More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Richard Beck

Read between

June 10 - July 29, 2020

“His heart was so expansive and his mind so finely tuned that he could contain both darkness and light, love and trouble, fear and faith, wholeness and shatteredness, old-school and postmodern, the sacred and the silly, God and the Void. He was a Baptist with the soul of a mystic. He was a poet who worked in the dirt. He was an enlightened being who was wracked with the suffering of addiction and grief.”[4]

The author Flannery O’Connor once said her literary project was describing the action of grace in territory controlled by the devil.

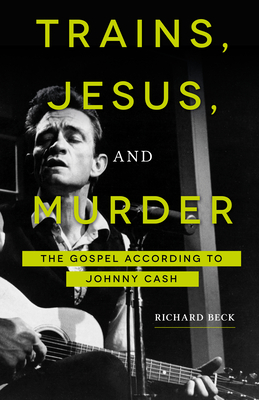

Trains, Jesus, and murder—somewhere in there is the gospel according to Johnny Cash.

When they got to the house, Ray Cash grabbed a blood-soaked paper bag that contained Jack’s torn and bloody clothes. “Come out to the smokehouse, J.R. I want to show you,” said Ray. Once in the smokehouse, Ray laid out Jack’s khaki pants, belt, shirt, and shoes. The pants had been cut from the rib cage down to the pelvis, cutting the belt in two. Staring at the torn, bloody clothes and marking the route the saw tore through Jack’s abdomen, Ray Cash began to cry. Trembling and traumatized, young J.R. stumbled out of the smokehouse. The reasons why Ray Cash felt the need to show Jack’s torn and

...more

“Dad was wounded so profoundly by Jack’s death, and by his father’s reaction—the blame and recrimination and bitterness. If someone survives that kind of damage, either great evil or great art can come out of it. And my dad had the seed of great art in him.”[5]

But if the gospel according to Johnny Cash is anything, it’s really not about our ability to walk the line. The gospel isn’t about our faithfulness to God; it’s about God’s faithfulness to us. Johnny Cash couldn’t walk the line. Nor can you or I or anyone else. God walks the line for us.

“The times when I was so down and out of it were also the times when I felt the presence of God. . . . I felt that presence, that positive power saying to me, ‘I’m still here.’”[5]

The first place to look for Christ is in Hell.”[1]

As Bono, the lead singer of U2, said about Cash, “Johnny Cash doesn’t sing to the damned, he sings with the damned, and sometimes you feel he might prefer their company.”[2]

As James Hetfield, from the heavy-metal band Metallica, said about Cash: “He’s speaking for the broken people—people who can’t speak up or no one wants to hear.”[3] It was not unlike Jesus touching the lepers.

The song is both protest and lament as Cash goes through a litany of suffering. In the lyrics, Cash stands in solidarity with the poor, the hungry, the hopeless, the addicts, the elderly, the incarcerated, the abandoned, the beaten down, and the forgotten soldier killed in war (Vietnam was raging at the time).

The gospel according to the Man in Black is a gospel rooted in solidarity. The cross of Christ, in this view, is an act of divine identification with the oppressed. On the cross, God is found with and among the victims of the world. More, given that crucified persons were considered to be cursed by God—“Cursed is anyone who is hung upon a tree” (Deuteronomy 21:23)—God is found in Jesus among the cursed and godforsaken. Again, the first place to look for Jesus is in hell.

Love moves. Love doesn’t stand in place. Solidarity implies involvement. Often, this involvement means physically relocating yourself in the world, to move and stand in a different spot, to find yourself among a different group of people. Solidarity is more than a hashtag or a Facebook post.

To express solidarity, I needed to put myself in a different physical location.

“After all the heavy breathing we do about God, it’s quite simply where one places one’s body that really counts. In other words, what part of town you live in, who you hang out with, who you work alongside. And above all how many social boundaries you cross in order to be with Jesus.”[5] Or, more simply, Myers goes on to say, “Hope is where your ass is.”

When pushed about why his attention focused on the men in prison rather than upon the victims, Cash once said, “People say, ‘well what about the victims, the people that suffer—you’re always talking about the prisoners: what about the victims?’ Well, the point I want to make is that’s what I’ve always been concerned about—the victims. If we make better men out of the men in prison, then we’ve got less crime on the streets, and my family and yours is safer when they come out.”[2]

But one thing Cash never lets them escape is regret.

As Cash observed, “I think prison songs are popular because most of us are living in one little kind of prison or another, and whether we know it or not the words of a song about someone who is actually in prison speak for a lot of us who might appear not to be, but really are.”[6]

Free or incarcerated, we’ve all experienced the alienation of “Folsom Prison Blues.” Prisoners of guilt, shame, loss, and regret, we observe the happy lives of others carrying on cheerfully. Spiritually, we hear the cell door slam, and we listen to the lonesome whistle pass and fade into the distance. People are traveling on to happiness and fulfillment, and we are left behind.

Words are nice, and so are songs, but when it comes to justice and love, it’s where you put your ass that ultimately matters.

