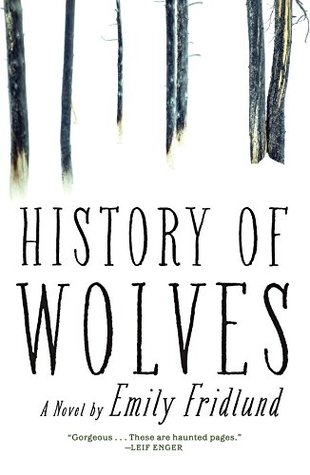

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

What, a history of wolves?” He was puzzled. Then he shook his head and grinned. “Right. You’re a fourteen-year-old girl.” The skin bunched up around his eyes. “You all have a thing for horses and wolves. I love that. I love that. That’s so weird. What is that about?”

My mother believed in God, but grudgingly, like a grounded daughter.

She looked both older and younger at once. A kid dressing up, or a middle-aged lady trying too hard to look young.

After I met Leo, I changed it. Who could be named Leo and Cleo?” She sounded defensive. “In what world would that work?” It would not. She was right.

As if we hadn’t gone through these same pleasantries five minutes before, as if she could, with discipline, deal with my distressing peculiarities the way you dealt with an unfortunate accent or a child chewing her nails.

You know how summer goes. You yearn for it and yearn for it, but there’s always something wrong. Everywhere you look, there are insects thickening the air, and birds rifling trees, and enormous, heavy leaves dragging down branches. You want to trammel it, wreck it, smash things down. The afternoons are so fat and long. You want to see if anything you do matters.

Winters were especially confining. We were all tied—as if by rope—to that sooty black furnace. Which has a certain romance, I know, if you tell the story right, a certain Victorian ghost-story earnestness people like, and I’ve told the story that way to the delight of shark-tooth-wearing dates in coffee shops. So many people, even now, admire privation. They think it sharpens you, the way beauty does, into something that might hurt them. They calculate their own strengths against it, unconsciously, preparing to pity you or fight.

Didn’t she always need someone to watch her and approve? And wasn’t I better at that than anyone?