More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

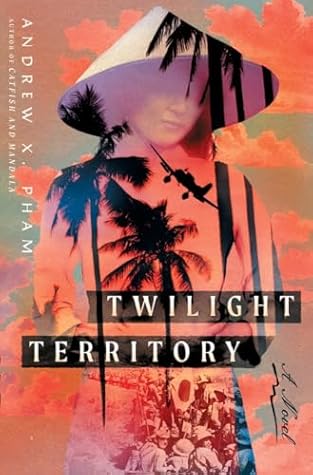

This novel is a work of fiction inspired by some events in the life of the author’s maternal grandmother.

“Indochina,” “Annam,” “Tonkin,” and “Cochinchina” are names coined by the French to delineate their colony without deference to the colonized.

Modern Vietnam comprises 54 ethnic groups, with the Viet (Khinh people) accounting for 87 percent of the population.

Tuyet remembered the first time she met Major Yamazaki Takeshi. An inauspicious day at the peak of the hot season of 1942. The late afternoon sun had slipped below the roofline, leaving the street in shadow. All day, the dragon-bone wind howled and showed no sign of abating. Hot and sandy, it was an unpredictable whirling thing that swept through once every few years and never brought anything good. It chafed the skin, infected eyes, and put grit in the teeth. It tore leaves and branches from trees, blew red dust into every nook and crevice.

Aunt Coi arranged a low table just inside the shopfront. “Slackers aren’t earners,” she said when Tuyet complained that the weather was too foul for business. Coi was forty-six years old, Tuyet twenty-eight. Coi was a diminutive woman with half-moon eyes. She had glossy black teeth, dyed for fashion as a teenager. Since Tuyet’s mother had passed away fifteen years earlier, Coi had been Tuyet’s mother, best friend, and confidante.

Their rented home was one half of a house, divided right down the middle by a bare brick wall, the living space consisting of three narrow adjoining rooms. The bedroom was in the middle between the kitchen in the rear and the shop, which faced the street. Ten removable planks, two meters tall, served as the door of the wide shopfront.

Along the side of the house, a strip of dirt was a well-tended vegetable garden with basil, chili peppers, mint bushes, tomato plants, trellises of bitter squash, and green beans.

Coi, Tuyet, and her two-year-old daughter, Anh, shared a divan in the bedroom. The only other furniture was a small dresser bought from the landlord. Coi’s twenty-two-year-old...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Recently, there had been a strong Japanese presence in the town since they took over the Phan Thiet airbase from the Vichy French government.

“Empty stomach teaches the knees to crawl.” Tuyet murmured her late mother’s favorite proverb.

“No truth more convincing than the lies one tells oneself,” Tuyet retorted.

Ha’s father, a village tailor, had committed suicide after he had gambled away their house and savings, leaving Coi and twelve-year-old Ha homeless and destitute.

Major Yamazaki Takeshi had arrived in Indochina two months earlier to take command of the Phan Thiet airbase. The post had been given as a reward for his service in the Second Sino-Japanese War, though he suspected it had more to do with him saving a general’s life. That act of bravery had wounded him in battle and put him in the hospital for multiple surgeries. He was still suffering from his injuries, but considering the easy life he was enjoying in the fishing town, he knew he would gladly save the general and be wounded all over again.

Takeshi jerked awake, dripping in a pool of sweat that had soured the bedsheet. His head throbbed, cheek clammy against the pillow. A swampy taste in his mouth. His throat dry, hoarse, his limbs leaden.

His left shoulder creaked, protesting his effort to rise. He fingered the scar between his nipple and collarbone. The bullet had punched through his left shoulder and out the front. Raising his elbow higher than his ears was painful. Shrapnel had mangled his right leg. A long-distance runner in his prime, he barely managed an ungainly jog with his stiff knee, which bent only halfway.

“If you really want to know more about this place, I’d like to invite you to dinner with some knowledgeable elders. If they become acquainted with you, things will go easier for me.” “That makes sense,” he said with a smile. “I am honored to accept your invitation.”

He had inherited his father’s vast plantations and branched out into business and manufacturing. His wealth and power would have continued to grow if it hadn’t been for his carnal appetites.

He was happy, and Tuyet found that she was too. It struck her as peculiar, in a pleasant way, that they had stepped out of reality this afternoon, here on an empty beach, wearing European clothes, eating Spanish food, sipping French wine. For a moment, she could imagine a world without war.

She ventured a personal question: “Do you miss your home?” He thought about it and replied, “A boy misses home; a man remembers it.” “And a woman?” “A woman makes a home.”

