More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

One of the first clues came while I was tapping into the messages that the trees were relaying back and forth through a cryptic underground fungal network. When I followed the clandestine path of the conversations, I learned that this network is pervasive through the entire forest floor, connecting all the trees in a constellation of tree hubs and fungal links.

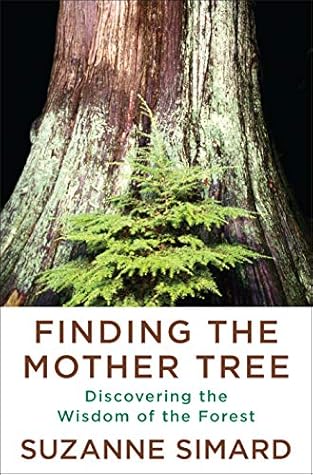

A crude map revealed, stunningly, that the biggest, oldest timbers are the sources of fungal connections to regenerating seedlings. Not only that, they connect to all neighbors, young and old, serving as the linchpins for a jungle of threads and synapses and nodes.

The old trees nurture the young ones and provide them food and water just as we do with our own children. It is enough to make one pause, take a deep breath, and contemplate the social nature of the forest and how this is critical for evolution. The fungal network appears to wire the trees for fitness. And more. These old trees are mothering their children.

This is not a book about how we can save the trees. This is a book about how the trees might save us.

Scientists had recently figured out that mycorrhizal fungi helped food crops grow because the fungi could reach scarce minerals, nutrients, and water that the plants couldn’t. Adding fertilizers full of minerals and nutrients, or providing irrigation, artificially took care of things, causing the fungi to disappear.

inconsistent results made it far easier to pour on fertilizer than cultivate healthy mycorrhizas. I chuckled at the humanness of this—we are always looking for the quick fix.

foresters ignored the mycorrhizas, or—worse—killed them with fertilizer and irrigation in the seedling nursery, and focused only on those fungi that damaged or killed big trees, the pathogens. Those parasitic fungal species that infected roots and stems, damaged wood, and sometimes killed trees. The pathogenic fungi could, in short order, cost the industry a big whack of money.

Burnley liked this

professors in forestry school also taught us about saprophytes, the fungal species that decompose dead stuff, because they were obviously crucial to the cycling of nutrients. Without the saprophytes, the forest would choke from accumulated detritus, as our towns and cities would from garbage.

The mycorrhizal symbiosis was credited with the migration of ancient plants from the ocean to land about 450 to 700 million years ago. Colonization of plants with fungi enabled them to acquire sufficient nutrients from the barren, inhospitable rock to gain a toehold and survive on land. These authors were suggesting that cooperation was essential to evolution.

the fungus missing from the soil was the key to my dying seedlings. The industry had figured out how to grow seedlings in the nursery and plant them but totally missed that the collaborative relationships, the mycorrhizas, needed nurturing as well.

Old-growth forest with ancient western red cedar Mother Trees in the overstory and western hemlock, amabilis fir, huckleberries, and salmonberry in the understory. Western red cedar is known as the tree of life to the Aboriginal people of the West Coast of North America, for whom it is of great spiritual, cultural, medicinal, and ecological significance.