And what that means, in a very real way, is that the inmates of Folsom Prison saved Johnny Cash.

All that to say, if the Folsom concert hadn’t gone well, Cash’s life could have turned out very differently, probably tragically. Cash went to Folsom looking for grace. And salvation came to him that day in the embrace of thieves, outlaws, and murderers.

We visit prisoners and shelter the homeless not to be like Jesus but to welcome Jesus. When we welcome the homeless and the incarcerated, we aren’t the saviors—we are the ones being saved.[8]

I was spiritually dry and looking for God. And the first place to look for God is in hell, right? So I started driving out to the prison, hoping that Jesus would show up as he promised in Matthew 25. Whenever we visit the prisoner, Jesus said, we visit him. I was desperately seeking Jesus, and he had told me where to look.

I found Jesus in the prison.

Rosanne Cash observed about her father’s relationship with Glen Sherley and others he tried to help, “You can’t hasten someone else’s recovery or enlightenment. I think my dad had a sense of maybe he could and it didn’t turn out well all the time.”[7]

We should remind ourselves of these sad outcomes whenever we talk about solidarity in the life of Johnny Cash.

Our trouble is this: We want solidarity and salvation to be the same t...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

First of all, when we confuse solidarity with salvation, we tend to objectify others. Whenever we see ourselves as saving people, we make ourselves the hero of the story, a moral...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

that story, the people we so nobly rescue are just moral props, passive recipients of our kindness and generosity. Ar...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

A lot of compassionate people fall into this trap, failing to see how our desire to save others can be ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Solidarity doesn’t presume we have the answers or the abil...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Solidarity makes us available to others, but it recognizes other’s competencies, seeing people as possessing the resources to help thems...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When we’re trying to save people, we’re talking and giving directions. With solidarity, we’re listening and receiving directions.

The currency of solidarity isn’t moral heroism—rescuing, fixing, and saving people. The currency of solidarity is relationship, mutuality, and friendship. And if that’s the case, we come face-to-face with the reality that relationships are risky and that we can’t guarantee the outcomes, no matter how hard we try. We aren’t in control, and some stories end sadly and tragically.

We keep trying to save people because to admit failure is to come face-to-face with loss. And fearing the pain of that loss, we refuse to give up, churning and churning away, fretting and worrying, trying to rescue someone, especially a person we dearly love. We don’t want to face the pain, so we keep trying to save them.

I’m not trying to give an apology for resignation, nor am I giving permission to give up on people. I’m just pointing out that our messiah complexes are often strategies for delaying and avoiding grief.

In trying to save the world, we’ll either exhaust ourselves or fall into depression—of...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Try as we might, some stories don...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

There is risk in rela...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Apathy keeps you numb, and the white horse makes you feel in control. Either way, it’s a strategy for avoiding heartbreak. Solidarity is the more difficult, more painful path.

Of course, I couldn’t give her an answer. No one can. And we all make different choices here. Tearfully and with hearts breaking, some of us do cut the string. We draw the line. Some of us can’t do that, choosing to fight until the bitter end, no matter the cost to our bank accounts or mental health. And no one can stand in judgment of either of these choices. We make them for reasons uniquely our own.

“The economy of love is paid in tears. Sooner or later, grief is the price we will pay for loving someone deeply and well. There is a price to love.”

“I don’t know the right choice; I can’t tell you what to do. But I can tell you this much. If you get to the grief, you’ve loved a person well. Most people don’t ever get to the tears. They’ve given up long ago. But you,” I told my friend, “you’ve loved a person deep into the pain. So the sadness, while hard, is holy ground. ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Solidarity can end with heartbreak. And if there is any good news to the sadness, it is this: you know you’ve loved a person well when you make it to the tears.

The pain, anger, and despair of the song “San Quentin” illustrate how expressions of solidarity can be harsh and bleak. Too often, the church sweeps past the suffering and sorrow of the world to get to the good news and the happy-ever-after ending. But the gospel doesn’t take shortcuts. Yes, there’s resurrection—but the cross came first. We get to the good news of Easter Sunday only after crying out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Lament isn’t the opposite of faith; rather, faith gives birth to lament.

Questioning and crying out to God are a deep, honest manifestation of faith.

think that serious religious use of the lament psalms has been minimal because we have believed that faith does not mean to acknowledge and embrace negativity. We have thought that acknowledgment of negativity was somehow an act of unfaith, as though the very speech about it conceded too much about God’s “loss of control.” The point to be urged here is this: The use of these “psalms of darkness” may be judged by the world to be acts of unfaith and failure, but for the trusting community, their use is an act of bold faith.[5]

Lament isn’t a failure or lack of faith. Lament is an act of bold, trusting faith in the midst of pain, suffering, and confusion. In fact, if we ignore lament, if we avoid giving voice to despair and rage, the gospel loses its ability to speak honestly, realistically, and truthfully. Without lament, faith grows naïve and superficial—a happy, fake, glossy façade we paint over the pain and confusion. In addition, lament is the cry of the oppressed, a song of resistance. When we avoid lament, we are marginalizing the voices crying out in pain around the world.