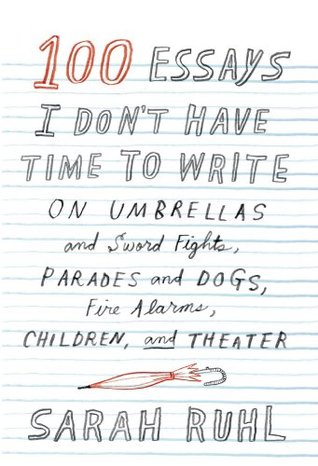

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Sarah Ruhl

Read between

February 22 - March 4, 2021

When I looked at theater and parenthood, I saw only war, competing loyalties,

and I thought my writing life was over. There were times when it felt as though

right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow. And then I could breathe. I could investigate the pauses.

Cosmology is brought low by the temporary shelter

But our primal bloodlust still seems to require a good fight on stage. It’s one thing to fight with our bodies and

we all know guns are fake on stage, so there is no real fear. Conversely,

Theatrical death by gun trumped death by language; gun wounds are final, they do not inspire soliloquies.

And if all actors were trained combatants, how would it affect our writing? Would our writing grow more teeth? More muscle? More blood?

are about the loss of one individual soul? The tragic perspective privileges one person over the continuity of the system, whereas comedies (which often end in marriage)

is perhaps more interesting to think about why we are in a land of the perpetual present, with no action having happened or about to happen. It is happening,

More event and more nouns, and less becoming out of time.

And what titles make people want to come to the theater and why do people want to come to the theater anyway and would people come to untitled works or would they be too hard to list in the newspaper?

Structure implies subtraction or repression; without the taking away or the hiding, there is everything, or formlessness.

Different plays have different shapes—spheres, rectangles, wavy lines, and of course the ever-discussed and ubiquitous arc.

Aristotle thought form was natural, but he thought the natural form was always an arc.

what has your character learned, how has she changed, what is her journey? All of these questions belong to a morality play.

The state of having a first and last name is a cultural practice closely aligned to patriarchy, land rights, and the individuation of the self, some would say the illusion of the self.

Mostly, this all-important choice goes unremarked upon, as it is by and large assumed that plays will have people.

And so it might be worth going back to first principles once in a while and wondering, sitting before the blank page, if one wants to people one’s play with people … or with devils, fairies, furies, and stones.

And I do believe that thinking is an overrated medium for achieving thought.

then the contribution of the playwright is not necessarily the story itself but the way the story is told, word for word.

But a writer’s special purview and intimate power is how a word follows a word.

to be the only person in the room who should know which word should follow which word, or (in Virginia Woolf’s words) how a voice answers a voice.

It is a different kind of listening, to listen to how the phrase unfolds as opposed to listening only to how the story unfolds.

playwriting will no longer be considered an art form if we are deprived of the paint—

Are we imitating life when we do not know the future? Or, in another sense, are we imitating life when we do know the future—that we will all die one day? And is it important to imitate life? How do we know what we

began: the secret happened not on stage, which, in a sense, makes it more real.

One might argue that by creating a reality that precedes the fictional world, we actually make the illusion less real because there is less power in the watching of

present. I believe, however, that very often the drama of the present moment needs no justification, and therefore no recourse to the past.

rather than experiencing the present. The mystery lies elsewhere. In contemporary drama, when the drama hinges on revelation of plot, the secret acquires both more and less significance than it actually has.

Vogel explains that alternatives to Aristotelian forms include: circular form (see La Ronde), backward form (Artist Descending a Staircase or Betrayal), repetitive form (Waiting for Godot), associative form (see all of Shakespeare’s work, in particular his romances), and what Vogel calls synthetic fragment, where two different time periods can coexist (Angels in America or Top Girls).

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, he begins, “Let me begin to tell of forms changed.” His emphasis, in terms of story, is on transformation, rather than a scene of conflict or rational cause and effect.

political escapism. That is another matter.) Still, I would argue that at the level of the story we crave transformation as much as we crave verisimilitude. Perhaps Ovidian form is not taught at universities as a genuine narrative form because it is very hard to teach the art of transformation.

The dialectic between the architect and the poet in modern dramaturgy reminds me of the old dialectic between morality and mystery plays. The morality plays had a clear moral for Everyman; the mystery plays (like the Passion) had an emotional effect harder to cognitively capture.

have never had much patience with separating genres into distinct categories. Maybe that is because I long for the time when we sat all day in the sun and laughed for a while, then wept while masked actors wailed,

Today, I stand with the mathematician. But the mathematician, while an expert in ignorance, also believed firmly and enthusiastically in the concept of progress.

We must constantly go back to go forward. And theater cannot believe in absolute knowledge, because usually two or three characters are talking and they usually believe two or three different things, making knowledge a relative proposition.

But the importance of knowing nothing is underrated.

“The only words that count in the play are those that at first seemed useless …

examine it carefully, and it will be borne home to you that this is the only one that the soul can listen to … for here alone is it the soul that is being addressed.”

to say, the interior of a person rather than the interior of a living room. As our plays culturally become more and more about the indoors—living rooms, bedrooms, and offices—are they also increasingly about the exteriors of people?

Put the bad poetry in the mouths of outlandish characters. It might make the bad poetry funny instead of sad.

If we trained playwrights’ ears rather than their parabolic sensibilities (that is to say, their ability to make an arc), what would our plays look and sound like?

where do we put all the asymmetrical people? The asymmetrical stories? Where do we put the crooked people? The people with one leg, lazy eyes, crooked grins? Do we write plays for them? Do we make theaters for them? If symmetry is beauty but life is asymmetrical, then how can art imitate life with an expression of formal beauty that is also true?