More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

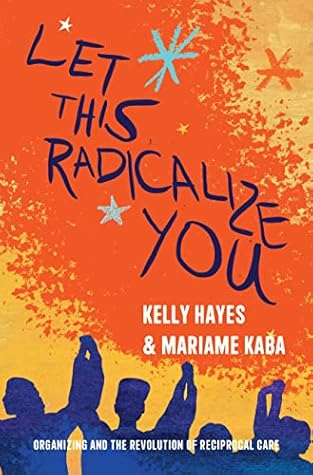

Kelly Hayes

Read between

February 7 - February 24, 2024

“Hope and grief can coexist,” Kelly and Mariame remind us, amid millions lost to the pandemic, amid rising fascism, amid many-sided attacks on our most basic bodily autonomies—“and if we wish to transform the world, we must learn to hold both simultaneously.”

“Let this radicalize you rather than lead you to despair.”

“The war that matters is the war against the imagination / all other wars are subsumed in it.”3

Mutual aid, of which defense committees are good examples, has the power to change our social relationships, to galvanize us into groups and communities that confront specific crises—and then move on to fight much broader battles.

fear alone doesn’t usually hold people’s attention, let alone inspire them to action. Similarly, social media bombards us with flashes of tragedy and injustice throughout our waking hours, but most of these stories do not widely reconfigure worldviews or provoke new action; they often prompt people to retweet and move on.

If spitting horrifying facts at people changed minds and built movements, we would have overthrown the capitalist system long ago, because the facts have always been on our side.

in a world where corporations and governments worldwide are poised to annihilate most life on Earth, we are made to believe that other disempowered people are the greatest danger we face.

As the unprecedented flourishing of mutual aid projects during the pandemic has demonstrated, many people respond to communal crisis with generosity and shared concern. The idea that disasters autogenerate panicked, aimlessly violent hordes of people who must be controlled with an iron fist is an authoritarian fever dream. While the powerful would have us believe that frightened people are always selfish and hypervigilant, cooperation and collaborative care are common human responses to disaster.

People across history have largely turned to one another for comfort, sustenance, and protection in moments of crisis. Acknowledging this truth threatens a social order built on the myth that we need authority to protect us from our own chaotic impulses in times of crisis. The state sees communal care as an ideological threat. This is why mutual aid movements are routinely targeted and undermined by the US government. Mutual aid projects are a manifestation of power that contradicts the state’s primary narrative about what it is, who we are, and whose purpose it ultimately serves.

that imprisoned people often defy the system by “refusing to abandon each other.”

As humans on Earth in these times, we are raised into a rigged game, traumatized by its violence, and coached to replicate its dynamics. We are surrounded by lies, illusions, and coercion. We are sold punishment as justice and annihilation as progress, and many people cannot imagine anything else. But just as we do not abandon people we love who are in crisis, we have not given up on humanity. We have witnessed transformation too often to dismiss its possibility, and we have an obligation to that possibility in individual lives and in larger groups of people.

In this society, the idea of “saving” people is a troubled one. Often, when people talk about saving others, they are talking about something coercive, like criminalization. Laws that criminalize sex workers and people who use illicit substances, for example, are often depicted as “saving” those people from harmful, depraved forces. In reality, the enforcement of such laws plunges people into a system that inflicts physical and sexual violence upon them, while also robbing them of our most finite resource—time. Some people view themselves as saving others by attempting to convert them to

...more

Our goal should be interdependence: to be part of a community where rescue is viewed not as exceptional but as something that we owe each other.

Having studied apocalyptic events across the course of human history, as well as the likely disaster scenarios of our time, Begley quashes notions of rugged individualism, insisting that “basic traits like kindness, fairness, and empathy” will be the basis of any sustainable, meaningful effort at collective survival—and as Begley stresses, we cannot survive alone.10

Why aren’t these narratives of spontaneous mutual aid more widely shared in mainstream culture? Perhaps it’s because a recognition of our collective capacity for care during a moment of chaos does not reinforce state hierarchy. It does not reinforce individualism or what the government ultimately wanted most out of the aftermath of 9/11: a greater allegiance to US militarism.

This is not the outcome the powerful are hoping for. They are relying on our cynicism, our divisions, and our despair, in addition to their mass apparatus of repression, to prevent us from cultivating a new way of living in relation to each other. To defy and defeat them, we must cultivate hope, belonging, care, and action.

The gutting of public education was geared toward the prevention of an “educated proletariat”—as a Reagan adviser once put it while denouncing free college8—and has robbed many young people of the opportunity to explore a great deal of history and literature and to develop a personal practice around that exploration.

By mimicking protest art, officials sought to refashion Black Lives Matter into a mainstream phenomenon—something that belonged to everyday people and politicians alike. After all, how could city officials be part of the problem if they were not only making the philosophical concession that Black lives mattered but also offering a public visual to affirm it? While some appreciated the murals, others regarded them as pandering gestures, often from officials who played key roles in perpetuating—and sanctioning—police violence.

The Defund the Police movement was challenging the order of things and would ultimately be blamed for the electoral losses of politicians who never embraced it, as well as for supposedly rising crime rates.

