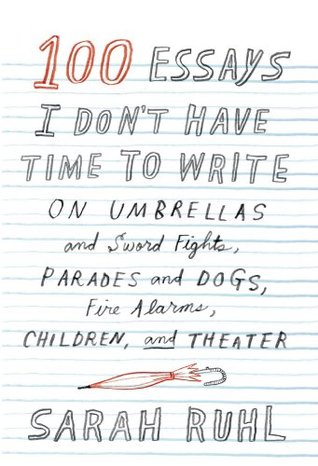

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Sarah Ruhl

Read between

February 22 - March 4, 2021

terms of moral identification and cleansing, comedy seems to be more philosophically virginal terrain.

the ethical comedy might teach us to embrace ordinary efforts to overcome folly over and above the tragic impulse, and to laugh at ourselves even as we weep for others.

worry is that if plays (in order to be high art) ought not to be too funny, or not funny in a certain way, because it cheapens their aesthetic status, then theater is relegated to the mode of ballet or opera—neither of which is funny, and both of which are historical.

plays have their roots in vaudeville as much as they have their roots in Passion plays, then their roots are cut off when laughter is viewed as cheap. We theater lovers

How wonderful that theater transcends language! But what kind of theater transcends language? And what does this mean for the future of the straight play on Broadway?

How is that possible? To make something out of words and ultimately the words don’t matter? You are writing language that will not be remembered; most likely, it will be a visual moment that is remembered. You

I thought, The age of experience is truly over; we are entering the age of commentary. Everyone at the event was busy texting everyone else at the event, and a general lack of presence was the consequence. What will constitute the quality of an event in the theater in the future, and how can we hope to enter eventness in the age of commentary?

look more often on non-American faces, or on faces that have waited in line for bread. Forbearance, cousin of dignity, sister of patience … Patience is no longer a virtue in this country, I’m afraid. We’ve made it into a vice.

waiting is lost, then will all the unconscious processes that take place during waiting get lost? And then might we see the death of the unconscious and the death of culture?

Erik Satie

And so with the theater: every night when a curtain comes down, a world dies. The world of present relation dies, and one mourns the end by applauding.

The basic structure of Noh drama is: a person meets a ghost, dances with a ghost, recognizes the ghost. The ghost leaves. The End. It is difficult for Westerners to see this as deep structure. But from a Buddhist perspective, it is the structure. To recognize impermanence, to see the self as an illusion, to grapple with leave-taking—this is one of the structural alternatives to the Crucifixion, to the wound at the center, the scapegoat.

Many Western traditions pin the arts against mortality; we try to make something that will abide, something made of stone, not butter. And yet theater has at the core of its practice the repetition of transience. We take something intricate and lovely and feed it not to the monkeys, but to each other.

fish in the living room aquarium. Tzipora starts combing my hair out. Her combing is gentler than my husband’s, and it makes me want to cry to think a stranger would be willing to do this for me (for a hundred dollars). It’s almost impossible to comb your own hair for lice when you have long hair.

realize that the rhythm at Tzipora’s house feels familiar to me, the great systole and diastole of work and children, the revelation of finding a sentence in the midst of chaos not unlike the joy of finding a buried nit. My kids come back from the fish tank, claiming they’re starving. Tzipora gives each of them a spoonful of peanut butter and sprinkles some baking powder on my head.

So, you thought you wanted to observe life? Motherhood shakes her head, clenches her fists, and demands, No, you must live

76. Mothers on stage

Mary Tyrone.

Or that the experience is tellable, but no one wants to see it. Mothers aren’t meant to have points of view. They are pages, ciphers for their sons and daughters to write their lives on. But I chafe at this notion that motherhood is unwritable.

mothers writing. What will the great roles for mothers be? Can motherhood be pressed into dramatic form? Do mothers wish to write about their experience of the little world of children, or when they are not in the little world, do they wish to think and write about other things?

Perhaps because, often, the demands of motherhood seem divorced from the demands of writing, and I can see both imagination and motherhood in this dilapidated velvet stool.

And this particular knot seems to be one for the peculiar class demographic of Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique—that is to say, women who have some choice about working or staying home.

