More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 6 - July 18, 2023

Enuf and enough are very different words. They have the same meaning, can be used in the same context, but each has very different significance to those who employ them. Enuf sits comfortably in the subtitle of a book like For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide, allowing the work to call out to those for and about whom it is written.

It prepares the reader for the substance of the text.

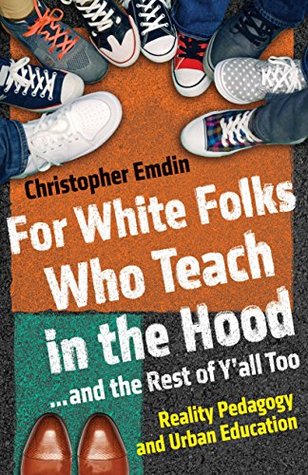

In many ways, this book draws from the traditions set forth by Shange. While it is neither a collection of poems and stories nor a theater piece, its intentions are similar. The title works toward invoking necessary truths and offering new ways forward. It is clearly intended for “white folks who teach in the hood.” But it is also for those who work with them, hire them, whose family members are taught by them, and who themselves are being, or have been, taught by them.

In all cases, they are so deeply committed to an approach to pedagogy that is Eurocentric in its form and function that the color of their skin doesn’t matter.

What I am suggesting is that it is possible for people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds to take on approaches to teaching that hurt youth of color. Malcolm X described this phenomenon in a powerful speech about the house Negro and the field Negro in the slave South. He described the black slave who toiled in the fields and the house Negro who worked in the white master’s house. He noted that at some point, the house Negro became so invested in the well-being of the master that the master’s needs and concerns took preeminence over his own needs and that of the field Negro. This is the

...more

The ideology of the Carlisle School is alive and well in contemporary urban school policies. These include zero tolerance and lockdown procedures. A student in a school I recently visited described the innocuous term school safety as a “nice-sounding code word for treating you like you’re in jail or something.” In urban school districts across the country, school safety personnel are uniformed officers who are part of the police force and often engage in discriminatory practices that reflect those in the larger community.

However, it and programs like it tend to exoticize the schools they serve and downplay the assets and strengths of the communities they are seeking to improve. I argue that if aspiring teachers from these programs were challenged to teach with an acknowledgment of, and respect for, the local knowledge of urban communities, and were made aware of how the models for teaching and recruitment they are a part of reinforce a tradition that does not do right by students, they could be strong assets for urban communities. However, because of their unwillingness to challenge the traditions and

...more

What new lenses or frameworks can we use to bring white folks who teach in the hood to consider that urban education is more complex than saving students and being a hero? I suggest a way forward by making deep connections between the indigenous and urban youth of color.

The neoindigenous will continue to exist, and need to be acknowledged, in classrooms for as long as traditional teaching promotes an imaginary white middle-class ideal. As long as white middle-class teachers are recruited to schools occupied by urban youth of color, without any consideration of how they affirm and reestablish power dynamics that silence students, issues that plague urban education (like achievement gaps, suspension rates, and high teacher turnover) will persist.

For teachers to acknowledge that the ways they perceive, group, and diagnose students has a dramatic impact on student outcomes, moves them toward reconciling the cultural differences they have with students, a significant step toward changing the way educators engage with urban youth of color.

Consider, for example, the denial of the genocide of Aboriginal Australians by former prime minister John Howard despite reports and testimonials that confirmed the horrors they endured. This same denial exists today with neoindigenous populations who are pushed out of schools and into prisons and who can clearly articulate the personal devaluation they undergo in urban public schools. On a recent visit to a prison where I was speaking to young men of color who had been incarcerated for anywhere from two to twenty years, I struck up a conversation with a group of young men who described a

...more

Despite its prominence, however, it is not part of the existent discourse on urban teaching and learning. When I mention it in academic circles, I am always challenged to think about it as the exception and not the norm. This denial of my reality in academic spaces signals more than individual denials of others’ histories; it is a systemic denial within institutions built upon white cultural traditions that oppress and silence the indigenous and the neoindigenous.

Like the indigenous, who have been relegated to certain geographic areas with little resources but still find a way to maintain their traditions, the neoindigenous in urban areas have developed ways to live within socioeconomically disadvantaged spaces while maintaining their dignity and identity. They are blamed for achievement gaps, neighborhood crime, and high incarceration rates, while the system that perpetuates these issues remains unchallenged. In urban schools, where the neoindigenous are taught to be docile and complicit in their own miseducation and then celebrated for being

...more

Students quickly receive the message that they can only be smart when they are not who they are. This, in many ways, is classroom colonialism; and it can only be addressed through a very different approach to teaching and learning.

