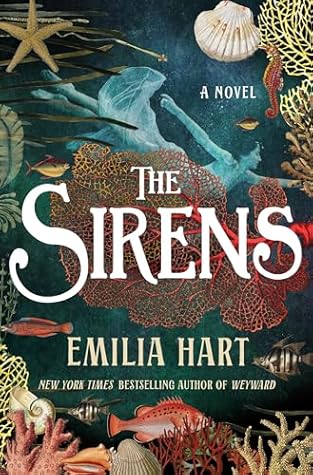

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In 1788, a fleet of eleven British ships landed on a shore almost ten thousand miles from England. The ships carried convicts whom the overburdened British prison system could no longer hold.

The First Australians, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, had thrived on the land for millennia before the arrival of those ships. It is estimated that over 250 languages—reflecting distinct nations with distinct cultures—were spoken in Australia prior to 1788.

Following 1788, First Nations peoples were subject to racist policies that aimed to “assimilate” them into white Australian society, an attempt to deprive them of their language and culture as well as their land. The effects of this are still felt today.

I would encourage you to seek out their stories. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, accessible at aiatsis.gov.au, is a good place to start.

Strangled. Her hands on his neck, the bulge of his eyes. She’d been strangling him. He sits up in bed, switches on a lamp. She bucks away from it like an animal.

Had she wanted to hurt Ben—to kill him, even—after what he’d done to her? Or had it been the dream, which lingers still like a bad taste in her mouth—the gnaw of fear, that primal need to fight, to survive?

It’s funny, the way some cases are forgotten, yet others live on in the public consciousness, the victims somehow immortal. Of course, the mystery itself—an unsolved puzzle, luring hacks and sleuths—is part of it.

“She’s a merrow,” Eliza said. “From the tír fo thuinn, the land beneath the waves. Just like in Mam’s story.”

For the first time, Mary noticed what Eliza must have always known, that a voice had valleys and crags, telling you of sadness or delight. You could almost feel it under your fingers, like it was land. This was how her sister knew things before they were said. The secret hurts and joys.

“Humans are born to storytelling,” Da used to say. “Does the goat tell stories? The blackbird, or the sheep? No. Sure it is God’s gift to us and us alone.”

Over the years, Da’s anger became Mary’s own. She locked her memories of her mother deep inside her heart. It was easier, she learned, to be angry than to be sad.

Now, I don’t know what to think. Maybe Max is right. Maybe there is some kind of rational explanation, some way that it all makes sense. But another, louder part of me feels like something is wrong, like my parents are keeping something from me. And the more I try to ignore that feeling, to swallow it down, the more it grows and grows, swelling like a parasite in my gut.

With this awakening, there’d been something else, too. A new awareness of her power. Freed from her prior inhibitions—from the compulsion to be nice, to be a good girl—she’d become something she could never have imagined being. She’d become … dangerous.

Most people just want an easy life. It’s unsettling when someone starts pulling apart the stories we’ve stitched together, the things we tell ourselves for comfort.

In a buried room of her mind, there is a recognition that the sea is calming her, is slowing the pound of her heart. The nearness of the water is a balm. Why is it that her body seeks out the thing that would hurt it?

Capture. It’s the perfect word, isn’t it? You paint someone and it’s like you own them, like you’ve taken their soul from their body and put it right there on the canvas.

Lucy wonders now if she’s spent her entire life distracting herself from the reality that there were too many gaps in the story of her family. A hollowness where the truth ought to be.

How long has she been sitting here? Her breathing grows panicked, shallow, as she scrabbles for details. But then she remembers. Everything she believed about her life is a lie.

The man who found Baby Hope at Devil’s Lookout and offered her to his wife, as if she was some treasure he’d dredged up; a pearl or an abalone shell. And Jess is Baby Hope. Which means Jess is not her sister. All these years, her family has been nothing more than a story. A collage of half-truths and lies.

Lucy thinks, but doesn’t say, how intertwined those things are. Fear and desire. How one can become the other so easily. All it takes is the tightening of a hand on your wrist, your throat.

“I love you. Both of you. Please, remember that.” Lucy knows it’s true. She is loved, and so is Jess. Their parents left everything behind to protect her. But they also lied. Don’t read any more of that diary. What else are they hiding?

In the darkness, a pale form. The globe of the head, the amphibian curve of a spine. An ultrasound. The column of text on the left-hand side reads: 20 April 1999 Martin, Jessica

For months, she’d sat across the dinner table from her parents, knowing their secret and waiting for them to guess hers. The easiest way to lie to someone, she learned, is to lie to yourself.

“Where,” Jess tried, but her mouth was too dry to speak. She was thirsty, ever so thirsty. She licked her lips and tried again. “Where am I? Where is Lucy? Where is the baby?”

To tell Lucy now—it might destroy all those hopes and plans, all those dreams for the future. If Lucy knew that the story of her life was a lie, she might lose her passion for seeking the truth. And Jess couldn’t do it. She just couldn’t take that away from her.

She had asked Lucy to make a choice. But sometimes, there is no choice. There is only love.