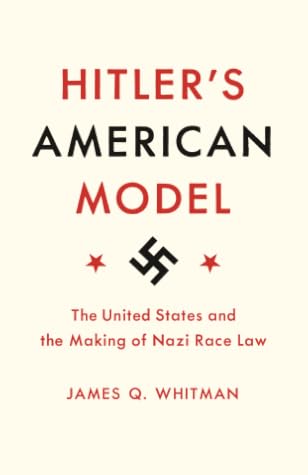

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

May 13 - May 15, 2019

Freisler further argued that there was something to learn from the techniques of American judging. American judges had no trouble applying racist law despite its fuzzy concepts.

These states obviously all have an absolutely unambiguous jurisprudence, and this jurisprudence would suit us perfectly

What the American example showed was that German judges could persecute Jews even without legislation founded in clear and scientifically satisfactory definitions. “Primitive” concept formation would suffice. In fact, Freisler maintained, it would be perfectly workable if German race legislation too, following the American lead, simply specified “coloreds”:

It seems to me doubtful that there would be any need to expressly mention the Jews alongside the coloreds. I believe that every judge would reckon the Jews among the coloreds, even though they look outwardly white, just as they do the Tatars, who are not yellow. Therefore I am of the opinion that we can proceed with the same primitivity [Primitivität] that is used by these American states. A state even simply says: “colored people.” Such a procedure would be crude [roh], but it would suffice.

That was the racist America that commanded the respect of radical Nazi lawyers: it was an America where politics was comparatively unencumbered by law.

Nazi law was law that was liberated from the juristic past—it was law that would free the judges, legislators, and party bosses of Nazi Germany from the shackles of inherited conceptions of justice, allowing them to “work toward” the realization of the racist goals of the regime, with a sense of their duty to use their discretion in the spirit of Adolf Hitler.

By this means, the law would institutionalize and perpetuate a savage form of national revolution, by giving discretion to the savage instincts of innumerable Hitlers in innumerable state offices. It would create a Nazi hydra.