More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

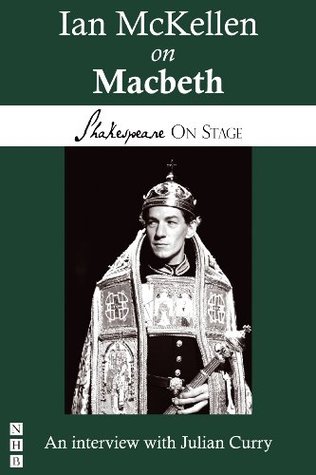

by

Ian McKellen

Read between

January 15 - February 23, 2025

But it’s almost as if Shakespeare thought that to be a warrior was to be fulfilled as a man, and yet he realises that the warriors themselves don’t feel fulfilled, they want more. I think he’s saying if you’re prepared to kill somebody, well, you’ve gone off the rails. And they make dreadful kings, all of them, these soldiers.

There’s an immediacy about soliloquies, which I think should always contain the possibility of the slight pause, the question mark, the raised eyebrow, inviting the audience to give their response.

And he psychs himself up as he must have done any number of times before going into battle. And you know, the pity of Macbeth is that he spends his life killing people – that’s his job and he’s brilliant at it. It’s what the state employs him to do. Is it any wonder that he can’t cope with being a civilian? He knows you can’t be a civilian and behave like a soldier. He’s trying to reconcile those two things. Soldiers kill. It’s what they are obliged to do. And the more they kill, the more successful they are, the more heroic. In civilian life, one mistaken murder can bring down horror and

...more

Macbeth is not an assassin. He is a professional soldier, warrior, athlete, who kills. It’s his job. This is not of that sort. And he is as conscience-stricken as any of us would be if we were killing somebody, not because they deserve to be killed but because we wanted them out of the way. What’s remarkable about this great man (and it is, as I said, a problem of the play) is that you don’t see him on the battlefield doing these things. You see him going in and causing the easiest death he’s ever accomplished in his life. The guy’s asleep. Put a hand over his mouth, he can’t speak, you kill

...more

Then suddenly ‘Whence is that knocking?’ No wonder it freaks him out. ‘How is’t with me, when every noise appals me?’ Me, Macbeth! Oh, he knows he’s betrayed himself. He already knows he’s on his own. She can help clear up the muck, the mess. But from there on their relationship is over.

(It’s going to be alright) Here let them lie Till famine and the ague eat them up. Were they not forc’d with those that should be ours, We might have met them dareful, beard to beard, And beat them backward home. (That’s what I used to do, that’s what I can do! But then – ) — What is that noise? — The Queen, my lord, is dead. ‘Oh, I see, oh, I see. It’s all over. She’s died, I’m going to die, we’re all going to die. This is nuts, this is nuts…’ And, I don’t know, he’s almost waiting for it to happen. He’s volatile.

I don’t know… ‘Tomorrow’… maybe that’s the word. ‘Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and – ’ (oh, fucking hell!) ‘ – tomorrow, / Creeps in…’ and he’s off! Where does that all come from? Well, that’s his future. What is the future? It’s ‘Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow’. I used to think when I was saying it, if you repeat a word often enough – ‘tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow’ – does it stop having any meaning? It must have been the first rap song! It ‘creeps in this petty pace from day to day…’ and I used to think ‘Tomorrow, today, and all our yesterdays’. So it’s about the future and

...more

But the death takes place offstage, which is presumably because Shakespeare wants the head brought back on. It’s not an easy thing to achieve, but in an ideal production it’s important. Macbeth has lived entirely through his head, or has tried to. It’s that head that’s been exploding, full of all these dreadful images and certainties and worries. And all he is at the end is the head. ‘Look at that, look at that! That’s where it all happened, that’s what the play has been about.’

Because it’s in so many of the plays, once those soldiers go into politics, they’ve had it. And the rest of us have had it. So it’s a mighty cautionary tale.

Shakespeare’s writing about a believable society of civil servants and soldiers and royalty, and if you think it’s just about a man in a kilt who doesn’t get on with his wife, you’re missing the point. The play is much more resonant than that. Imagine the despair at the end when young Malcolm stood there and said what he was going to do, with such clarity and lack of passion. This was the man who lied so convincingly to Macduff in the England scene, when he said he was acquainted with all the evils of the flesh [4.3]. He could describe them, he could imagine them vividly. And you think ‘Oh

...more

I don’t think there’s an optimistic ending to Macbeth at all. It’s chilling. There’s a chilling pause while you’re just invited to look at these frail human beings and think ‘Oh Christ…’