More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

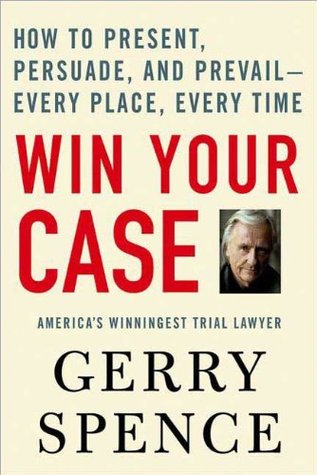

Gerry Spence

Started reading

June 16, 2022

After fifty years making my presentations in and out of the courtroom I’ve learned one thing for certain: It all begins with the person, with who each of us is. If we have no knowledge of who we are, if we have no insight into the self, if we have never heeded the admonition of the sages—“Know thyself”—we walk before the power persons (the jury, the board, the boss, the administrator) as a stranger to the self. And all of the participants at the presentation will remain as strangers to us as well.

When our uniqueness is fully discovered and launched, we are indomitable.

In high school and college we are educated in order to convert our unique beauty into spare parts for the system—the massive machine out there needs administrators, engineers, accountants, designers, computer experts, workers, and lawyers. Like all spare parts we must be uniform in order to fit smoothly into the machine without any disruption when an old part gives out.

Being different is an abysmal appellation, so some pierce their tongues, their navels, their ears, and whatever else, in order to become the same in their difference.

Your thumbprint is utterly individual to you. Why, then, can’t we understand that our very essence as persons, let us say our souls, is also unique among all other living human beings and among all those who shall ever in the future take a breath?

Jurors complain that the fancy talk of lawyers and experts flies over their heads. “Those big words,” they complain. “Why don’t they talk to us like human beings?” The truth is that those who make their presentations with words as long as an eighteen-wheeler are hiding something. Often big words hide incompetence. They also hide the presenter’s fear. But jurors and other decision makers feel put down, minimized by this flouting of a massive technical vocabulary that’s empty of caring and conviction. Big words often hide small minds.