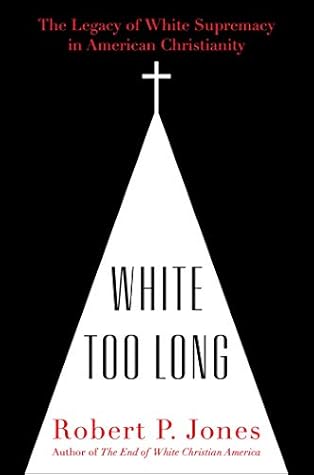

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 27 - October 10, 2020

The Christian denomination in which I grew up was founded on the proposition that chattel slavery could flourish alongside the gospel of Jesus Christ. Its founders believed this arrangement was not just possible but also divinely mandated.

it is time—indeed, well beyond time—for white Christians in the United States to reckon with the racism of our past and the willful amnesia of our present. Underneath the glossy, self-congratulatory histories that white Christian churches have written about themselves is a thinly veiled, deeply troubling reality. White Christian churches have not just been complacent; they have not only been complicit; rather, as the dominant cultural power in America, they have been responsible for constructing and sustaining a project to protect white supremacy and resist black equality. This project has

...more

American Christianity’s theological core has been thoroughly structured by an interest in protecting white supremacy. While it may seem obvious to mainstream white Christians today that slavery, segregation, and overt declarations of white supremacy are antithetical to the teachings of Jesus, such a conviction is, in fact, recent and only partially conscious for most white American Christians and churches. The unsettling truth is that, for nearly all of American history, the Jesus conjured by most white congregations was not merely indifferent to the status quo of racial inequality; he

...more

After centuries of complicity, the norms of white supremacy have become deeply and broadly integrated into white Christian identity, operating far below the level of consciousness. To many well-meaning white Christians today—evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant, and Catholic—Christianity and a cultural norm of white supremacy now often feel indistinguishable, with an attack on the latter triggering a full defense of the former.

As the Democratic Party came to be identified as the party of civil rights, white Christians increasingly moved to the Republican Party—a migration that political scientists have dubbed “the great white switch.”11 Beginning with 1980 and in every national presidential election since, the voting patterns of religious Americans can be accurately described this way: majorities of white Christians—including not just evangelicals but also mainliners and Catholics—vote for Republican candidates, while majorities of all other religious groups vote for Democratic candidates.

While much has been made of the strong support of white evangelical Protestants for Trump (81 percent, according to the exit polls in 2016), a Pew Research Center postelection analysis based on validated voters found that strong majorities of white Catholics (64 percent) and white mainline Protestants (57 percent) also cast their votes for Trump. By contrast, fully 96 percent of African American Protestants and 62 percent of white religiously unaffiliated voters cast their votes for the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton.18

most white Christians continue to operate as if the theological world they have inherited and continue to sustain is somehow “free of, uninformed, and unshaped by” the presence of African Americans. The power of this mythology of pure, isolated white Christian theology can be seen in the fact that it persists even in the face of glaring historical facts to the contrary.

White Christians, and even my own childhood home denomination, are gradually beginning to face the bare fact that white supremacy has played a role in shaping American Christianity. But they have been too quick to see laments and apologies as the end, rather than the beginning, of a process. They also remain full of contradictions and too quickly avert their gaze when the weighty implications of history require concrete, sustained action in the present.

A moment of reckoning is upon us, and it’s time that we white Christians do better, to see what is plainly in front of us and to wrestle with the unsettling implications. What if the racist views of historical “titans of the faith” infected the entire theological project contemporary white Christians have inherited from top to bottom? If white supremacy was an unquestionable cultural assumption in America, what does it mean that Christian doctrines by necessity had to develop in ways that were compatible with that worldview? What if, for example, Christian conceptions of marriage and family,

...more

White Christian selectivity harnessed the Bible in service of maintaining the current status quo, which, conveniently, was structured to maintain white supremacy.

When white supremacy was still safely ensconced in the wider culture, white evangelicals argued that the Bible mandated a privatized religion. This was a powerful way of delegitimizing the work of black ministers working for black equality. But as these forces gained power, white evangelicals discovered a biblical mandate for political organizing and resistance.

There is stronger evidence that it is the other way around: that white Christians’ cultural worldview, with an unacknowledged white supremacy sleeping at its core, has been read back into the Bible. And if this is true, a deeper interrogation of our entire theological worldview, including our understanding and use of the Bible and even core theological doctrines of a personal relationship with Jesus, is in order. Until we find the courage to face these appalling errors of our recent past, white Christians should probably avoid any further proclamations about what “the Bible teaches” or what

...more

Placed in historical context, the spikes in monument construction are clearly correlated with periods of white reassertions of political and cultural power.

Ultimately, the construction of a new foundation will require white Americans to do something we have never been willing to do: reanimate our own histories and confront a violent and unflattering past.

On the one hand, white Christians explicitly profess warm attitudes toward African Americans. At the same time, however, they strongly support the continued existence of Confederate monuments to white supremacy and consistently deny the existence not only of historical structural barriers to black achievement but also of existing structural injustices in the way African Americans are treated by police, the courts, workplaces, and other institutions in the country. And, notably, Christian affiliation remains a powerful differentiator among whites, with differences between white Christians and

...more

and it remains true that religiously unaffiliated whites are closer than white Christians to the attitudes of Christians of color. Religiously unaffiliated whites are far less likely than their Christian counterparts to perceive demographic and cultural changes as negative or to support policies designed to protect the country from such perceived external threats.

If the initial correlations we see between white supremacist attitudes and white Christianity cannot be explained away by other factors, white Christians have some serious soul-searching to do.

The models reveal that, in the United States today, the more racist attitudes a person holds, the more likely he or she is to identify as a white Christian. And when we control for a range of other attributes, this relationship exists not just among white evangelical Protestants but also equally strongly among white mainline Protestants and white Catholics.24 And there is also a telling corollary: this relationship with racist attitudes has little hold among white religiously unaffiliated Americans; if anything, the relationship is negative.

most white Christian churches have reformed very little of their nineteenth-century theology and practice, which was designed, by necessity, to coexist comfortably with slavery and segregation. As a result, most white Christian churches continue to serve, consciously or not, as the mechanisms for transmitting and reinforcing white supremacist attitudes among new generations.

Allowing this discomfort—and at times extreme anguish—to come, allowing the waves of the past to crash on the shore of the present until the rhythm is familiar enough to ring in the ears, is a critical step toward healing and wholeness. It is also perhaps the biggest challenge for us white Christians, who have been conditioned to move through our lives preoccupied with personal sin but unburdened by social injustice. The moral call now before us is not to solve an insurmountable problem but to begin a journey back to ourselves, our fellow citizens, and God.

“Love,” Baldwin writes, “takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” Love requires us to see who we really are and to respond to the voices still crying out to us from the ground.

But at this late point in our history, real reforms may arise only from the ashes of the current institutional forms of white Christianity.18 One thing is clear: any lasting changes will necessarily involve extreme measures to detect and eradicate the distortions that centuries of accommodations to white supremacy have created.

white Christian Americans, who still believe too easily that racial reconciliation is the goal and that it may be achieved through a straightforward transaction: white confession in exchange for black forgiveness. But mostly this transactional concept is a strategy for making peace with the status quo—which is a very good deal indeed if you are white. I am not trying to be cynical here, but merely honest about how little even well-meaning whites have believed they have at stake in racial reconciliation efforts. Whites, and especially white Christians, have seen this project as an altruistic

...more