Consider, for example, the growing number of new charter schools in urban communities with words like success, reform, and equity in their names and mission statements, but which engage in teaching practices that focus on making the school and the students within it as separate from the community as possible.

Furthermore, he alludes to the major premise of this work—that what lies beyond what we see are deep stories, complex connections, and realities that factors like race, class, power, and the beliefs/presuppositions educators hold inhibit them from seeing. Teaching to who students are requires a recognition of their realities.

Framing urban youth as neoindigenous, and understanding that the urban youth experience is deeply connected to the indigenous experience, provides teachers with a very different worldview when working with youth. From this new vantage point, teachers can see, access, and utilize tools for teaching urban youth. An understanding of neoindigineity allows educators to go beyond what they physically see when working with urban youth, and attend to the relationship between place and space.

This type of healing work is necessary for the neoindigenous as well. Situations such as the suspension of the student who believed she was prepared for class and always on time result in soul wounds that are bigger than the disciplinary issue itself and could be avoided if the teacher validated the student’s emotion by allowing her to articulate her feelings. Recognizing the neoindigeneity of youth requires acknowledgement of the soul wounds that teaching practices inflict upon them.

Reality pedagogy is an approach to teaching and learning that has a primary goal of meeting each student on his or her own cultural and emotional turf.

focuses on making the local experiences of the student visible and creating contexts where there is a role reversal of sorts that positions the student as the expert in his or her own teaching and learning, and the teacher as the learner. It posits that while the teacher is the person charged with delivering the content, the student is the person who shapes how best to teach that content. Together, the teacher and students co-construct the classroom space.

This means that the teacher does not see his or her classroom as a group of African American, Latino, or poor students and therefore does not make assumptions about their interests based on those preconceptions.

we approached the arrival of the students with an unhealthy apprehension about what the next academic year would bring.

The process was subtle and took different forms for each of the teachers who stood in the auditorium that morning. For many of the white teachers, the process held an unmistakable element of racism. Phrases like “these kids” or “those kids” were often clearly code words for bad black and brown children.

These scholars argue that black youth view doing well in school as acting white, without considering that teachers may perceive being black as not wanting to do well in school.

It is that they typically see white teachers as enforcers of rules that are unrelated to the actual teaching and learning process. Consequently, they respond negatively to whatever structures these teachers value even at the expense of their own academic success.

Unbeknownst to me, I was the loser in a larger game, missing out on what was being taught in the classroom and drawn into another game of cat and mouse with security officials who patrolled the building in search of students like me who were leaving class out of boredom, frustration, or just a chance to breathe.

Then, as I’d navigated the landscape of formal education and played a game whose rules were enforced largely by white folks who teach in the hood, I became conditioned to be a “proper student” and began to lose value for pieces of myself that previously defined me.

the constant reminder by peers, family members, teachers, and now school administrators to see urban youth of color as a group that is potentially dangerous and needs to be saved from themselves. We were both told not to express too much emotion with students or be too friendly with them. I was told to “stand your ground when they test you,” “don’t let them know anything about your life so they don’t get too familiar,” and “remember that there is nothing wrong with being mean.” Everyone from whom we solicited advice shared a variation of the phrase “Don’t smile till November.”

And because being in touch with one’s emotions is the key to moving from the classroom (place) to the spaces where the students are, our students were invisible to us.

White folks who teach in the hood are particularly prone to this sort of rote model. This is especially the case if they are convinced that having all students pass tests creates some form of equity. In these cases they are so married to a curriculum that is sold as the only path to passing the test that there is no willingness to deviate from it even if it is harming students. Furthermore, teaching to an exam and strictly following a curriculum makes it easier for these teachers to remain emotionally disconnected from students.

Despite my efforts to convince the teacher that her personal stories could have helped her engage her students, she was adamant in her belief that sharing them would have undermined her in some way. This same teacher was one of many who later complained at the end of the academic year about how poorly students did on the standardized test she was so intent on teaching to.

In each of the scenarios described above, the white teachers held perceptions about the students and the type of instruction they needed that were rooted in bias.

These biases were then used to justify ineffective teaching that is absolved from critique because of its supposed alignment to standardized exams.

In reality, the persistence of achievement gaps proves that teaching that is not personalized and not hands-on (as is most teaching in traditional urban schools) does not equate to success on standardized exams. It also should lead to conversations about how these approaches to teaching actually support the persistence of the gaps they are designed to close.

These same students exhibit resilience, dedication, and hard work in a number of tasks in their neighborhoods and devote hours on end to supporting each other in activities that have real meaning.

