More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

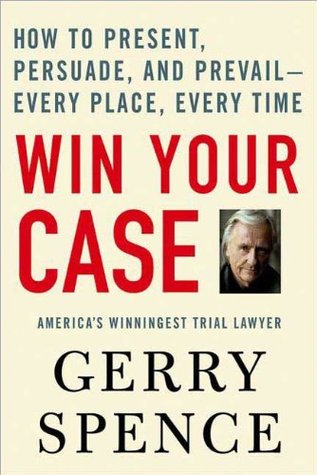

by

Gerry Spence

Read between

July 11 - November 7, 2025

Our method begins with the self. It demands that we tell the truth, even when it is painful. The method is based on the story and the storyteller.

As Atticus Finch, the fictional lawyer in To Kill a Mockingbird, said to his young daughter who had a penchant to do battle with her fists, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” We cannot understand human conduct without understanding others, and we cannot understand others without first becoming acquainted with ourselves.

A person’s power in the courtroom or the boardroom, and a salesperson’s ability to make the sale, emerges from his or her uniqueness.

If logic and reason, the hard, cold products of the mind, can be relied upon to deliver justice or produce the truth, how is it that these brain-heavy judges rarely agree? Five-to-four decisions are the rule, not the exception. Nearly half of the court must be unjust and wrong nearly half of the time. Each decision, whether the majority or minority, exudes logic and reason like the obfuscating ink from a jellyfish, and in language as opaque. The minority could have as easily become the decision of the court. At once we realize that logic, no matter how pretty and neat, that reason, no matter

...more

To move others we must first be moved. To persuade others, we must first be credible. To be credible we must tell the truth, and the truth always begins with our feelings.

Spontaneity is the key that unlocks the door of the listener, because that which is spontaneous is honest and is heard as honest. And if it is honest it convinces. If it is honest it moves the other to our side, to our way of thinking. If it is honest it wins. In the end, the product of spontaneity wins.

When we’re tied to our notes, or worse, when we’re frozen in the words of a memorized script, the sounds, the language, the whole dramatic movement is lost.

Listen to the anchor persons on the evening news—the placid smiles pasted on their otherwise dead faces, their lips forming the words, their eyes glued to the teleprompters. They tell us in their singsong voices about murders and rapes and unspeakable horrors of every description, and even, occasionally, of joy. We are unmoved. We hear about thousands killed or maimed in bombings across the world. Nothing happens. We go on eating our popcorn. The flow of blood may turn the rivers scarlet and the dead bodies may well lie bloating in the sun, but as they read, the anchor persons provide us

...more

In the same way as the late-night show host who was tied to his notes, I see lawyers in the courtroom tied to theirs. They have not heard a single answer of the witness. They have not heard any of the unspoken words of the witness. They have not been listening with either their own, two exterior ears and surely not with their third ear. As a consequence, the lawyer bumbles along and the examination usually goes nowhere. The witness is left in control, because the lawyer is controlled by his notes—filling the room with the sound of his voice that, as it were, signifies nothing.

Even after all these years, when I go into a courtroom I still feel fear. People’s lives and my career are in my hands. I’m afraid I’m going to fail. Indeed, now as an old man I am completing the circle of fear. I am as afraid as I was when I was a young man trying my first case. I am only better at admitting it. And the question for me

It is all right to be afraid. One cannot be brave without fear. Those young fools who love danger and feel no fear are only fools. Courage comes when we recognize our fear, face it, and hurl ourselves into the battle. I think of Captain Ahab, in Moby Dick, who said he wanted no men on his ship who were not afraid of the whale—which means that he didn’t want any fools around him. The line between courage and foolhardiness is narrow.

I see many deserving people deprived of justice because of these well-paid frauds—the horribly crippled children negligently injured in childbirth who can never walk or speak an intelligible word, the woman who will never see again because of an incompetent surgeon asleep at the switch, the hordes of injured who lose their right to justice because insurance companies have embraced these charlatans who, case after case, spread their malignant lies on innocent jurors. Their haughty pretenses and their venomous testimony (which they know is false) always angers me, sometimes to the precipitous

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

We also remember that the American juror usually favors the underdog. A gross display of power on one side attracts a leveling attitude on the part of the jurors. Many times, and for obvious reasons, I have gone to court alone to face a bevy of powerhouse lawyers on the other side. If I have a choice between putting together a team, one consisting of a half-dozen lawyers with all of their specialties and expertise on the one hand, or just me (and the jury)—in the end I may be on the winning team.

