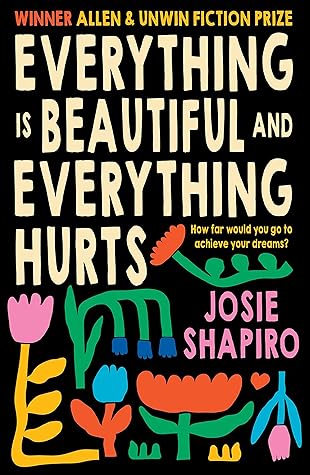

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 19 - December 27, 2023

raggedy Canterbury shorts,

I know that I’m not a leader. I prefer to hunt.

IT WAS A WET SATURDAY in September 2000, the rain falling in thick silver sheets. The first daffodils had opened only a few days earlier, and their bright-yellow trumpets now lay flat, collapsed under the ceaseless onslaught.

Corned beef. Silverside. I hated it — I called it ‘suicide’.

An advertisement for PAK’nSAVE turned the room yellow, and I left without saying goodnight.

Under the covers her body looked like hills, a series of curves and undulations, so different from how she’d looked under that same duvet as a child. I still found it awe-inspiring how our bodies could change simply with the passing of time.

It was disgusting. I was disgusting.

I relax my torso, keep my neck soft, my shoulders down. My legs swing and thump and push. I am dancing, I am flying, I am beauty.

I wasn’t sure if it was any better at home than it was at school.

Is that proof of my strength or my stupidity? The lies I’ve told to get here, the hurt that others have caused me: none of it matters right now.

He smelled good — like leather and something sweet. I looked at him, careful not to stare. He was beautiful. Right then, all I wanted was for him to feel that way about me.

With no one there to see, I could almost convince myself that I wasn’t crying.

Marathons are like life. A lot of it will be shit, more of it than you thought you could tolerate. But I bet you, when it’s over, you’ll say, ‘Goddamn. Can I do that again?’

The sun hovers above the horizon, sending a channel of light down the harbour to the bridge, and I feel the light on my face. What a marvellous thing this is, being alive.

If only I could forget what he’d said about my body. You need to change, he’d said, you aren’t beautiful like this. I looked at his eyes, the long lashes, his body: there was nothing about him I would dare suggest be different.

The battle is inside your mind. You have to be stronger than anything the world can throw at you.

‘What was that all about?’ Emma asked when he’d gone. ‘Nothing.’ But I wasn’t sure, and wished my mum was there. This was growing up: I was on my own.

I was young, bullish and angry, and part of me might have been looking for danger.

Above the water a gannet soars on the breeze, its whiteness stark against the black-green of the volcanic peak. I smile. We’re both flying, at peace in the moment, born to move and be free.

I knew my mum loved me, even when I didn’t understand why she did.

The beauty of the world continued just the same, unconcerned with me.

IT WAS COLD INSIDE THE MRI. I didn’t understand how it worked. The tunnel seemed inert, yet it was gathering information from inside my body, releasing the secrets held inside, the ones I’d thought would remain hidden.

It was comforting, as if someone was close by, and I was not all alone, inside a machine that threatened to end it all.

What I was doing was foul — and it was simultaneously delicious, a release from all the self-loathing. Cutting myself was disgusting — but I was disgusting too. My body had betrayed me. It had let me down in so many ways — too big, too small, too touched, too imperfect, too fractured. The red lines on my skin felt like a message to others: it’s okay, the message said, to find me repulsive, because I do too.

I drove to Bethells for a swim. The beach was packed, but I didn’t mind the crowds. It was so much like home out there, the black sand and wildness of the west coast. The Tasman Sea, rough and untamed, stretched out as though to the end of the world.

I couldn’t understand how siblings — once so close, almost like one person — could grow apart the way they did, almost as though they were strangers.

I tried to convince myself that I didn’t need my father, his love or his approval. I was kidding myself, though. I’ll never stop wanting that.

I know its maunga, the trails winding up the grassy slopes. I know its harbours, the Waitematā, the Manukau, the golden sheltered bays of the North Shore, the unrestrained ferocity of the West Coast beaches. I know its roads over motorways, its public toilets, its broken footpaths. The pockets of bush, the playgrounds, the strips of shops in Ponsonby, Onehunga, Browns Bay, Howick, Māngere Bridge. I know its limits, I know its expanse. Now it is my home.

Being lighter hadn’t helped me; it had done nothing but weaken my bones. Now, when my period came, the bloom of crimson was a sign that all was working as it should, that I was strong and capable of absolutely anything.

I’m intimate with time. I understand the nature of a second, of a minute, of an hour, how they can metamorphose in my mind. A second feels like a minute, a month feels like a week. Time is elastic, stretching to fit around your movement, your emotions.

minutes can feel like hours, like days, the agony of moving forwards seemingly neverending.

When I grieve my mother, or feel rage at my father, minutes I’d rather feel as seconds drag out into weeks, months,

I want the freedom to run in the dark hills.

I clenched my teeth. Fucking men.

It had been a dream run, all alone on the tarmac, the sunrise a reward for me and only me.

In the moment of silence between us I heard the booming of the waves, and I thought of the roads, my roads, empty and waiting for my footsteps.

When things get hard, don’t question your worth. Don’t let other people’s opinions about your running steal your joy.