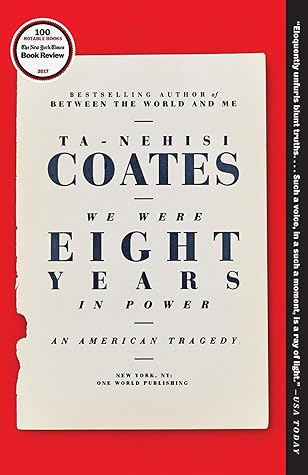

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 7 - October 16, 2017

“If there was one thing that South Carolina feared more than bad Negro government,” wrote Du Bois, “it was good Negro government.”

Obama, his family, and his administration were a walking advertisement for the ease with which black people could be fully integrated into the unthreatening mainstream of American culture, politics, and myth. And that was always the problem.

I know now that that hunger is a retreat from the knotty present into myth and that what ultimately awaits those who retreat into fairy tales, who seek refuge in the mad pursuit to be made great again, in the image of a greatness that never was, is tragedy.

In those days I imagined racism as a tumor that could be isolated and removed from the body of America, not as a pervasive system both native and essential to that body.

“gentrification” is but a more pleasing name for white supremacy, is the interest on enslavement, the interest on Jim Crow, the interest on redlining, compounding across the years, and these new urbanites living off of that interest are, all of them, exulting in a crime.

There was nothing new in this “birtherism,” in this attempt to deny African Americans the rights entitled to other American citizens, and there was nothing new in that denial’s power to organize a constituency.

Then I learned that nations were atheists, which is to say they find their strength not in any God but in their guns. The code of the streets was the code of the world.

Nothing in the record of human history argues for divine morality, and a great deal argues against it.

Ideas like cosmic justice, collective hope, and national redemption had no meaning for me. The truth was in the everything that came after atheism, after the amorality of the universe is taken not as a problem but as a given. It was then that I was freed from considering my own morality away from the cosmic and the abstract. Life was short, and death undefeated. So I loved hard, since I would not love for long. So I loved directly and fixed myself to solid things—my wife, my child, my family, health, work, friends. I found, in this fixed and godless love, something cosmic and spiritual

...more

Barack Obama governs a nation enlightened enough to send an African American to the White House, but not enlightened enough to accept a black man as its president.

An equality that requires blacks to be twice as good is not equality—it’s a double standard.

Love of country, like all other forms of love, requires that you tell those you care about not simply what they want to hear but what they need to hear.

This need to talk in dulcet tones, to never be angry regardless of the offense, bespeaks a strange and compromised integration indeed, revealing a country so infantile that it can countenance white acceptance of blacks only when they meet an Al Roker standard.

For Americans, the hardest part of paying reparations would not be the outlay of money. It would be acknowledging that their most cherished myth was not real.

in America there is a strange and powerful belief that if you stab a black person ten times, the bleeding stops and the healing begins the moment the assailant drops the knife.

In a time when communications were primitive and blacks lacked freedom of movement, the parting of black families was a kind of murder. Here we find the roots of American wealth and democracy—in the for-profit destruction of the most important asset available to any people, the family.

The American real-estate industry believed segregation to be a moral principle. As late as 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ code of ethics warned that “a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood…any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.” A 1943 brochure specified that such potential undesirables might include madams, bootleggers, gangsters—and “a colored man of means who was giving his children a college education and thought they were entitled to live among whites.”

I believe that wrestling publicly with these questions matters as much as—if not more than—the specific answers that might be produced. An America that asks what it owes its most vulnerable citizens is improved and humane. An America that looks away is ignoring not just the sins of the past but the sins of the present and the certain sins of the future.

Antebellum Virginia had seventy-three crimes that could garner the death penalty for slaves—and only one for whites.

I don’t ever want to forget, even with whatever personal victories I achieve, even in the victories we achieve as a people or a nation, that the larger story of America and the world probably does not end well. Our story is a tragedy. I know it sounds odd, but that belief does not depress me. It focuses me.

The Republican Party is not simply the party of whites, but the preferred party of whites who identify their interest as defending the historical privileges of whiteness.

Trump truly is something new—the first president whose entire political existence hinges on the fact of a black president.

Every Trump voter is most certainly not a white supremacist, just as every white person in the Jim Crow South was not a white supremacist. But every Trump voter felt it acceptable to hand the fate of the country over to one.

It is as if the white tribe united in demonstration to say, “If a black man can be president, then any white man—no matter how fallen—can be president.” And in that perverse way the democratic dreams of Jefferson and Jackson were fulfilled.

Americans, too, belong to a class—one responsible for and intrinsically tied to a history of torture, bombings, and coups d’état carried out in our name. And Trump has only heaped more upon that burden. In the global context, perhaps, we Americans are all white.