Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 16 - June 19, 2020

short, Katzenbach v. McClung demonstrated that by the second half of the twentieth century, no restaurant could operate in the United States without engaging in interstate commerce—whether it wanted to or not.

social and historical context of this decision. Why, I asked myself, had white Alabamians considered it acceptable to eat food that had been prepared and served by black hands, but inappropriate to eat that same food sitting beside black diners?

Hale reconciles this paradox by explaining racial segregation as a cultural system that privileges whites as consumers in an increasingly consumer-based society. Segregation

Hale addresses segregation as a cultural system that involves all public spaces, including railroads, theaters, and mass media, in the modernizing and urbanizing South.

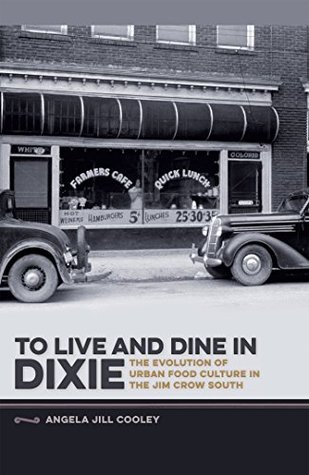

This book explores these issues of consumer equality and expanding national markets. It tells the story of food culture in the modern and urbanizing South.

In urban areas African Americans had the opportunity to dine out, operate eateries, and purchase, prepare, and serve commercialized food in a manner that depended more on socioeconomic status and less on race.

Whites often applied the language of impurity (such as “dirty”) to African Americans as a rhetorical justification for Jim Crow.

But in the South, the white middle class conflated food purity with racial purity and used notions of cleanliness to reassert the antebellum racial order that urbanization and consumerism undermined.

Eating out became a key feature of American food consumption after World War II.

When middle-class people took control of the regional food culture at home and in public, they began to define food practices according to race. In the cities, white middle-class women especially worried over the degeneration of the white race because lower-class whites often worked and lived in degrading conditions. They also desired to reassert white supremacy in an era when middle-class African Americans were succeeding compared to working-class whites.

Cooking methods based in an agrarian past and passed down through oral instruction and experience were giving way to new practices propelled by modernity and consumerism and dependent on scientific knowledge and technological advancement.

The “New South” also implies an emerging modern food culture whereby women learned to cook from experts in the field, administered their kitchens with scientific precision and businesslike efficiency, used written recipes, embraced new foods, and purchased technologically advanced products and appliances.

Although only an elite few would have had enslaved help in the kitchen, many turn-of-the-century white, middle-class women interpreted antebellum kitchens as “mammy’s” space—an area of black authority.

Civil authorities often sought to regulate, obstruct, or even shut down these operations. In the twentieth century, urban and town governments imposed specific licensing requirements for eating places. Such regulations reflected the importance that white authorities attributed to food, the Progressive concern for health and approval of government regulation, and white southern anxiety over the purity of the white body.

“blind tiger,” a term used to describe a lower-class establishment that sold illegal liquor.

miscegenation

Although more organized than most other communities, especially in the beginning, Nashville’s sit-in experience was typical. Students gathered at the First Baptist Church, which had served for more than a year as the site of Lawson’s workshops and would continue to serve as a civil rights headquarters in the city. Students dressed in their nicest clothes. Lewis wore the light blue suit he had purchased for his high school graduation, which he recalls would become a “trademark of sorts for me in the years to come.”