From my experience in the courts for over fifty years I can say that when we buy an insurance policy on our car or home, what we have really purchased is the right to sue the company for its failure to pay. The company involved will nearly always pay less than what is justly due, knowing full well that the shortfall is too small to warrant a suit against them.

What we really experienced in law school was a lobotomy of sorts, one that anesthetizes the law student against his emotions and attempts to reduce law to some sort of science, which, of course, is a bizarre notion, since, as we’ve seen, even the high court can’t agree on a single proposition of law, and justice is, at last, something felt, so that what is justice for one is unjust for another.

The problem still remains: When we sue a corporation we teach it nothing, because a corporation can learn nothing, feels nothing, and suffers nothing. If we want to sue because it is just, let us sue for our need. For the corporation, the justice we receive will be only an entry in some obscure account, probably in an office a thousand of miles away, the entry made by a bored employee without a name. But it is our justice and it belongs to us.

I rarely refer to notes in the courtroom. They are distracting and leave the appearance of someone who doesn’t know his case. When the president makes his speech he is aided with unseen teleprompters from which he reads his carefully prepared address. But the appearance is that he is speaking without notes and from the heart. I say that it is better to speak from the heart, even given the false starts and sometimes the mistakes or omissions. When we speak from notes we proceed from the eyes, to the brain, to the vocal cords, to the audience. That part of the brain that houses our deepest

...more

If we are to be successful in presenting our case we must not only discover its story, we must become good storytellers as well. Every trial, every presentation, every plea for change, every argument for justice is a story.

Danny’s story was made vivid and memorable because the lawyer put himself into the hide of Danny, tried to feel it as Danny felt it, and encouraged him to relive the experience by having him speak in the present tense. Most stories we hear from lawyers are poorly constructed previews of the story to come, previews that would not compel us to rush to the movie house.

I believe the value of a focus group is to learn how to better tell the story, and the best way to tell the story is always from the inside out. It’s hard to tell our story until we know it—that is, until we’ve felt it—heard it with our third ear, seen it with the eyes of our client, until we have been gripped by it in deep places, and have finally lived it. Only then are we ready to tell our story to the focus group—our objective, to learn even more: Have we told the whole story? What part did we omit? Were we blind to areas in the story that others readily saw? Sometimes we’re oblivious to

...more

Often people will ask what your case is about. Can you answer the question in a short paragraph? If you can’t, you haven’t discovered the story yet.

Why do we need a theme for our case? It usually contains the essence of our story—the quintessential statement that continues to emerge from out of the chaos of words, that redirects us to the cause when the arguments lead to other places and fuzz our focus. The theme speaks of the underlying morality of the case—what is right or what is wrong. It is the final argument in a single phrase.

Sharing. Each member of the group has had his or her own experience with failure and disappointment, with false promises and fraud. Each has had a set of experiences that, when told, will likely add another facet to the story. A part of every person is a part of us. And we have experienced a part of every experience of every other person. If we are told of a shipwreck in a hurricane, we have experienced our own near-collision with a truck in a blizzard. The galvanic experiences are the same. We are flooded with adrenaline. We gasp and load our lungs with air against the danger. Our hearts beat

...more

I always present my case as a story. The old saw, truth is stranger than fiction, holds here. The story must be truthful or else, as we have seen, the case will surely be lost. The beginning, the setup, as in nearly every movie, introduces us to the hero (our client) in ways that permit us to care about him. Then we experience the difficulty he is in, the conflict, and finally we map out for the jury the resolution, the ending we wish the jurors to adopt. In our hearts we all love to hear and to tell a good story. Stories, well told, are the engines by which we win.

Including, not excluding the jurors. Lawyers hire experts to help them determine which jurors to exclude from the jury. I’m more interested in which jurors to include. How does it feel to be questioned, when we know that the questioner, no matter how charming, is intending to expose whatever fact, whatever small secret he can pry from us in order to strike us from the jury? And who wants to be cross-examined? Nothing in this approach invites the prospective juror into the process, and that’s where we want him: with us. Moreover, since prospective jurors understand the game, they can play it as

...more

I begin with the proposition that everyone has an opinion, but everyone is basically fair. The questioning takes on the flavor of friends talking, accepting the other’s opinions and feelings with respect. It is not a manipulation or a strategy. It’s simply an attempt to be who we are with each other. I’ve finished many a voir dire examination not wanting to strike a single person from the original jury panel.