But under these definitions, the destruction of property is usually viewed as violent only if it disrupts profit or the maintenance of wealth. If food is destroyed because it cannot be sold while people go hungry, that is not considered violent under the norms of capitalism. If a person’s belongings are tossed on a sidewalk during an eviction and consequently destroyed, that is likewise not considered violent according to the norms of this society. Those destructive acts are part of the “order of things.”

In moments of unrest, it’s important to remember that, as Martin Luther King Jr. stated, there is no greater purveyor of violence in the world than the US government.

Defending people who’ve been incarcerated for acts the state deems violent is an essential act of antiviolence—challenging the vast harm perpetrated by the state itself.

Conditions that the state characterizes as “peaceful” are, in reality, quite violent.

Even as people experience the violence of poverty, the torture of imprisonment, the brutality of policing, the denial of health care, and many other violent functions of this system, we are told we are experiencing peace, so long as everyone is cooperating. When state actors refer to “peace,” they are really talking about order. And when they refer to “peaceful protest,” they are talking about cooperative protest that obediently stays within the lines drawn by the state. The more uncooperative you are, the more you will be accused of aggression and violence. It is therefore imperative that the

...more

Meanwhile, organizers campaigning to defund the police and redirect funds toward life-giving services are blamed for alleged spikes in violent crime, even though no correlation exists between defund efforts and crime rates.

Since 2016, 13 states have quietly enacted laws that increase criminal penalties for trespassing, damage, and interference with infrastructure sites such as oil refineries and pipelines. At least five more states have already introduced similar legislation this year.

The fact that these laws draw on national security legislation created in the wake of 9/11 is illustrative of two important facts: laws that supposedly target “terrorists” will always be used to target activists, and those who would interrupt systemic violence will in turn, be associated with violence by those who maintain the system.

In order to ward off surplus people and discourage migration, governments narrow migration routes to scenarios that will necessarily result in mass death. At least seven thousand migrants are believed to have died along the US–Mexico border from 1998 to 2017. More than thirty-three thousand migrants died at sea trying to enter Europe between 2000 and 2017. People who disrupt this cycle of violence are accused of human trafficking and smuggling because they chose to preserve life. This should not surprise us. When laws encode violence and law enforcers maintain it, those who attempt to prevent

...more

Klemp’s statement calls out the hypocrisy of governments that would obscure their own violence with symbolic gestures. From block-letter street murals to state-sanctioned awards that exceptionalize individual activists as “heroes” while death-making policies remain unchanged, we must reject the empty PR maneuvers of those who sustain the oppressions we struggle against.

State violence around the world is routinely dealt out in such a manner: the state reserves the right to overstep its own laws, and even when it subsequently acknowledges its mistakes, it has already subjected people to the indignity of arrest, deprived them of their liberty, or subjected them to other violence.

Kayali points out that under international law, Palestinians have the right to violently resist Israel’s unlawful occupation of Gaza, but she also cautions against placing an overemphasis on “structures of law and legality.” As Kayali told Kelly on Movement Memos in May 2021, as Israeli bombs were raining down on Gaza, “What this comes down to, in my mind, is kind of the omnipresence of neoliberalism and its tight grip on our framing of justice.”

Why write love poetry in a burning world? To train myself, in the midst of a burning world, to offer poems of love to a burning world.

Our oppressors rely on our hesitation to feel for one another. They rely on our suppression of empathy and grief and on the desensitization that often takes hold as a defense mechanism in the face of so much suffering. They are hoping that the battery of catastrophes we witness in real time will shorten our attention spans until the fallen are forgotten in the blink of an eye.

Together, we rise to deprive the monster of its simple story, and replace it with our own.

This practice of hope allows us to remain creative and strategic. It does not require us to deny the severity of our situation or detract from our practice of grief. To practice active hope, we do not need to believe that everything will work out in the end. We need only decide who we are choosing to be and how we are choosing to function in relation to the outcome we desire and abide by what those decisions demand of us.

This practice of hope does not guarantee any victories against long odds, but it does make those victories more possible. Hope, therefore, is not only a source of comfort to the afflicted but also a strategic imperative.

Memorials can also be biting or disruptive, and that, too, can be a source of healing for participants. As politicians and corporations push us to accept a society that does not grieve mass death, our grief and stories of the dead can function as resistance.

Acts of rebellious grief can take many shapes, but all are a rejection of mass death and an insistence on the humanity of those who have passed.

As James Baldwin emphasized at the close of his book Nothing Personal, “The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.”26

The forces that oppress us may compete and make war with one another, but when it comes to maintaining the order of capitalism, and the hierarchy of white supremacy, they collaborate and work together based on their death-making and eliminationist shared interests. Oppressed people, on the other hand, often demand ideological alignment or even affinity when seeking to interrupt or upend structural violence. This tendency lends an advantage to the powerful that is not easily overcome.

These destructive dynamics are perpetuated in part by a culture of martyrdom embedded in movement work. The idea that we should be willing to die for what we believe in resonates with many organizers and lends itself to the notion that we should be willing to work ourselves to death. This can lead us to make commitments that exceed our capacity.

1. What resources exist so I can better educate myself? 2. Who’s already doing work around this injustice? 3. Do I have the capacity to offer concrete support and help to them? 4. How can I be constructive?