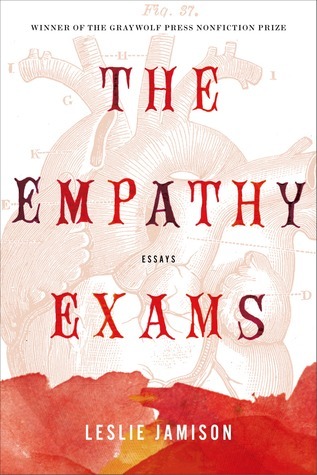

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Other students seem to understand that empathy is always perched precariously between gift and invasion.

Empathy isn’t just remembering to say that must really be hard—it’s figuring out how to bring difficulty into the light so it can be seen at all. Empathy isn’t just listening, it’s asking the questions whose answers need to be listened to. Empathy requires inquiry as much as imagination. Empathy requires knowing you know nothing. Empathy means acknowledging a horizon of context that extends perpetually beyond what you can see: an old woman’s gonorrhea is connected to her guilt is connected to her marriage is connected to her children is connected to the days when she was a child. All this is

...more

Empathy comes from the Greek empatheia—em (into) and pathos (feeling)—a penetration, a kind of travel. It suggests you enter another person’s pain as you’d enter another country, through immigration and customs, border crossing by way of query: What grows where you are? What are the laws? What animals graze there?

I remember wanting Dave to be inside the choice with me but also feeling possessive of what was happening. I needed him to understand he would never live this choice like I was going to live it. This was the double blade of how I felt about anything that hurt: I wanted someone else to feel it with me, and also I wanted it entirely for myself.

Empathy isn’t just something that happens to us—a meteor shower of synapses firing across the brain—it’s also a choice we make: to pay attention, to extend ourselves. It’s made of exertion, that dowdier cousin of impulse. Sometimes we care for another because we know we should, or because it’s asked for, but this doesn’t make our caring hollow. The act of choosing simply means we’ve committed ourselves to a set of behaviors greater than the sum of our individual inclinations: I will listen to his sadness, even when I’m deep in my own. To say going through the motions—this isn’t reduction so

...more

This confession of effort chafes against the notion that empathy should always rise unbidden, that genuine means the same thing as unwilled, that intentionality is the enemy of love. But I believe in intention and I believe in work. I believe in waking up in the middle of the night and packing our bags and leaving our worst selves for our better ones.

This is the grand fiction of tourism, that bringing our bodies somewhere draws that place closer to us, or we to it. It’s a quick fix of empathy.

Scholar Graham Huggan defines “exoticism” as an experience that “posits the lure of difference while protecting its practitioners from close involvement.” You’re in the hood but you aren’t—it rolls by your windows, a perfect panorama of itself. We don’t do drive-bys. You just drive by.

“Being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country,” writes Susan Sontag, “is a quintessential modern experience.” Part of what feels strange about this tour is that you’re assuming the posture of a tourist—How many people have died here? How do the boys come of age?—but you are only eighteen miles from where you grew up.

“Photographs objectify,” Sontag writes, “they turn an event or person into something that can be possessed.”

We may have turned the wounded woman into a kind of goddess, romanticized her illness and idealized her suffering, but that doesn’t mean she doesn’t happen. Women still have wounds: broken hearts and broken bones and broken lungs. How do we talk about these wounds without glamorizing them?

The moment we start talking about wounded women, we risk transforming their suffering from an aspect of the female experience into an element of the female constitution—perhaps its finest, frailest consummation.

People say cutters are just doing it for the attention, but why does “just” apply? A cry for attention is positioned as the ultimate crime, clutching or trivial—as if “attention” were inherently a selfish thing to want. But isn’t wanting attention one of the most fundamental traits of being human—and isn’t granting it one of the most important gifts we can ever give?

hating on cutters insists desperately upon our capacity for choice. People want to believe in self-improvement—it’s an American ethos, pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps—and here we have the equivalent of affective downward mobility: cutting as a failure to feel better, as deliberately going on a kind of sympathetic welfare—taking some shortcut to the street cred of pain without actually feeling it.

some news is bigger news than other news. War is bigger news than a girl having mixed feelings about the way some guy fucked her and didn’t call. But I don’t believe in a finite economy of empathy; I happen to think that paying attention yields as much as it taxes. You learn to start seeing.