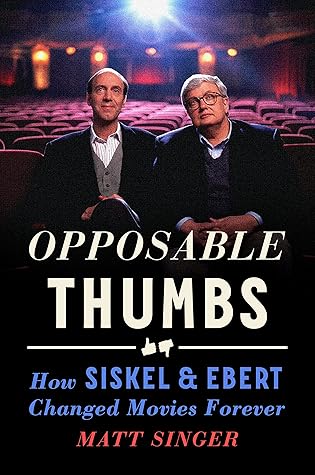

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Matt Singer

Read between

January 7 - January 11, 2024

A few months before the Opening Soon pilot premiered on WTTW, Ebert had become the first film critic in history to win the Pulitzer Prize for criticism. A film critic wouldn’t win the award again for another twenty-eight years.

“There’s something conversational about his writing. It just reads like a person talking. He was very good at that.”

Seeing a great movie is still the great pleasure of my job. But then it’s an added pleasure to be able to interact with the movie: to think about it, to talk about it, to write about it. That, too, is a lot of fun. —Gene Siskel

The Great Movie Test: If you rewatch a classic over and over, do you get new things out of it each time? If yes, then it is a truly great film.

Today, movies are one of a near-limitless array of viewing options including television shows, YouTube clips, and TikTok videos. But in the late 1960s and early ’70s, movies weren’t just popular, they were important. They dominated the cultural conversation. They were the most influential and widely consumed art form on the planet.

“We don’t want to see the small screen become the primary viewing vehicle for pictures,” Siskel said on one of these “Top 10 Cassettes” episodes. “It has to be the big screen, because if people start to say, ‘I’ll wait [to see it] at home,’ then you’ll never see The Right Stuff made. They’ll never make a big-screen epic. They’ll make these intense personal dramas which don’t suffer as much, like Terms of Endearment, when you see them on a small screen. And that would be a disaster for the movie business. It wouldn’t be the movies. It would be TV.”

“By turning criticism into a debate, by turning it into a conversation, Siskel and Ebert found two things,” says Robert Thompson, the director of the Bleier Center for Television and Popular Culture at Syracuse University. “One: that people found it interesting to hear people talk about movies, and two: arguing about movies seriously, which is presumably what we do whenever we walk out of the theater. They carved out that space. That was so groundbreaking.”

“To say that a movie or a song contains something is not to make a meaningful statement about it, except simply to say what it contains,” Ebert explained. “I think you have to look a little further into tone, mood, message, purpose, context, and origin in order to understand whether a movie or a song has a message that’s worthwhile or whether it’s simply negative and destructive. And that’s something I think that Senator Dole and other people who have joined his cause have not been willing to do.”

“The sad fact,” Ebert wrote, “is that film criticism, serious or popular, good or bad, printed or on TV, has precious little power in the face of a national publicity juggernaut for a clever mass-market entertainment.”

Lucas was even more prophetic. In the same year that the World Wide Web was first invented, the architect of Star Wars essentially anticipated the world of streaming movies, and how it would change the theatrical landscape forever, telling Ebert, “I think the marketplace will shift dramatically. I think certain kinds of movies will be made directly for the home and certain kinds of movies will be made for theater presentation . . . the larger, more spectacular ones will end up in the theater and the more personal ones will end up on the screen.”

Roger Ebert wrote more reviews in 2012 than he had in any other year in his near half century as a film critic: 306.