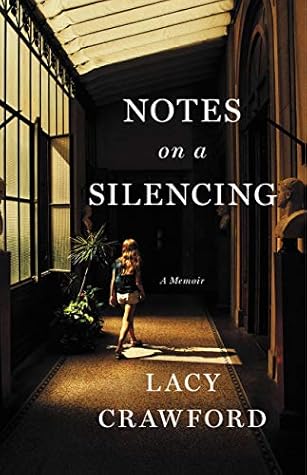

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In other words: to believe in the perfect victim is to believe in no victim at all.

Besides immorality, the salient feature of entitlement, I think, is the total failure of imagination.

It’s a curious thing how children are wired to ask for help when hurt or frightened—Ouch! Help me!—but shame turns this inside out: I can survive this as long as nobody else ever knows. As though secrecy itself performed some cauterizing function, which, of course, when it comes to the matter of self-delusion, it does. I couldn’t talk about what had happened without having to let myself think about what had happened. The secret served me.

There is a contemporary inquiry into shame that suggests that shame is not as deeply rooted in guilt as in power.

“Sure. You’re devastated. They stole your self-respect and ruined your sense of boundaries. It’s natural to take some time to get those things back.”

I learned that while the fallen woman may keep her unloved door plain and her drapes drawn, her circle small and her fire low—if she’s wise, I suppose, she will—the path to her back stoop will be well-traveled. I guarantee it.

It’s so simple, what happened at St. Paul’s. It happens all the time. First, they refused to believe me. Then they shamed me. Then they silenced me. On balance, if this is a girl’s trajectory from dignity to disappearance, I say it is better to be a slut than to be silent. I believe, in fact, that the slur slut carries within it, Trojan-horse style, silence as its true intent. That the opposite of slut is not virtue but voice.