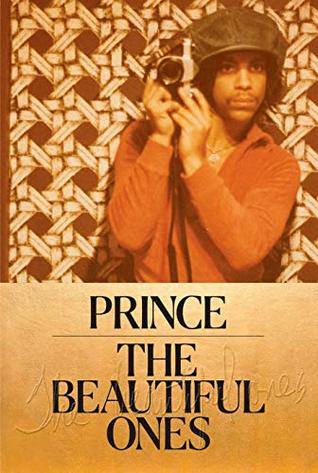

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

He agreed to put me on the list, but he didn’t mince words: The likelihood of my getting the gig fell somewhere between winning the lottery and surviving an asteroid impact. For one thing, I’d published zero books. At the time, I was an editor at The Paris Review, a literary magazine that I didn’t know if Prince had read or even heard of—no doubt his worst-selling album had found a wider audience than the Review ever had. I was twenty-nine. Next to the more seasoned hands up for the job, many of whom had loved Prince for longer than I’d been alive, I was a guaranteed also-ran.

Prince had developed fastidious ideas about which words belonged in his orbit and which did not. “Certain words don’t describe me,” he said. There were terms bandied about in the white critical establishment that demonstrated a complete lack of awareness of who he was. Actually, all the books about him were wrong because they embraced these white critical terms. Alchemy was one.

expect a call from Prince under the alias Peter Bravestrong—his preferred pseudonym, apparently, for traveling incognito. Later, at Paisley, I’d see that even his luggage was tagged “Peter Bravestrong.” I liked how obviously, almost defiantly, fictitious it sounded. Its comic-book gaudiness was in keeping with some of his past alter egos: Jamie Starr, Alexander Nevermind, Joey Coco. You could imagine them fighting crime together in a grim, neon city.

Whatever had compelled him to delete the bass line to “When Doves Cry” all those years ago was the same force moving him during these performances,

“A good ballad should always put U in the mood 4 making love,”

“Check your mailbox. There might be some funk in there.”

“Try to create,” Prince told me that day in Melbourne. “I want to tell people to create. Just start by creating your day. Then create your life.”

A good ballad should always put U in the mood 4 making love.