Step 5. Accept (and honor) the gifts the jury gives us. Remember, whatever answer the juror gives is a gift to us. It took courage for the juror to open up and tell us the truth about how he or she feels. The juror trusted us enough to tell us. We must honor that. And we need to thank him as we would any who have bestowed a gift on us.

I have often said that if I am given the opportunity to engage in an effective voir dire, that is, if I can open up the jurors to the issues in my case and create a trusting relationship with them, and if thereafter I can make an effective opening statement, the case is mostly won. First impressions of a case are hard to overcome. If our opening story is sound and honest and reveals the injustice for which we seek retribution, the picture it creates in the minds of the decision maker will be hard to erase. Indeed, research reveals that something like eighty-five percent of jurors make up their

...more

If there is a set of facts that is hurtful or embarrassing to my case I hasten to present it in my opening. I want the jury to know the facts against me. I want to expose what lurks beneath in order that the jurors will trust what lies on top. I never want the underside of my case revealed by my opponent. When that happens the jury’s trust vanishes like dew on a hot griddle. From the standpoint of a sale, nothing is more trust building than a salesman who will tell us about the weaknesses of his product.

What about facts that are in dispute? Let’s tell the jury that the facts are in dispute. Let’s tell them our position and our opponent’s and then explain why our position is better. What if there are hurtful facts that cannot be explained away? Let’s tell them that. There may be regrets that need be expressed, apologies made and shared with the jurors. But the overriding justice of the case still rests with our side.

But a polite, gentle, smiling response is so disarming. It is difficult for a judge to be too violent with a peaceful person in front of him. If we show no anger in return, none, the way is often easily cleared. In fact, a little good humor, nothing smart, will often work wonders. The lawyer who fights with the court is going to lose in this power struggle. Nothing is more intimidating to a judge than a lawyer who contests the judge’s power, and the judge will come down with all of his power to keep it.

As soon as I take a case I begin to correlate the opening statement with the witnesses that I will be calling to support it. As the witnesses’ anticipated testimony expands, or as new facts are discovered, I go back and work some more on the opening statement. By the time I walk into the courtroom to deliver my opening, I know the story so fully I could deliver it in my sleep. In fact, I have. Winning in the courtroom is not so much a reflection of the genius of the lawyer but of that lawyer’s preparation. Among the comments I have heard about my work in the courtroom, the one I most value is,

...more

“Where does this incident take place, Shirley?” “It’s an apartment complex on Bath Street.” “As you face the building from the street, tell us what this apartment house looks like?” “It’s a brick building with three stories—one front door. The bricks are smudged with a lot of smoke and grime. There’s graffiti under one window. Some of the windows on the third floor have no curtains over them, and some have cardboard to cover where panes of glass have been broken out.” If the witness can’t produce this kind of detail, then we have to go with the witness to the scene and point out all of the

...more

Preparing the witness for cross-examination. The prospect of our opponent’s cross-examination can be frightening. Nothing protects the witness against fear and anger better than preparation. The witness who takes the stand becomes the target. In many ways his function is that of the soldier on the front line. If the opponent can kill him it brings the war that much closer to an end. We are still barbarians who use words instead of swords. The courtroom becomes an arena of human struggle. But, if we understand the nature of the trial, we can prepare ourselves and our witness to survive and

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I tell the client it is proper to say, “I don’t know,” if the client doesn’t know. I say, “Don’t guess and don’t add anything that is unnecessary to give a full and honest answer. If you make a mistake, simply say you made a mistake. The truth is always the safe port, even when it hurts. Don’t be afraid of the cross-examination. I will be there to protect you against any improper questions. And one thing for sure. Be absolutely as fair and friendly to the cross-examiner as you are to me. Remember the three Cs.”

The need for the preparation of our client and all of our other witnesses is only too clear. The last words I say to my witness before I call my witness to the stand are, “When Mr. Jones gets up to cross-examine you, pretend that he is your friend, someone you can trust, a nice man who has to be gently straightened out on a few things. View him as one who is somewhat disadvantaged because he doesn’t know the truth of this case. I do not mean that you should patronize him. No. I mean that you should treat him kindly—as you would treat me if I made an error concerning your case.” Often this

...more

What is cross-examination? Cross-examination is simply storytelling in yet another form. Cross-examination is the method by which we tell our story to the jury through the adverse witness and, in the process, test the validity of the witness’s story against our own. The proper, standard cross-examination questions contain two parts: first a statement that forwards our story through that witness; for example—“No one, to your knowledge, Officer Jones, has been able to connect that gun to Mr. McIntosh, …” followed by the second part of every question, “isn’t that true?” Note again: the question

...more

The basic cross-examination. Once we’ve discovered the story that we want to tell through this witness, Deputy Brown, we can simply state it, sentence by sentence, with the question attached, “Isn’t that true?”

