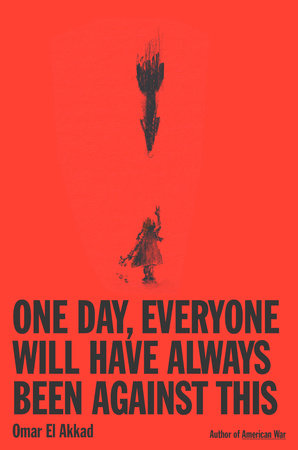

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 6 - October 13, 2025

It is a hallmark of failing societies, I’ve learned, this requirement that one always be in possession of a valid reason to exist.

Rules, conventions, morals, reality itself: all exist so long as their existence is convenient to the preservation of power. Otherwise, they, like all else, are expendable.

One of the hallmarks of Western liberalism is an assumption, in hindsight, of virtuous resistance as the only polite expectation of people on the receiving end of colonialism. While the terrible thing is happening—while the land is still being stolen and the natives still being killed—any form of opposition is terroristic and must be crushed for the sake of civilization. But decades, centuries later, when enough of the land has been stolen and enough of the natives killed, it is safe enough to venerate resistance in hindsight.

We are all governed by chance. We are all subjects of distance.

Whose nonexistence is necessary to the self-conception of this place, and how uncontrollable is the rage whenever that nonexistence is violated?

In the unfree world, the free world isn’t a place or a policy or a way of living; it’s a negation. National anthems and military flyovers and little flag lapel pins are all well and good, but for a life stunted by a particular kind of repression, the driving force will never be toward something better, but away from something worse. The harbor never as safe as the water is cold.

It was a bloodbath, orchestrated by exactly the kind of entity that thrives in the absence of anything resembling a future.

barbarians instigate and the civilized are forced to respond. The starting point of history can always be shifted,

Once far enough removed, everyone will be properly aghast that any of this was allowed to happen. But for now, it’s just so much safer to look away, to keep one’s head down, periodically checking on the balance of polite society to see if it is not too troublesome yet to state what to the conscience was never unclear.

Whatever mainstream Western liberalism is—and I have no useful definition of it beyond something at its core transactional, centered on the magnanimous, enlightened image of the self and the dissonant belief that empathizing with the plight of the faraway oppressed is compatible with benefiting from the systems that oppress them—it subscribes to this calculus. People go to see the president in the White House for what they know is only a meaningless photo op and yet, in the hopes of getting him to see, to do something, anything, they show him pictures of the mangled bodies of children. It

...more

This is an account of a fracture, a breaking away from the notion that the polite, Western liberal ever stood for anything at all. —

They come to the Indigenous population eradicated to make way for what would become the most powerful nation on earth, and to the Black population forced in chains to build it, severed from home such that, as James Baldwin said, every subsequent generation’s search for lineage arrives, inevitably, not at a nation or a community, but a bill of sale. And at every moment of arrival the details and the body count may differ, but in the marrow there is always a commonality: an ambitious, upright, pragmatic voice saying, Just for a moment, for the greater good, cease to believe that this particular

...more

What has happened, for all the future bloodshed it will prompt, will be remembered as the moment millions of people looked at the West, the rules-based order, the shell of modern liberalism and the capitalistic thing it serves, and said: I want nothing to do with this. Here, then, is an account of an ending.

the earliest days, in the chaos that precedes systemic annihilation, it is not what the party deemed most malicious has actually done that matters, but rather what it is believed capable of doing.

I’m sure it’s not the case that every editor of every major publication in the West doesn’t give a damn about all those inconvenient Brown people who keep getting killed and maimed by the thousands. But to never see these people in daily life, to never converse with them outside the bounds of interrogation, to never have reason to consider them human in any social sense—these things bleed into the story, or the absence of story. The afflicted don’t need comforting, they need what the comfortable have always had. —

A woman’s leg amputated, without anesthesia, the surgery conducted on a kitchen table. A boy holding his father’s shoe, screaming. A girl whose jaw has been torn off. A child, still in diapers, pulled out of the tents after the firebombing, his head severed from his body. Is there distance great enough, to be free of this? To be made clean?

And it occurs to me then, maybe for the first time in my life, that when Rambo leveled that small Washington town, or when Hunter S. Thompson made the cop chase him for miles along the desert highway just for the hell of it, it was never just an expression of ballsiness or rebellion or righteous anything. What the men who’d lived or dreamed up these stories understood was that the plausibility of such transgression depended on who the system being rebelled against was made to serve. Narrative power, maybe all power, was never about flaunting the rules, yelling at a cop, making trouble—it was

...more

A hard ceiling for some, no floor for others.

And then following the attacks, when Israeli defense minister Yoav Gallant says Israel is fighting “human animals,” it is not a statement of belief so much as permission. When those dying are deemed human enough to warrant discussion, discussion must be had. When they’re deemed nonhuman, discussion becomes offensive, an affront to civility.