Sunset crept onto the beach. The calm, glittering surface of the sea yielded to twilight. Shadows stretched and twisted on the dunes. Wild colors swirled across the sky on the horizon, the smear of a brewing storm. The wind strengthened and brought his scent to her.

She was unaware that she suffered the universal hunger of orphans, a profound yearning to be loved, to be wanted. It rendered her vulnerable.

Le Jardin Rouge—the Red Garden—sat in the middle of Pasteur Avenue, east of downtown. It was a grand two-story mansion with white columns and steep rooflines, illuminated by a hundred red globe lanterns. In the garden of roses, bougainvillea, and wisteria filled with water fountains and gazebos, waiters in black velvet jackets served guests at tables covered in white linen. An ornate wrought-iron fence fronted the property. It was Saturday night, and luxury automobiles lined the road, still slick from the afternoon rain. Drivers milled about on the footpath, smoking, watching the arrival of

...more

Ly stepped out in a form-fitting violet gown, her hair fashionably coiled above her head. Tuyet followed in a sapphire-blue wraparound dress, a soft silk cut that flattered her petite stature. Her hair was twisted into a bun and pinned with ivory combs.

Tuyet sensed a dark tide rising. “Does this mean what I think it means?” “If you want peace, prepare for war,” Takeshi replied. She sighed, wishing it were not so.

Wherever we go, we take with us the scars and the karma we’ve earned.”

“Your men must be looking forward to getting back to Japan. Aren’t you eager to go home, too?” Yamazaki looked away. “Every man who goes to war takes it home with him. I’m in no hurry.”

At the Potsdam Conference in Germany in July 1945, the Allies had agreed that China should move more than one hundred fifty thousand troops into Vietnam to disarm the Japanese and control the country north of the sixteenth parallel. The underpaid, undernourished, and ill-disciplined Chinese troops looted and plundered from the northern border to Hanoi, wreaking further havoc on a country already devastated by Japanese occupation and famine.

After joining the Resistance, Yamazaki Takeshi participated in several Viet Minh engagements against French forces. In early November 1945, he visited his family at the safe house, located on a plantation in the highlands owned by a Viet Minh supporter. Satisfied that Tuyet, Coi, and the children were safe, he immersed himself in the cause of the Resistance.

Yamazaki chose the academy primarily because he did not want to face fellow Japanese in battle. By late 1945, the British-led coalition had pushed the Viet Minh into the remote countryside, effectively crushing the Resistance. Wrapping up the British campaign at the end of January 1946, General Gracey handed over the southern part of the country to the French general Jacques-Philippe Leclerc. Weeks later, the northern part of the country was traded to the French by Chinese generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, who had earlier vehemently opposed the recolonization of Vietnam.

With the French firmly in control, the nascent Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) quickly fell into disarray. Factions within DRV became polarized between the two leading groups, the Viet Minh and the Nationalists. The former was generally popular with the peasantry, the latter with the middle and upper classes.

From March to May 1946, hundreds of Nationalist leaders and organizers were summarily murdered, some killed in secret, others butchered in front of their families. Abandoned by the Americans, deceived by the Brits, and betrayed by the Japanese as well as the Chinese, the Viet Minh adopted Communist doctrines. In July 1946, temporarily allied with the French, Viet Minh troops attacked the Nationalists’ headquarters in Hanoi.

Viet Minh and French troops drove the remnants of the Nationalist army into China and into permanent defeat, killing tens of thousands. With the opposition groups eliminated, the Viet Minh faced the French alone.

A misunderstanding in Hai Phong resulted in Viet Minh militiamen killing twenty-three French soldiers. North of Hanoi, six French troops were killed days later. On November 23, 1946, the French retaliated by butchering more than six thou sand men, women, and children in a single day, bathing the streets of Hai Phong in blood.

Yamazaki yearned to be with his family. He quit his instructor position and volunteered for a mission in the south. He left Quang Ngai under new identity papers. Yamazaki was now Vo Van Ki, a language professor born in Saigon to a Vietnamese mother and a Japanese father. During his time at the academy, he had improved his Viet language skills so he could pass himself off as a native in simple exchanges.

Inspector Jacques Renier and his spy, Vo Phong, walked up to the door. A butler showed them through the spacious home to a wide veranda at the rear where the master usually greeted his daytime visitors.