On a daily basis, for the parent, the eye never rests. The eye is always on two stories, unfolding at once. Two protagonists. One child climbs a chair; one reaches for an electrical outlet. One invents a new word while the other is inventing a new gesture. You cannot watch one story unfolding, then another. You cannot fall in love with one protagonist, and then another. You must fall in love with two protagonists at once. The eye looks everywhere at once, the stories unfold at once, and the heart must expand doubly.

Brown University.

found in Paula’s approach to playwriting a great deal of pleasure and a great deal of play.

stammered, “This town is playing the Passion play year after year, but the guy who always has to play Pontius Pilate wants to play the role of Jesus, played by his cousin?” I remember that time slowed down as Paula looked at me in her uncanny way and said, “I think you should write that play.”

When I reflect on all the things Paula taught me—among them, Aristotelian form, non-Aristotelian form, bravery, stick-to-itiveness, how to write a play in forty-eight hours, how to write stage directions that are both impossible to stage and possible to stage—the greatest of these is love. Love for the art form, love for fellow writers, and love for the world.

This was the house that Paula had taken me and two other graduate students to years earlier. She had told us to go out on the deck, look at the view of the Atlantic Ocean, and say to ourselves, This is what playwriting can buy.

So, back to the abstract question: is playwriting teachable? Of course it’s not teachable. And of course it is teachable. It is as teachable as any other art form, in which we are dependent on a shared history and on our teachers for a sense of form, inspiration, and example; but we are dependent on ourselves alone for our subject matter, our private discipline, our wild fancies, our dreams.

In this model of development, the play is born bad. It exists to be reformed and bettered by the church (the institutional theater). The play is also unclean because it is a bastard child, since it is the issue of a single parent and the imagination, which has no flesh. It needs another parent, the church, to become clean. Baptism will hopefully come from a good review, without which the play is also unclean and destined for Limbo.

need you to ask: is the play too clear? Is it predictable? Is this play big enough? Is it about something that matters? Conversely, is this play small enough? And if the play’s subject matter is the size of a button, is it written with enough love and formal precision that the button matters?

We need you to remind us to make hard cuts and not fall in love with our own language when our plays are too long. We

Sometimes I think children make good dramaturgs because they are not terribly serious and their boredom mechanism is finely tuned. That is to say, they are bored by plays that aren’t theatrical, and we know they are bored because they scream.

Writing a play means that the author is often collaborating with invisible or dead

couple of exceptions to this rule: the Goodman Theatre has a dedicated room for the writer called the August Wilson Room, with a large desk. Arena Stage and the Public Theater are now giving health insurance to writers and making office space available for them. Playwrights Horizons has a writer in residence, Dan LeFranc. But generally, as ensemble theater disappears and theater artists become more nomadic, institutions become more still, more corporate, more steady.

we moved indoors and showed indoor subject matter. But the continued lack of a ceiling in the theater created, I might argue, a primordial connection with what used to be the sky; light poured in, and one understood that a room wasn’t really a room, but had a connection to some ancient playing space, by some ancient rocks.

Perhaps we don’t have storms in our plays so much anymore because our plays don’t take place out of doors so much anymore. But I think we also don’t have many storms in our plays because of a larger dramaturgical preoccupation with characters learning lessons that make emotions rational. And

somehow the use of storms on stage became symbolic rather than a mirror of nature when theater moved indoors. Why?

the irrational is relegated to the world of the symbolic rather than the mimetic, though life certainly seems irrational much of the time.

wake of a tsunami, what has happened? Water. Why has it happened? Water. What of justice? Water. Why anything? Because water.

If the world might well be an illusion (as the Buddhists say), then theater is definitely an illusion. And if theater is definitely an illusion, how sad to record real crickets so that they sound like fake crickets pretending to be real. If one’s goal is to reveal what we think of as the world to be an illusion, then false exits and crickets won’t serve.

the sound of crickets makes us feel that the night is more real on stage, it is more real with reference to a real night elsewhere, somewhere else recorded, someone else’s memory of a cricket-drenched childhood, someone else’s shorthand for night.

I am aware of the grandness of the arch and the seeming impermeability between the watcher and the watched, yet all that is required to burst through the illusion is to slip behind a curtain and use the facilities.

how quickly they are punctured: between the sick and the well, between the state of being alive and being, well, dead—where the divide seems absolute but the crossing is as swift and simple as passing behind a curtain.