For millions of Westerners this will always prove true. But for millions more it will not. In moments such as these, when the lies are so glaring and the bodies so many, millions will come to understand that there is no such thing as “those people.” Instinctively this will be known to those who have seen it before, who have seen their land or labor stolen, their people killed, and know the voracity of violent taking. Those who learned not to forget the Latin American death squads, the Vietnamese and Cambodian and Laotian villages turned to ash, the Congolese rubber then and Congolese coltan

...more

It is a reminder that the Democratic Party’s relationship with progressivism so often ends at the lawn sign: Proclaim support for this minority group or that. Hang a rainbow flag one month a year from some White House window. Most important, remind everyone at every turn of how much worse the alternative would be.

Against such hollow gesturing, even the most unhinged Republican will always be able to say: Look, these people have no interest in your suffering, only in empty gestures; I’ll do away with gestures, and make the right people suffer. It is an astoundingly effective technique, but would not be if the leadership of the Democratic Party had come to realize that sloganeering without concrete action means nothing.

Of course the Republicans would be worse. What the mainstream Democrat seems incapable of accepting is that, for an even remotely functioning conscience, there exists a point beyond which relative harm can no longer offset absolute evil.

The moral component of history, the most necessary component, is simply a single question, asked over and over again: When it mattered, who sided with justice and who sided with power? What makes moments such as this one so dangerous, so clarifying, is that one way or another everyone is forced to answer.

When the past is past, the dead will be found to not have partaken in their own killing. The families huddled in the corridors of the hospital will not have tied their hands behind their backs, lined themselves against the wall, shot themselves in the heads, and then hopped into mass graves of their own volition. The prisoners in the torture camps will not have penetrated themselves with electric rods. The children will not have pulled their own limbs out and strewn them all over the makeshift soccer pitch. The babies will not have chosen starvation. When the past is past. But for now, who’s

...more

I nod; I think about what Neil Sheehan once wrote in A Bright Shining Lie, about the difference between British and American approaches to empire—that the former felt compelled to civilize those they considered savage, a personal calling of sorts, a point of pride. The latter, on the other hand, had no use for any such notion. A strange thing, to be here, in this place, this moment, watching both costumes of empire thrown on at once.

Language is never sufficient. There is not enough of it to make a true mirror of living. In this way, the soothing or afflictive effect of the stories we tell is not in whether we select the right words but in our proximity to what the right words might be. This is not some abstraction, but a very real expression of power—the privilege of describing a thing vaguely, incompletely, dishonestly, is inseparable from the privilege of looking away.

It may as well be the case that there exist two entirely different languages for the depiction of violence against victims of empire and victims of empire. Victims of empire, those who belong, those for whom we weep, are murdered, subjected to horror, their killers butchers and terrorists and savages. The rage every one of us should feel whenever an innocent human being is killed, the overwhelming sense that we have failed, collectively, that there is a rot in the way we have chosen to live, is present here, as it should be, as it always should be. Victims of empire aren’t murdered. Their

...more

spineless headlines, but they serve a very real purpose. It is a direct line of consequence from buildings that mysteriously collapse and lives that mysteriously end to the well-meaning liberal who, weaned on such framing, can shrug their shoulders and say, Yes, it’s all so very sad, but you know, it’s all so very complicated. Some things are complicated. Some things have been complicated.

The Bush- and Obama-era practice of labeling just about any man killed by the U.S. military as a terrorist until proven otherwise is one of the most pernicious policies to come of the post-9/11 years, and for good reason. It doubly defiles the dead, first killing then imposing upon them a designation they are no longer around to refute. It also renders them untouchable in polite society. Should a drone vaporize some nameless soul on the other side of the planet, who among us wants to make a fuss? What if it turns out they were a terrorist? What if the default accusation proves true, and we by

...more

It is generally the case that people are most zealously motivated by the worst plausible thing that could happen to them. For some, the worst plausible thing might be the ending of their bloodline in a missile strike. Their entire lives turned to rubble and all of it preemptively justified in the name of fighting terrorists who are terrorists by default on account of having been killed. For others, the worst plausible thing is being yelled at.

There is, and has been for decades, a version of this phantom reality imposed on the Palestinian people, one in which they left their land willingly and were never expelled, never terrorized into movement. One in which, as Golda Meir stated and so many Israeli politicians have echoed since, there was no such thing as Palestinians. One in which Palestinian identity, if it did exist, was meaningless, and certainly conferred no rights. One in which these nonpeople were nonetheless treated well by the government and institutions that now rule over them, given good laborer jobs and sometimes even

...more

To preserve the values of the civilized world, it is necessary to set fire to a library. To blow up a mosque. To incinerate olive trees. To dress up in the lingerie of women who fled and then take pictures. To level universities. To loot jewelry, art, banks, food. To arrest children for picking vegetables. To shoot children for throwing stones. To parade the captured in their underwear. To break a man’s teeth and shove a toilet brush in his mouth. To let combat dogs loose on a man with Down syndrome and then leave him to die. Otherwise, the uncivilized world might win.