In that moment, she uncovered how prevalent that “mean” style of teaching was, but also displayed her incredible resilience. I had perceived her as disconnected and disinterested in school, even though she was obviously the opposite of that. Unfortunately, I’d had no structures in place at the time to forge a connection with this student and allow her to tap into the resilience that brought her to school every day and help her apply it in my class.

However, the key to getting students to be academically successful (even if the teacher decides that success means passing an exam), is not to teach directly to the assessment or to the curriculum, but to teach directly to the students. Every educator who works with the neoindigenous must first recognize their students’ neoindigeneity and teach from the standpoint of an ally who is working with them to reclaim their humanity.

For white folks who teach in the hood, this may require a much more intense unpacking. For me, this meant taking the time to analyze why I was initially scared of my students and moving beyond that fear, acknowledging that getting to know my students and having them know me may alter the power structure and affect classroom management.

The entire system of urban education is failing youth of color by any number of criteria, the structure of the traditional urban school privileges poor teaching practices, these practices trigger responses from students that reflect “poor behavior,” the poor behavior triggers deeply entrenched biases that teachers hold, and when this triggering of biases is coupled with the cycling in and out of white folks to teach in the hood, former teachers with activated biases leave urban classrooms to become policymakers and education experts who do not believe in young people or their communities.

In response, I suggest an approach to urban education that benefits the two most significant parties in the traditional school—the student and the teacher—an approach to teaching and learning that not only considers what is right for students, but what makes the teacher most effective and fulfilled. This vision of teaching doesn’t hide the fact that challenges in urban education persist because of our collective investment in maintaining a system that is intent on forcing brilliance to silence itself and then dealing with the varied repercussions. Once educators recognize that they are biased

...more

Our understandings of who was and wasn’t a good student were rooted less in our experiences with urban students and more on our perceptions of them, which were largely based on a flawed narrative.

The teacher must work to ensure that the institution does not absolve them of the responsibility to acknowledge the baggage they bring to the classroom and analyze how that might affect student achievement. Without teachers recognizing the biases they hold and how these biases impact the ways they see and teach students, there is no starting point to changing the dismal statistics related to the academic underperformance of urban youth.

The scene described here is emblematic of hundreds of visits I made to Pentecostal black churches across urban America in preparation for writing this book. These spaces share rules of engagement and general norms and traditions that serve as powerful models for white folks who teach in the hood and can be used to transform the classroom.

The beauty of the process I had witnessed in Harlem could be narrowed down to the preacher’s awareness of the delicate balance between structure and improvisation.

They both use call-and-response (e.g., asking the congregation the question “Can I get an amen?” and waiting for the audience to put their hands up and respond) to ensure the crowd is engaged, use the volume of their voice to elicit certain types of responses, actively work the room, and make references to contemporary issues or respond to cues in the immediate environment to enliven their planned/scripted sermons and performances. I argue that the use of these techniques, which fall under the umbrella of Pentecostal pedagogy, is necessary for teaching urban youth of color. Pentecostal

...more

Pentecostal pedagogy requires a different view of teaching itself. Here, teaching is a process where a context is created in which information is exchanged among people with the end result being an increase in the knowledge/information of everyone who takes part.

It requires an understanding of, and appreciation for, the unique cultural dimensions of neoindigeneity. It considers those aspects of their experience that connect urban youth to their indigenous counterparts and utilizes them to create the appropriate classroom space. It considers the language of the students, and incorporates it into the teaching by welcoming slang, colloquialisms, and “nonacademic” expressions, and then uses them to introduce new topics, knowledge, and conversations. It acknowledges and provides an escape from everyday oppression (which may come from interactions with the

...more

In other words, using the culture of the youth, which teachers often view as antiacademic, ends up helping these youth in the classroom.

In each of these studies, the key theme that emerged was the potential of youth language and experience to positively impact teaching. These studies confirm that employing indigenous and neoindigenous youth knowledge is the key to teaching neoindigenous people. I argue that additionally, the optimal way for youth language and experience to be used as a teaching tool involves having the youth themselves do the teaching.

I propose a reality pedagogy–based version of coteaching. This version deconstructs the ways that we previously have viewed coteaching by identifying and focusing on the transformative power of having more than one classroom leader/teacher in the classroom, and then extending the role of teacher/leader to students. This may require positioning the traditional teacher as a student in the classroom. Coteaching within reality pedagogy involves the transfer of student/teacher roles so that everyone within the classroom can gain the opportunity to experience teaching and learning from the other’s

...more