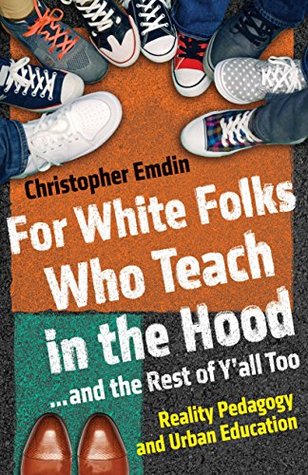

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 28 - September 2, 2019

In New York public schools, over 70 percent of high school youth are students of color, while over 80 percent of public high school teachers in the state are white.

While some may use these statistics to push for more minority teachers, I argue that there must also be a concerted effort to improve the teaching of white teachers who are already teaching in these schools, as well as those who aspire to teach there, to challenge the “white folks’ pedagogy” that is being practiced by teachers of all ethnic and racial backgrounds.

Unfortunately, because many of these students were far from the support of their Native communities, they were forced to assimilate to the culture of the teachers and the school so as to avoid the harsh punishments that would otherwise be levied on them.

the eventual recognition that the Carlisle School was a failed experiment.

The media praised the “riot mom” for how she addressed the situation—she was widely hailed as “Mother of the Year”—but in so doing perpetuated the narrative of young black boys requiring a tough hand to keep them in line.

In urban communities that are populated by youth of color, there are other, and oftentimes unwritten, expectations like having strong classroom-management skills and not being a pushover. In this case, care is expressed through “tough love.”

Because of the similarities in experience between the indigenous and urban youth of color, I identify urban youth as neoindigenous.

The neoindigenous often look, act, and engage in the classroom in ways that are inconsistent with traditional school norms. Like the indigenous, they are viewed as intellectually and academically deficient to their counterparts from other racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. Too often, when these students speak or interact in the classroom in ways that teachers are uncomfortable with, they are categorized as troubled students, or diagnosed with disorders like ADD (attention deficit disorder) and ODD (oppositional defiant disorder).

Addressing the cultural differences between teachers and students requires what educational researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings describes as culturally relevant pedagogy.7 This approach to teaching advocates for a consideration of the culture of the students in determining the ways in which they are taught.

exoticizes neoindigenous language, but still holds a general perception that it represents lowbrow antiacademic culture.

“politics of indigeneity,”9 which reinforces power structures that privilege certain voices while silencing and attempting to erase the history and value of others.

Educators are trained to perceive any expression of neoindigenous culture (which is often descriptive and verbal) as inherently negative and will only view the students positively when they learn to express their intelligence in ways that do not reflect their neoindigeneity. Students quickly receive the message that they can only be smart when they are not who they are. This, in many ways, is classroom colonialism; and it can only be addressed through a very different approach to teaching and learning.

The work for white folks who teach in urban schools, then, is to unpack their privileges and excavate the institutional, societal, and personal histories they bring with them when they come to the hood.

The reality is that we privilege people who look and act like us, and perceive those who don’t as different and, frequently, inferior.

The idea that one individual or school can give students “a life” emanates from a problematic savior complex that results in making students, their varied experiences, their emotions, and the good in their communities invisible.

In schools, urban youth are expected to leave their day-to-day experiences and emotions at the door and assimilate into the culture of schools.

The work to become truly effective educators in urban schools requires a new approach to teaching that embraces the complexity of place, space, and their collective impact on the psyche of urban youth.

Urban youth are typically well aware of the loss, pain, and injustice they experience, but are ill equipped for helping each other through the work of navigating who they truly are and who they are expected to be in a particular place.

Framing urban youth as neoindigenous, and understanding that the urban youth experience is deeply connected to the indigenous experience, provides teachers with a very different worldview when working with youth. From this new vantage point, teachers can see, access, and utilize tools for teaching urban youth. An understanding of neoindigineity allows educators to go beyond what they physically see when working with urban youth, and attend to the relationship between place and space.

If we are truly interested in transforming schools and meeting the needs of urban youth of color who are the most disenfranchised within them, educators must create safe and trusting environments that are respectful of students’ culture. Teaching the neoindigenous requires recognition of the spaces in which they reside, and an understanding of how to see, enter into, and draw from these spaces.

Reality pedagogy is an approach to teaching and learning that has a primary goal of meeting each student on his or her own cultural and emotional turf. It focuses on making the local experiences of the student visible and creating contexts where there is a role reversal of sorts that positions the student as the expert in his or her own teaching and learning, and the teacher as the learner. It posits that while the teacher is the person charged with delivering the content, the student is the person who shapes how best to teach that content. Together, the teacher and students co-construct the

...more

Instead of seeing the students as equal to their cultural identity, a reality pedagogue sees students as individuals who are influenced by their cultural identity.

reality pedagogy provides educators with a mechanism for developing approaches to teaching that meet the specific needs of the students sitting in front of them.

culture circle—where adults who were learning to read and write came together in an informal learning space and used their unique ways of speaking to become literate by sharing their understandings of the world and their place within it.

Cogens are simple conversations between the teacher and their students with a goal of co-creating/generating plans of action for improving the classroom.

neoindigenous practices during performances (and is most evident during the cypher), is that there is only “one mic.” This means that only one person has the floor at any given time. Others may support or affirm, but only one person at a time serves as speaker.

These studies confirm that employing indigenous and neoindigenous youth knowledge is the key to teaching neoindigenous people. I argue that additionally, the optimal way for youth language and experience to be used as a teaching tool involves having the youth themselves do the teaching. For this to happen, students have to be seen as teachers. By this I mean that students in traditional K–12 schools have to be viewed as partners with the adults who are officially charged with the delivery of content and be seen/named/treated as fellow teachers or coteachers.

How successful the teacher is in the classroom is directly related to how successful the teacher thinks the students can be. Teachers limit themselves and their students when they put caps on what their students can achieve.

urban youth as neoindigenous, Dr. Emdin situates students as members of a historically oppressed group, who are routinely educated for compliance.

reality pedagogy. He challenges us to meet “each student on his or her own cultural and emotional turf.”

the student is positioned as “the expert in his or her own teaching and learning,” co-constructing the classroom with the teacher.