Over and over, the justification for all this—the secrecy and the censorship and the treatment of prisoners outside the realm of what the country’s foundational legal principles would ever allow—is justified by the threat these prisoners are said to represent.

If they didn’t hate the West before decades of their lives were taken from them, mustn’t they hate it now? What is the statute of limitations on resentment, on rage, on revenge?

He is forced in that moment to confront the reality that so much of the American self-image demands a narrative in which his country plays the role of the rebel, the resistance, when at the same time every shred of contemporary evidence around him leads to the conclusion that, by scope and scale and purpose of violence, this country is clearly the empire.

Anyone who buys into both the narrative of American rebelliousness and the reality of American authority understands that both have been created to serve them. The man in the action movie looks one way, the man the cops just shot in a traffic stop another.

In time there will be findings of genocide. There will be warrants issued, even. The structures of international law, undermined at every turn, will nonetheless attempt to operate as if law were an evenly allotted thing. As though criminality remains criminal even when the powerful support, bankroll, or commit the crime.

There is an impulse in moments like this to appeal to self-interest. To say: These horrors you are allowing to happen, they will come to your doorstep one day; to repeat the famous phrase about who they came for first and who they’ll come for next. But this appeal cannot, in matter of fact, work. If the people well served by a system that condones such butchery ever truly believed the same butchery could one day be inflicted on them, they’d tear the system down tomorrow. And anyway, by the time such a thing happens, the rest of us will already be dead.

No, there is no terrible thing coming for you in some distant future, but know that a terrible thing is happening to you now. You are being asked to kill off a part of you that would otherwise scream in opposition to injustice. You are being asked to dismantle the machinery of a functioning conscience. Who cares if diplomatic expediency prefers you shrug away the sight of dismembered children? Who cares if great distance from the bloodstained middle allows obliviousness. Forget pity, forget even the dead if you must, but at least fight against the theft of your soul.

But for the most part it’s just a constant trickle of reminders of one’s place in the hierarchy—and it is precisely because of this that it becomes so tempting to just shut up, let what’s going to happen happen to those people over there and then, when it’s done, ease into whatever opinion the people whose approval matters deem acceptable.

Because sometimes the powerful commit or condone or bankroll acts of unspeakable evil, and any institution that prioritizes cashing the checks over calling out the evil is no longer an arts organization. It’s a reputation-laundering firm with a well-read board.

this is where the poets will interject they will say: show, dont tell but that assumes most people can see.

The literary critic Northrop Frye once said all art is metaphor, and a metaphor is the grammatical definition of insanity. What art does is meet us at the site of our insanity, our derangement, the plainly irrational mechanics of what it means to be human. There comes from this, then, at least a working definition of a soul: one’s capacity to sit with the mysteries of a thing that cannot in any rational way be understood—only felt, only moved through. And sometimes that thing is so grotesque—what we do to one another so grotesque—that sitting with it feels an affront to the notion of art as a

...more

It is a source of great confusion first, then growing rage, among establishment Democrats that there might exist a sizable group of people in this country who quite simply cannot condone a real, ongoing genocide, no matter how much worse an alternative ruling party may be or do. This stance boggles a particular kind of liberal mind because such a conception of political affairs, applied with any regularity, forces the establishment to stand for something.

It is an admirable thing, in a politics possessed of a moral floor, to believe one can change the system from the inside, that with enough respectful prodding the establishment can be made to bend, like that famous arc, toward justice. But when, after decades of such thinking, decades of respectful prodding, the condition one arrives at is reticent acceptance of genocide, is it not at least worth considering that you are not changing the system nearly as much as the system is changing you?

Once again, the party’s supporters react to these demonstrations by chanting “Four more years, four more years,” which by now can no longer be described as simply ghoulish. There is instead a kind of mechanical fear laced in it, a sense among these people, as there has been a sense among all people at all times on whom the judgment of future historians has started to dawn, that they have stepped too far into complicity with something evil.

And it may seem now like it’s someone else’s children, but there’s no such thing as someone else’s children.

The problem with fixating on the abyss into which one’s opponent has descended while simultaneously digging one’s own is that, eventually, it gets too dark to tell the difference.

After two decades of destruction in Iraq and Afghanistan laundered through the silencing power of the term, it is tempting to make the argument that “terrorism” as a societal designation (meaning something that goes beyond the realm of legal terminology and into the realm of what we are willing to allow our societies to do and to become) is applied almost exclusively to Brown people. When a white man kills dozens of people in a concert or a synagogue or a school, it’s a crime. A hate crime, sometimes. But terrorism requires a distance between state and perpetrator wide enough to fit a

...more