Mopping his bald pate with a handkerchief, Renier asked the butler for his usual drink. There he stood, arms akimbo, scowling at the rose garden, his magnificent handlebar mustache twitching. He could barely contain his excitement at the first break in the Japanese case.

Renier wished he could find someone like Bui. After a year in Indochina, he remained a bachelor. His interest in women was minimal. Roughly twice a month when the biological urge arose, he visited the gentlemen’s spas to relieve the pressure. Once his needs were satisfied, he desired neither female conversation nor female attention. For thirty-five years, his late wife had provided all the companionship he needed, and he felt that hiring a companion now would defile her memory.

“Do your dreams tell you what the future holds for us?” “It doesn’t work like that. In hindsight, dreams unveil what I already know. In foresight, they show me the prominent thread of destiny.” “There is no choice, then.” “A fortuneteller once told me: ‘The lines not yet read can be rewritten.’ ” “What does that mean?” “What you want it to mean.”

He reached for her. She realized with a sharp pang that this was the pinnacle of their love. Life was uncertain. Danger lurked in darkness. It would never be so perfect again. In the trees, a lone cicada sang a shrill note. A chorus replied. Matsuo Bashoˉ’s lines rose like silvery bubbles from the dark depth of his mind: The cry of the cicada Gives us no sign That presently it will die

My father needs to bless his grandson. We can return when there is peace, when it’s safe. The longer we stay here, the harder it will be to leave. The fighting will only get worse.” “Someday, we’ll go. Someday.” Half promise, half evasion. A dose of desire, a fathom of fear. Not something she wanted to face. She curled into him, nestling her head in the crook of his neck to stem his sudden flight of fancy. Japan seemed so far away, foreign, unreal. She was afraid, she was selfish. It was not in her to leave friends and family. She was not ready. She could not imagine living in a foreign land.

Four months earlier, they had moved down from the mountain hut to this small village in a border area people called the Twilight Territory, a swath of land between the towns and the wilderness, controlled by neither the French nor the Resistance.

They had bought a small homestead consisting of a thatched bungalow, a few sheds, and a fruit orchard on the outskirts of the village. It was a temporary arrangement that allowed Coi to stay in touch with Ha. He shook his head. “I really don’t know what tomorrow will bring. Do you?” When Tuyet could not be truthful, she retreated into silence.

Despite all the hardships and heartbreak, they were still whole then. They had all that could be good and kind and sweet between two people. They were perfect in those final moments.

That was the art and the tragedy of dream-walking. One did not ask “what if” after reality had unfolded. It was not in the dream-walker’s lexicon. Things, events, parts of life played out like déjà vu. It had always been too late. They had been here before. It was inescapable.

A short soldier motioned with his weapon for Tuyet to join the group of captives waiting by the road. Coi stood up to follow her niece, but he pushed her back down saying she was too old. “Please, let me go in her place,” Coi said. “She has young children!” “Sit down and shut up, old woman,” he snapped and pushed Tuyet forward by her elbow. “Take care of the children, Auntie,” Tuyet called over her shoulder as the soldier roughly shoved her along.

Finally, the corporal replied, “Those in the truck are being taken to the garrison for work. Those people on foot are going to Crystal Creek to repair the bridge the Viet Minh destroyed last week. If you want to help them, bring food and clothes to the garrison or the workers’ camp at the creek.”

Looking back at the crowd, she did not see her aunt. In the field where the market had been, chaos prevailed: trampled fruits, smashed jars of pickles, mounds of white noodles souring in the sun. The butcher’s table had been turned upside down, pink heaps of innards and meat scattered in the grass, the hog’s head on its side with its beady eyes seeming to laugh at the mess. Cawing blackbirds descended on the remains, picking through the spoils, brazen like scavenging dogs. The convoy returned the way it had come, kicking up a cloud of dust.

At dawn, he woke the children, had them wash their faces, and told them to prepare for a mushroom hunt. Anh clapped her hands, for she loved spending time in the woods. The dogs danced in circles, infected with her excitement. Nunu, the calico cat who had come with the house, looked down from the kitchen shelf, yawned, and dismissed them with a flick of her tail.

Anh skipped after him, a woven basket riding on her hip, clutching a small paring knife in her hand. Seven years old, she fancied herself a princess in commoner disguise. She did not know how to joke or tease, but she had an endearing smile, a special skill with animals, and a prodigious memory for things that grabbed her interest, such as searching the woods for things to eat.

Anh squealed when she discovered a cluster of mushrooms and squatted to harvest them. Outraged by the intrusion, a koel bird scolded them from the branches of a fire-blossom tree.