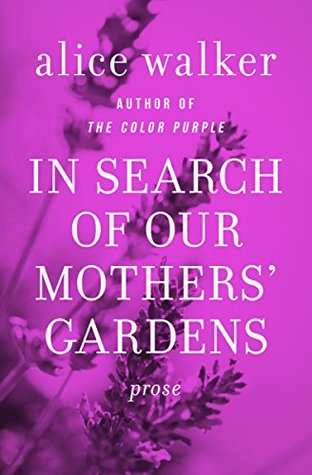

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

But please remember, especially in these times of groupthink and the right-on chorus, that no person is your friend (or kin) who demands your silence, or denies your right to grow and be perceived as fully blossomed as you were intended. Or who belittles in any fashion the gifts you labor so to bring into the world.

Zora was interested in Africa, Haiti, Jamaica, and—for a little racial diversity (Indians)—Honduras. She also had a confidence in herself as an individual that few people (anyone?), black or white, understood. This was because Zora grew up in a community of black people who had enormous respect for themselves and for their ability to govern themselves. Her own father had written the Eatonville town laws. This community affirmed her right to exist, and loved her as an extension of its self. For how many other black Americans is this true?

WHEN THE POET Jean Toomer walked through the South in the early twenties, he discovered a curious thing: black women whose spirituality was so intense, so deep, so unconscious, that they were themselves unaware of the richness they held. They stumbled blindly through their lives: creatures so abused and mutilated in body, so dimmed and confused by pain, that they considered themselves unworthy even of hope. In the selfless abstractions their bodies became to the men who used them, they became more than “sexual objects,” more even than mere women: they became “Saints.” Instead of being

...more

In the still heat of the post-Reconstruction South, this is how they seemed to Jean Toomer: exquisite butterflies trapped in an evil honey, toiling away their lives in an era, a century, that did not acknowledge them, except as “the mule of the world.” They dreamed dreams that no one knew—not even themselves, in any coherent fashion—and saw visions no one could understand. They wandered or sat about the countryside crooning lullabies to ghosts, and drawing the mother of Christ in charcoal on courthouse walls. They forced their minds to desert their bodies and their striving spirits sought to

...more

For these grandmothers and mothers of ours were not Saints, but Artists; driven to a numb and bleeding madness by the springs of creativity in them for which there was no release.

What did it mean for a black woman to be an artist in our grandmothers’ time? In our great-grandmothers’ day? It is a question with an answer cruel enough to stop the blood.

Black women are called, in the folklore that so aptly identifies one’s status in society, “the mule of the world,” because we have been handed the burdens that everyone else—everyone else—refused to carry.

Therefore we must fearlessly pull out of ourselves and look at and identify with our lives the living creativity some of our great-grandmothers were not allowed to know. I stress some of them because it is well known that the majority of our great-grandmothers knew, even without “knowing” it, the reality of their spirituality, even if they didn’t recognize it beyond what happened in the singing at church—and they never had any intention of giving it up.

And yet, it is to my mother—and all our mothers who were not famous—that I went in search of the secret of what has fed that muzzled and often mutilated, but vibrant, creative spirit that the black woman has inherited, and that pops out in wild and unlikely places to this day.

For example: in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., there hangs a quilt unlike any other in the world. In fanciful, inspired, and yet simple and identifiable figures, it portrays the story of the Crucifixion. It is considered rare, beyond price. Though it follows no known pattern of quilt-making, and though it is made of bits and pieces of worthless rags, it is obviously the work of a person of powerful imagination and deep spiritual feeling.

The question … is: What did it mean to be a Black lesbian/poet in America at the beginning of the Twentieth century? First, it meant that you wrote (or half wrote)—in isolation—a lot which you did not show and knew you could not publish. It meant that when you did write to be printed, you did so in shackles—chained between the real experience you wanted to say and the conventions that would not give you voice. It meant that you fashioned a few race and nature poems, transliterated lyrics, and double-tongued verses which—sometimes (racism being what it is)—got published. It meant, finally, that

...more

I understand the subtle programming I, my mother, and my grandmother before me fell victim to. Escape the pain, the ridicule, escape the jokes, the lack of attention, respect, dates, even a job, any way you can. And if you can’t escape, help your children to escape. Don’t let them suffer as you have done. And yet, what have we been escaping to? Freedom used to be the only answer to that question. But for some of our parents it is as if freedom and whiteness were the same destination, and that presents a problem for any person of color who does not wish to disappear.