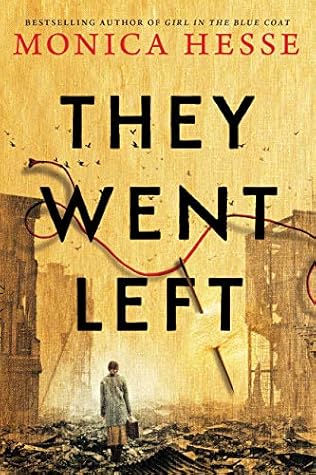

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“When I find you again, we will fill our alphabet.

But none of the nothing-girls were well enough then. So we don’t have a protocol yet for what to do when one of us leaves. We have no addresses to exchange. We have nothing. We weigh nothing, we feel nothing, we existed on nothing, for years.

“It’s over now,” the soldiers said to us in February. It wasn’t over, not officially,

“It’s really over now,” the nurses told us in May, spoon-feeding us sugar water and porridge.

Sometimes it’s not that I have trouble remembering things, it’s that I have trouble forgetting.

Because everyone else: Papa, Mama, Baba Rose, beautiful Aunt Maja—all of them, all of them, as the population of Sosnowiec was devastated—they went left.

But Birkenau, the first camp, was barely twenty-five kilometers from my town.

We had no idea how little the city loved us back.

When we first moved into the ghetto, Abek got lost. He wandered off and was missing for hours; he didn’t know the new address. My mother loved him, of course; she loved us both. But when Abek was born, she was sick in her room for a long time—fragile, my father and grandparents said. It was hard on her body. I took care of him when he was small. And on the day he got lost, when he was returned hours later by a helpful passerby who had wandered the streets until Abek recognized our building, it was me he ran to, crying.

The story of our family, told in the alphabet:

I didn’t think any of you would be back. That’s what Mrs. Wójcik said. But she didn’t say it with gratitude in her voice. She didn’t mean it like, I am so relieved to see you. Her voice didn’t sound happy. Her voice sounded disappointed. What she meant was, I thought they killed you all.

The train station at Birkenau is my black ice, a sleeping black monster guarding the door of my memory. Nudge it too hard and it will wake.

is Judenrein.”

my heart has continued beating even while the hearts of almost everyone else I ever met have stopped beating, and that is why my heart hurts.

In my childhood bedroom, where I have not slept since before my family was murdered and my country was broken, I unroll the bed mat brought to me by a Russian soldier.

This young soldier said he could manage something, but it would be a big favor, requiring payment. I put my hand down his pants; I was very pretty then. Three minutes later, he agreed.

my body remembers.

We pass a man painting a sign: We’re still a long distance from Munich. But the notice is not only in German, it’s also in Russian, French, and English.

It’s a patchwork, is what she’s saying. It’s the continent trying to sew itself together using a blend of every kind of stitch and knit available.

Nobody cares if Josef got in a fight with Rudolf, because he’s a collaborator. He volunteered his house to the Gestapo.

stammer. “Sometimes timelines get mixed up in my head. Or I’ll think I remember something that didn’t happen, or I’ll forget something that did.

“Not all people want to be found.”

Since the moment I woke up in the hospital, since the moment the war ended and I began trying to piece my brain back together, I have really been asking only one question. “Josef.” My voice is barely above a whisper. “What if my brother is dead?”

and they all know what to do right now because their faith is the same language.

I forgot that pleasure could feel this strong. After years of feeling nothing but perpetual, insistent pain, my body had begun to feel like an instrument of it. Like it was built to withstand things rather than experience them.

They didn’t send my father to the left when we got to Birkenau. My father was already dead.

I do not want to think about how he might not be my brother.

“Were you in the German Army? Just answer my question.”

It still took away pieces of my soul with every passing second. It was still, I think, a mercy.

Anti-Semitism was still rampant; the war didn’t end people’s prejudice.