feminist, how do I understand this surrender to a male force? (Then the next question: Is it a male force? But that is a debate for another time.) For me, Nirmala’s challenge is the challenge of accepting consequences. You must choose the path you tread and you must accept the consequences of that choice.

Kanhopatra considers Vitthala her husband. There is a parallel here with Sant Meerabai of the 15th century. Meerabai tells us of the strong love she had for Krishna and the frustrations of living an earthly life and trying to contend with an earthly husband. Eventually she liberates herself from the constraints of the caste system and takes the cobbler Rohidas as her guru. She leaves the palace and the royal family; she joins the legion of Krishna bhakts who include men and women of all walks of life and all strata of society. Kanhopatra curses her profession as lowly; she wants to be pure and

...more

How is it that God who can come in the night to repair the house of a devotee allows her to be abandoned as one without protection? The Lord hears and loses His appetite. He withdraws His hand from the food and asks that Jani be brought to Him. He offers her the food He has left, thus forging a bond with her, a bond that the other Gods would love to have.

When this fractured state becomes unbearable, one remembers the unifying power of the Bhakti movement.

Progress does not necessarily have to be at the cost of humanism. There are many miracles that are recounted as part of the

Classical khayal music is deeply influenced by the Sufi and Bhakti sects; one discovers these instances as one sings these abhangs.

Just as we settled down to grieving, She announced that she was leaving.

Muktabai says: A sign of liberation? Look for a being bright with compassion.

With no beginning and no end, Are you free to go with the flow?

Until you acknowledge the temple within How can you experience compassion?

The rich and the poor struggle between being and freeing. Neither sees what is tangibly there. This cloud of delusion, this house of doubt: Welcome to Maya. Muktai offers this milk of instruction: One God; every possible emotional state

Our need for form? That old habit: Maya.

She’s seen that it’s all one. All of it.

Those who aspire to be saints, Must bear the world’s spite without complaints.

Yes, the world seems ablaze. The saint is water on such days.

Soyara says: I find it odd Not one among them remembers God.

Soyara says: I’m drowning. Pull me out.

Who is being seen? Who is seeing?

You say some bodies are untouchable. Tell me what you say of the soul.

menstrual blood makes me impure, Tell me who was not born of that blood.

That’s why I praise only Panduranga, Who lives in every body, pure, impure.

‘Mine, mine,’ you say, snarled up in Maya’s net The mirage has you in thrall and yet You can free yourself, if you remember your self.

Soyara says: Vittho, this is just not right.

Kiti

The love of others touches You. Why do You refuse mine?

don’t care if You bear a grudge. Soyara says: I’m here. I won’t budge.

Soyara says: I find it odd; Those who know nothing, speak most of God.

Trapped in dreams of children and gold dust, Why can’t they free themselves from lust? Soyara wonders: Who will spring this trap? Life after life, must they take this crap?

No thought of Godhead crosses His mind When He helps her pound and grind.

Jani says: I have become Your whore, Keshava. I come now to wreck Your home.

No sin left no self left.

Janabai’s warning? He possesses you completely.

Can the water spurn the fish? Can a mother reject her son? Jani says: I give up. Save me if You wish.