More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Saul had wondered whether to warn him about the dangers of looking for data to fit one’s theory, and decided that was akin to advising a deep-sea diver that it was a bit wet out.

He’d nearly died for his country a great deal too often; if that country was as grateful as it claimed to be, it could demonstrate that by leaving him alone.

One thing was for certain: Saul didn’t intend to dissuade Major Peabody from his researches. He wanted to meet Randolph Glyde again. He had questions.

“Amazingly, I don’t consider efficiency the sole and only good.”

“Let’s not play the fool. You want my name, and Jo Caldwell’s gifts, and Captain Barnaby and Mr. Isaacs as weapons. You may not have any of them. And don’t try to bribe me with your penny-ante offices again or I will take it poorly.”

“Not to tell you your business,” Sam said, “and I realise this may seem an extreme measure, and very much outside your area of expertise...” “What are you suggesting?” Sam grinned. “Have you considered talking to him?”

People create poetry and mustard gas. We invent gods and monsters and gods that might as well be monsters. We act with extraordinary grace and unfathomable cruelty. We’re so terribly intelligent, and dreadfully easy to fool.

He couldn’t imagine what he would say to this sophisticated, superior man. He’d have had the confidence once, and the desire, but he wanted something else now, something far harder to find than a quick suck in a back alley. He wanted his belief back. He wanted to know the things he’d thought he had—love, liking, companionship, and trust—could be real.

He wanted the touch of fingers, and a sympathetic voice, and someone with whom to laugh, or talk, or be silent. He wanted to know that someone thought well of him again; to feel for someone in return. And for the first time in years, he found himself believing that one day he might. It didn’t make him happy. It hurt like hell, like the agony of blood returning to a long-numbed limb, but, Saul realised, the painful prospect of hoping again was better than the dull knowledge he never would.

The aching need and want and vulnerability that Randolph recognised too well, as though whatever strings he plucked in Lazenby resonated in his own chest.

Randolph felt intensely visible, as though he could be seen for miles. As though Saul could see everything of him.

“Oh, well. When one expects terrible things to happen for long enough, it’s almost a relief when they do.”

“Really, dear chap, if we were permitted to conduct our business without fear or shame or gaol, would you have been sneaking secretly out, or would you have been in your bunk with a charming sergeant, or writing letters to the boy you left behind?”

“I didn’t start to speak against those orders until, what, September 1915, and then only to my family, quietly. It was already too late. The generals understood the scale of the weapon they had; they weren’t going to let it go unused. Some arcanists were drunk on power, and many more were too caught up to stop, and an awful lot of us knew it was catastrophic, but we believed in those simple rules. It’s so much easier to obey orders. It’s not much fun to think.”

We could have stood together across the battle lines and said no, this weapon is too great, the damage will be incalculable.

Tell me more about what if, Saul, tell me more about playing your part in catastrophe. The veil is hanging in tatters because we obeyed orders, three-quarters of England’s occultists are dead, and now two of London’s most vital protections depend on a stupid sod who’s let himself get trapped into being eternally two miles from Swaffham fucking Prior.

“How in blazes do you know about Cambridgeshire’s prevailing winds?” Randolph demanded, sounding somewhat affronted. “They’re always worth noting. They shape landscape and human behaviour. The world changes when the wind does.”

“I suppose that matters.” Saul’s tone suggested he didn’t suppose anything of the sort.

And he couldn’t stop this, wouldn’t if he could, because Theresa knew her business, and Camlet Moat needed a Walker. No matter what that did to Saul, already chewed up and spat out by one war, being dragged into another, and both times by a kiss.

Saul had to bite back a sharp remark—evidently all Randolph’s acquaintance shared his reluctance to answer a damned question—but he waited patiently until the Vicar returned with a sealed envelope.

Randolph had angular, slanted handwriting, more beautiful than legible, which didn’t surprise Saul at all.

“If you want answers, Randolph will give them to you.” Isaacs made an indescribable noise. Barney looked round, grinning again. “All right, perhaps he won’t. But I’ll take you to him so he can fail to give them in person. All right?”

Randolph wouldn’t have admitted he was waiting for a knock at the door. He was, however, hovering irritably in his sitting room not doing anything while the knock failed to come, and when it finally sounded he had to prevent himself from running. He checked his hair in the mirror instead, smoothing it to sleekness, and went to open the door.

“If it were up to me I should beg to discover—I think you said the crooks of your knees in particular? I’m fascinated by that. I want to see you in the light instead of the dark. I want to know how you look when you come. I imagine you look like an angel in pain, and I want quite desperately to see if I’m right.”

His back should have been—was—lovely. The wings of shoulderblades, the curved line of the spine, the irresistible swell of arse, with that dip of muscle to either side that you found in men who used their legs as God intended—although, that said, surely God actually intended Saul’s legs to be wrapped around Randolph’s hips; he was positive they’d fit.

“But if you are prepared to...let us say, to risk matters becoming complicated, I wish you would.” “I should love to complicate matters with you and see how we go,” Saul said.

Even if he didn’t have a hell of a job on, he’s not... He thought of sleek, prowling, predatory Randolph, carrying the words and scars of an ancient god. He’s not domesticated, Saul concluded, and nodded at his reflection with determination.

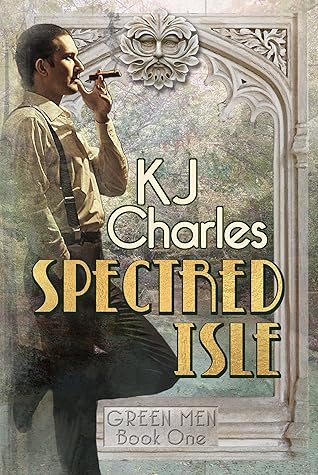

Think of it this way: there is an ancient duty to protect the land and its people. The Green Men carry out that duty, and that role can’t be taken, or given, at a whim.

It was huge, and he wasn’t sure why. He’d loved the stories, but that wasn’t it. It was the possibility; the knowledge that men like him had found each other for whole lives, not stolen hours.

He stood as though his pinstripes and position made him untouchable. One saw that a great deal with those who had found employment in sending other people to war; they hadn’t had the civilisation trained out of them.