More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 12 - February 19, 2022

“After blood, wine is the most complex matrix there is.”

Sommeliers should turn clockwise, only, around a table.)

I found out later that one contestant had taken dancing lessons to perfect his elegant walk across the floor. Another hired a speech coach to help him modulate his voice into a velvety baritone, plus a memory expert to strengthen his recall of vineyard names. Others consulted sports psychologists to learn how to stay cool under pressure.

I felt like these sommeliers and I existed at opposite extremes: While my life was one of sensory deprivation, theirs was one of sensory cultivation.

(The word “sommelier” comes from sommier, Middle French for packhorse.)

More than any other edible thing on this planet, wine is celebrated as part and parcel of a civilized life. Robert Louis Stevenson called wine “bottled poetry,” and Benjamin Franklin declared it “constant proof that God loves us”—things

When I drank a glass of wine, it was as if my taste buds were firing off a message written in code. My brain could only decipher a few words. “Blahblahblahblah wine! You’re drinking wine!” But to connoisseurs, that garbled message can be a story about the iconoclast in Tuscany who said Vaffanculo! to Italy’s wine rules and planted French Cabernet Sauvignon vines, or the madman vintner who dodged shell fire and tanks to make vintage after vintage all through Lebanon’s fifteen-year civil war.

I began to notice a paradox in our foodie culture. We obsess over finding or making food and drink that tastes better—planning travel itineraries, splurging on tasting menus, buying exotic ingredients, lusting after the freshest produce. Yet we do nothing to teach ourselves to be better tasters.

It seemed possible for any of us to relish richer experiences by tuning into the sensory information we overlook. And I was thirsty to give it a go.

Taste is not just our default metaphor for savoring life. It is so firmly embedded in the structure of our thought that it has ceased to be a metaphor at all.

There was no class I could take to pass the Certified. Instead, what the Court provides is a two-page reading list consisting of eleven books and three wine encyclopedias.

“You can’t make margin on shit people don’t know”—some somms would offer their favorite obscure wines at a lower markup, then make up the difference with the gimmes.

Love of fine flavors, I was learning, could trump the push for profit.

The process is deliberately complicated. Following the repeal of Prohibition, lawmakers introduced the middlemen—distributors—hoping they’d prevent the rise of a Big Booze lobby, make it more expensive and less efficient to buy alcohol, and thus save us from becoming a nation of cirrhosis-afflicted binge drinkers.

“Wine,” declared the nineteenth-century novelist Alexandre Dumas, “is the intellectual part of the meal.”

The lucky individual charged with serving wine has enjoyed a privileged position relative to other servants and staff. Wine is special—the ancients believed it had divine origins—and by extension, so are the people who handle it.

One of the earliest references to a “sommelier” (the word hadn’t yet been invented) appears in the Book of Genesis. Cupbearers, who poured and served wine, were the confidants and counselors of Egyptian kings, and in a biblical story, Pharaoh calls on his wine steward for help making sense of a dream.

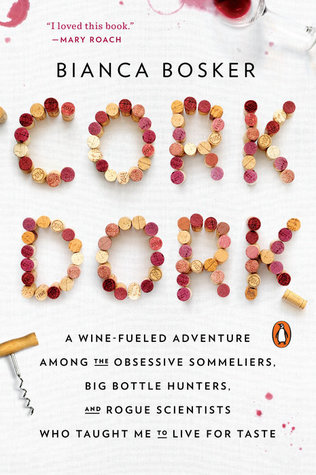

The somms’ affectionate nickname for one another: “cork dork.”

He wanted me to know that the most expensive wines on the Titanic had all been German Rieslings.

show you knew your Meursault (a Chardonnay grown in Burgundy’s Meursault village) from your Marsannay (a Chardonnay grown about twenty miles over in Burgundy’s Marsannay village).

Michael Jackson Really Makes Small Boys Nervous.’ So Michael is Magnum; Jackson is Jeroboam; really, Rehobaum; makes, Methuselah; small, Salamanzar; boys, Balthazar; nervous, Nebuchadnezzar.” (With slight variations depending on the region, a magnum contains the equivalent of two standard bottles; a Jeroboam holds four; a Rehobaum, six; a Methuselah, eight; and from there the volume increases by four bottles per size up through the Nebuchadnezzar, which holds twenty standard bottles and guarantees a good time.)

Morgan has always blazed through his passions like a forest fire, consuming everything in his path. “My brain has a tendency to want to organize small differentiating units into systems,” he told me. “Part of it is my desire to complete. To know a thing in its entirety, or as close to it as you can.”

he couldn’t be in wine without taking it to its illogical extreme. All the while, he threw himself into books, competitions, classes, and tastings. This wasn’t just about selling good bottles. He believed that wine could reshape someone’s life.

(A quick warning: oenophiles use an unnecessary number of French words in daily life. Towel is serviette, bubbles are pétillance, and table settings are the mise-en-place. Pretentious? Oui.)

Morgan plunged into the five key attributes that make up the “structure” of a wine: sugar, acid, alcohol, tannins, and texture, also referred to as “body.”

Thick, slow tears with clear definition suggest the wine has higher alcohol levels, where thin, quick tears, or wine that falls in sheets, hint at lower alcohol levels.