We have told our story a sentence at a time, adding only the words, “Isn’t that true?” It makes little difference what the witness answers, as long as our story is honest and based on the facts as we know them in the case, or on facts that can reasonably be deduced from the evidence already before the court. It is for the jury to determine which story is true:

As we have seen, the legitimate purpose of cross-examination is to test one’s bona fide theory of the case against the testimony given by the witness. The story of the witness and that of the cross-examiner will be laid against each other. Which story do we believe? The witness has told his story on direct examination. He is implacable, even hostile to the idea that the gun was planted. His story is pat. He has been well prepared. His story matches the police incident report. There’s little to grab hold of, and, if we can do nothing more than offer up questions that permit the witness to

...more

Our strategy will be to cross-examine the witness with what I call the “compassionate cross,” simply a cross-examination that takes into account that this witness is a decent, ordinary human being facing a moral dilemma. We want to understand him and, before the cross is ended, to speak for him in ways that he cannot speak for himself. The key is to understand what this police officer faces, and to present him to the jury as a man facing a dilemma from which he cannot extricate himself.

The open-ended question in cross-examination. The home of the leading question is, of course, cross-examination. We all know the old saw: Never ask a question on cross-examination to which you don’t know the answer. Insulate yourself from disaster by always leading. But if we pause to reflect we will soon recognize many a place where the open-ended question is called for.

She is now responding, as many witnesses do, as if we are trying to trap her. We have never changed our tone of complete courtesy—focused and factual. The change in her demeanor is actually startling. It’s not that she isn’t the grieving mother that she purports to be. She is. But she, like most witnesses, has begun to react defensively to the cross-examination. And the jury is seeing that the once untouchable witness is presenting herself as one who, indeed, can and should be cross-examined.

Passing the witness for cross-examination. Despite what I have said, there are those witnesses who ought not be cross-examined. Witnesses who merely establish foundation facts, witnesses who testify to matters not in dispute, who can offer nothing to otherwise support our case—these witnesses should be passed with a courteous, “No, questions, Mrs. Perkinson. Thank you for coming.” I see lawyers who believe it is their utter duty to cross-examine every witness who has ever walked into a courtroom. The examiner has reduced himself to a nitpicker—someone who soon wears out his welcome with the

...more

The ultimate power of cross-examination. If truth exists, and if it can be discovered, it will best be exposed in a well conceived cross-examination. Facts are more than mere words. They are imbedded with the demeanor of the speaker—his conviction, his forthrightness, his interest in the outcome of the case, his honor, his humanness, and his credibility. Although I have written about it here at length, cross-examination is just another form of storytelling, and, of course, listening with our third ear. If there be an art to it, it is the art of preparing, of listening, and, finally, of being a

...more

In the same way that I write out my opening, I also write every word of my closing. The argument has become fully embedded in me. Although I will take the notes to the podium, I will rarely refer to them. I have not memorized the argument. Instead, the argument has taken on a life of its own. It will direct me once I begin to speak. I will find myself giving arguments with words and supporting metaphors that I had never thought of—not until the very moment they are delivered to the jury. The argument, if it is unleashed, if it is trusted, will create itself. But it has been built and nourished

...more

Justice always comes up short.

We can immediately see that the specific facts of the case have not been repeated. They have been used as reference points in the argument. There may be further facts that should be argued that show that the defendant’s reconstruction expert is wrong, that he is a hired charlatan—whatever the evidence may be in that regard, but always, the facts are but ammunition for the argument and are never to be recounted in the form of witness summaries. But throughout the argument the tone will reflect our sense of ethical anger, and honestly delivered, our argument will infect the jury and create in

...more

On any jury there will be those individuals with whom we feel most comfortable and those with whom we feel more distant. So it is in every group of people. You can be sure that the mirror is at work here. If we feel distant to Mrs. Smith on the jury, it is very likely that she has the same feeling toward us. And we can very easily alienate her, because we are not going to speak as readily to her as to the other jurors who have shown their openness toward us. But if we do not talk specifically to each juror, the juror who has been by-passed will feel left out. And that juror will resent us. We

...more