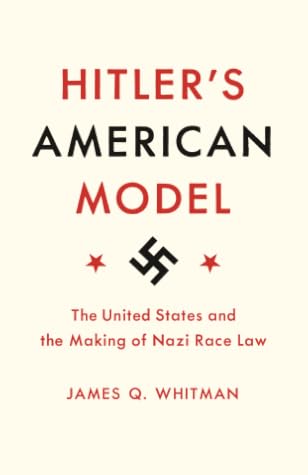

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 25 - April 2, 2019

He praised the American commitment to legislating racial purity, but he too blanched at “the unforgiving hardness of the social usage according to which an American man or woman who has even a drop of Negro blood in their veins,” counted as blacks.

The courts of some American states, in particular North Carolina and Texas, also looked to other “outward characteristics.” Texas in particular considered marital history:

The idea that race classifications might turn on something other than descent, and in particular on marital history, deserves to be flagged: that idea was of critical importance in the ultimate Nazi definition of “Jews.”

Did the American example count for something here? Krieger’s article was not the only possible source for the notion that a juristic solution to the problem of classifying Jews might turn in part on marital history. As we have seen, the Nazi literature on American immigration law praised the American Cable Act rule denaturalizing women who stooped to marry Asian men.168 It may have mattered, in the charged debates of the weeks after the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws, that America, the model of a country with anti-miscegenation law, offered some support for the notion that marital history

...more

What the history presented in this book demands that we confront are questions not about the genesis of Nazism, but about the character of America. The Nazis, let us all agree, would have committed monstrous crimes regardless of how intriguing and attractive they found American race law. But how did it come to pass that America produced law that seemed intriguing and attractive to Nazis?

And among the “Nordic” powers, America was the natural geopolitical model for Nazi Germany, as scholars have rightly noted. It was the “Anglo-Saxon” United States that had built an imposing continental empire, and that therefore stood out as an expansionist model for the Reich that was determined to conquer to its east. It was the “Anglo-Saxon” United States that had invented an international law doctrine that justified its place as a hegemon in its hemisphere, in the form of the Monroe Doctrine and its more assertive Roosevelt Corollary of 1904.

The South is static and defensive, not dynamic and aggressive.36

When we add it all up, the right conclusion is this: American white supremacy, and to some extent Anglophone white supremacy more broadly, provided, to our collective shame, some of the working materials for the Nazism of the 1930s. In that sense the history of Nazism cannot be fully told without a chapter on the “interesting results” that Otto Koellreutter identified in “the United States and the British Dominions.” But in Nazi Germany supremacist traditions and practices acquired the backing of a state apparatus far more powerful than anything to be found in the world of the daughters of

...more

Some of the most striking, and inescapable, questions have to do with the common-law tradition. What Freisler admired about American law is manifestly the same thing that we often celebrate in the common-law tradition today: the common law’s flexibility and open-endedness, and the adaptability to “changing societal requirements” that its judge-centered, precedent-based approach is often said to permit.

For the striking truth is that Nazi jurists were opposed to any theory of the law that reduced it to mere obedience. Yes it is the case that Germany was to be ruled by the Führerprinzip, the doctrine of obedience to the leader. But while it is true that ordinary citizens were to be blindly obedient, Nazi officials were expected to take a different attitude.

while ordinary Germans were to swear to obey the commands of the Führer unconditionally, “political leaders” were enjoined “to be loyal to the spirit of Hitler. Whatever you do, always ask: How would the Führer act, in accordance with the image you have of him.”

the contrary, the critical truth of legal history is that the Nazis set out to smash the traditional juristic attitudes of the civil-law jurist. Far from representing the traditions of the legalistic state, the Nazis belonged to a culture of contempt for the ways continental lawyers had been trained to work. Nazi radicals understood themselves to be, in the words of Hans Frank’s “greeting” to the forty-five lawyers who gathered on the SS Europa in September 1935, a movement that opposed the “outdated type of jurist, always inclined to ignore the realities of life,”

As for American common-law judges, unlike German “legal scientists” such as Lösener they showed no sign of concern about the conceptual incoherence of their racist decisions. Where Lösener insisted that criminalization was at best problematic in the absence of a scientifically defensible definition of a “Jew,” American common-law judges, as Freisler approvingly noted, simply improvised their conceptions of “coloreds” as they went along. That was the racist America that commanded the respect of radical Nazi lawyers: it was an America where politics was comparatively unencumbered by law.

this means, the law would institutionalize and perpetuate a savage form of national revolution, by giving discretion to the savage instincts of innumerable Hitlers in innumerable state offices. It would create a Nazi hydra. That is precisely how Freisler conducted himself in office as President of the People’s Court. And that was why the jurisprudence of the common law, with its “pragmatism,” its “immediacy,” its surrender of lawmaking authority to the judges, attracted him so much.

The association between this American Legal Realism and the New Deal is close indeed,57 and American lawyers often express considerable pride in their realist tradition, “the most important indigenous jurisprudential movement in the United States,” as Brian Leiter writes, “during the twentieth century.”58 Meanwhile the economic programs of the early New Deal were undertaken in a closely related pragmatic spirit. As Franklin Roosevelt described the American mood in a famous 1932 speech, “the country demands bold, persistent experimentation.

Nazi courts descended into appalling

depths of lawlessness.

Krieger saw that the deep tension in American race law was no different from the deep tension in American economic law: as he put it, the United States was a country torn between the two “shaping forces” of formalism and realism.

But to have a common-law system like that of America is to have a system in which the traditions of the law do indeed have little power to ride herd on the demands of the politicians, and when the politics is bad, the law can be very bad indeed.

“There is currently one state,” wrote Adolf Hitler, “that has made at least the weak beginnings of a better order.” When one thinks of race law, said Nazi lawyer and later SS-Obersturmbannführer Fritz Grau, one thinks of “North America.” “It is attractive to seek foreign models,” declared Reich Minister of Justice Franz Gürtner, and like others before them, it was American models that the lawyers of the ministry found. To be sure, America had failed to target the Jews “so far,” as Heinrich Krieger acknowledged, but apart from that “exception,” declared Roland Freisler, hanging judge of the

...more

See also the clever speculations of a student paper published in 2002: Bill Ezzell, “Laws of Racial Identification and Racial Purity in Nazi Germany and the United States: Did Jim Crow Write the Laws That Spawned the Holocaust?,” Southern University Law Review 30 (2002–3): 1–13.

Though perhaps he was not too far off: criminal prosecution was “sporadic.” See Pascoe, What Comes Naturally, 135–36.

Heinrich Krieger, “Principles of the Indian Law and the Act of June 18, 1934,” George Washington Law Review 3 (1935): 279–308, 279.

Bill Ezzell, “Laws of Racial Identification and Racial Purity in Nazi Germany and the United States: Did Jim Crow Write the Laws That Spawned the Holocaust?,” Southern University Law Review 30 (2002–3): 1–13; Judy Scales-Trent, “Racial Purity Laws in the United States and Nazi Germany: The Targeting Process,” Human Rights Quarterly 23 (2001): 259–307.