Next, spit it out or swallow. Place the tip of your tongue against the roof of your mouth, and pay attention to how much you salivate. A lot or a little? Swimming pool or sprinkler? If you’re not sure, tip your head forward so your eyes are facing the floor. If you opened your mouth right now, would you drool? If so, you’re tasting a higher-acid wine. If not, it’s likely a lower-acid wine. (The former tends to hail from cooler growing regions, and the latter from warmer areas.)

(Contrary to tasting notes, nothing like honeysuckle, peach, or orange Tic Tacs is added to the wine to flavor it, though some stray spiders, rats, mice, and snakes scooped up from the vineyard can accidentally get mixed in.)

Warmer climates lead to riper grapes with a higher concentration of sugar, which, by the laws of fermentation, will produce wines with higher alcohol.

Tannins are more a texture than a taste, and therefore distinct from whether the wine is “dry,” which refers to the absence of sweetness. And yet, confusingly, tannins leave your mouth feeling dried-out and grippy—more like sandpaper for tannic wines (like young Nebbiolo), or like silk for low-tannin wines (say, Pinot Noir). Some tasters swear they can differentiate between tannins that come from grapes, which make their tongues and the roof of their mouths feel rough, and tannins from oak barrels, which dry out the spot between their lips and gums.

And since residual sugar can make wines more viscous, you can also sense sweetness by feeling out the weighty thickness or pillowy softness of a wine.

Prolonged exposure to a scent makes our noses temporarily “blind” to that odor, a process known as olfactory fatigue.

he expounded on the problematic—and prevalent—mentality among American diners of expecting restaurants to humor their every whim, instead of them opening themselves up to the new and unfamiliar.

“We use the analogy of a swan. We look smooth and calm on top, but we’re pedaling frantically underneath,” Jon told me during a break. “It has to be perfect.”

It took almost a century, until about the 1970s, to figure out that the tongue map was bogus, a scientific gaffe arising from a mistranslation of a German student’s 1901 PhD dissertation.

Another common misconception is that the tongue is your body’s only taste interpreter. In fact, there are taste receptors on your epiglottis, as well as in your throat, stomach, intestines, pancreas, and, if you’re a man, your sperm and testes.

Besides sweet, bitter, salty, sour, and umami—that meaty, savory intensity in foods like soy sauce and cooked mushrooms—scientists have argued for expanding the club of basic tastes to include water, calcium, metallic, “soapy,” and fat (“oleogustus”).

To the connoisseur, the pairing of wine and glass demands as much care as the pairing of wine and food.

Glassmakers claim the shape of a glass’s bowl accentuates certain flavors and textures in the wine—sometimes, ostensibly, by controlling where the wine hits the tongue, or how much air hits the surface of the wine. Riedel, an industry leader, goes so far as to sell glasses customized to more than a dozen grapes and regions, including one glass for “Bordeaux Grand Cru” ($125 each) and a different one for “Mature Bordeaux” ($99 apiece). Pity the rube who desecrates a Chablis by pouring it into Riedel’s “Alsace” glass.

The short answer: Yes, they are justified (and no, Solo cups aren’t a substitute). Five different studies have shown glass shape can, in subtle but noticeable ways, mute or enhance wine aromatics, though not necessarily in the specific manner Riedel, Zalto, and other glassmakers claim. In general, glasses that are wider around the middle and narrower at the top increase the aromatic intensity of the wine more than other models.

Marea keeps files on its guests—their pet peeves, personal quirks, dining histories, and importance to the restaurant—and communicates the information to the staff via soignés, paper tickets that print as soon as a table is seated, so everyone on duty knows how to treat the

A soigné marked “ATG” means “according to Google,” as in “ATG investment banking analyst at Barclays Capital.”

watched an ABC News interview in which billionaire Bill Koch gets choked up thinking about his cellar—this from the unsentimental oil magnate who waged a brutal twenty-year legal battle against his own brothers. “Can any wine be worth $25,000 or $100,000 a bottle?” a reporter asks Koch. “A normal person says, ‘Hell no, it isn’t,’” Koch replies. “But for me, the art”—here Koch clears his throat—“craftsmanship”—his voice cracks on the final syllable and he blinks a few times to stop the tears that have started to come.

More than a million dollars’ worth of wine shows up for the final dinner, I was told. The dump buckets alone would contain some $200,000 worth of tossed Pinot and Chardonnay. “La Paulée is the kind of thing that starts revolutions in countries,”

Burgundy has a reputation as the most overwhelmingly complex wine region on the planet, which is exactly what its devotees love about it. You don’t just decide to be a Burgundy fan. You have to earn it.

To be fair, in certain respects Burgundy is a much simpler region than others. With a few exceptions, Burgundy’s white wines are made from Chardonnay and its reds from Gamay or Pinot Noir, a fussy weakling of a grape that’s far more delicate and disease-prone than its happy-go-lucky cousin Cabernet Sauvignon. But that is where Burgundy’s simplicity ends.

When he got to the names of Rajat Parr, Patrick Cappiello, and Larry Stone—three of the industry’s celebrity somms—people around me audibly gasped.

“Do you think wine can ever be better than sex?” I heard the hedge-fund manager next to Laurent ask his date. “Vega Sicilia,” she answered, without missing a beat. “It’s a joy to the world.”

La Paulée was, in its own way, a laboratory that proved flavor does not come only from our nostrils and mouth, as we often assume. We savor with our minds.

The scientists concluded that our brains derive satisfaction not solely from what we experience—those aromatic molecules tickling our noses and tongues. Rather, we’re delighted by what we expect we’ll perceive.