More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

English schools, the moment they depart from the conventional track, are oases of strangeness and comedy, and it is tempting to linger.

What went wrong? I think I know now. A bookish attempt to coerce life into a closer resemblance to literature was abetted—it can only be—by a hangover from early anarchy: translating ideas as fast as I could into deeds overrode every thought of punishment or danger; as I seem to have been unusually active and restless, the result was chaos.

If these meetings are carried off with enough studied nonchalance, a dark and baleful fame begins to surround the victim, and it makes him, in the end, an infliction past bearing.

He is a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness which makes one anxious about his influence on other boys.’

To change scenery; abandon London and England and set out across Europe like a tramp—or, as I characteristically phrased it to myself, like a pilgrim or a palmer, an errant scholar, a broken knight or the hero of The Cloister and the Hearth!

I wondered during the first few days whether to enlist a companion; but I knew that the enterprise had to be solitary and the break complete. I wanted to think, write, stay or move on at my own speed and unencumbered, to gaze at things with a changed eye and listen to new tongues that were untainted by a single familiar word.

‘Leave thy home, O youth, and seek out alien shores... Yield not to misfortune: the far-off Danube shall know thee, the cold North-wind and the untroubled kingdom of Canopus and the men who gaze on the new birth of Phoebus or upon his setting...’

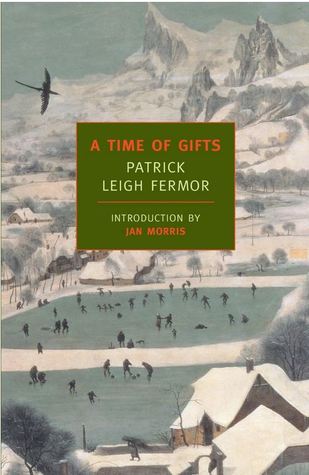

In Holland the landscape is the protagonist, and merely human events—even one so extraordinary as Icarus falling head first in the sea because the wax in his artificial wings has melted—are secondary details: next to Brueghel’s ploughed field and trees and sailing ship and ploughman, the falling aeronaut is insignificant. So compelling is the identity of picture and reality that all along my path numberless dawdling afternoons in museums were being summoned back to life and set in motion.

It was a time when friendships and families were breaking up all over Germany.)

Catullus—a dozen short poems and stretches of the Attis—because the young are prone (at least I was) to identify themselves with him when feeling angry, lonely, misunderstood, besotted, ill-starred or crossed in love.

life. A fair picture, in fact, of my intellectual state-of-play: backward-looking, haphazard, unscholarly and, especially in Greek, marked with the blemish of untimely breaking-off. (I’ve tried to catch up since with mixed results.)

The wax hardens and the stylus scrapes in vain.

To a strange eye, one is drunk or a lunatic.

Fierce winters give birth to their antidotes:

When I turned my back on these ranges, the pictures indoors still crowded my mind. They unloosed vague broodings on how large a part geography and hazard play in one’s knowledge and one’s ignorance of painting.

The idea that they are always welcome is a protective illusion of the young.

All dwellers in the Teutonic north, looking out at the winter sky, are subject to spasms of a nearly irresistable pull, when the entire Italian peninsula from Trieste to Agrigento begins to function like a lodestone.

I had heard someone say that Vienna combined the splendour of a capital with the familiarity of a village.

A hint of touchy Counter-Reformation aggression accompanies some ecclesiastical Baroque.

‘Östlich von Wien fängt der Orient an.’[2]

A different cast had streamed on stage and the whole plot had changed.

The settlements of the Czechs and the Slovaks were no more than early landmarks in this voluminous flux. On it went: over the fallen fences of the Roman Empire; past the flat territories of the Avars; across the great rivers and through the Balkan passes and into the dilapidated provinces of the Empire of the East: silently soaking in, spreading like liquid across blotting paper with the speed of a game of Grandmother’s Steps. Chroniclers only noticed them every century or so and at intervals of several hundred miles. They filled up Eastern Europe until their spread through the barbarous void

...more

Few readers can know as little about these new regions as I did. But, as they were to be the background for the next few hundred miles of travel, I felt more involved in them every day. All at once I was surrounded by fresh clues—the moulding on a window, the cut of a beard, overheard syllables, an unfamiliar shape of a horse or a hat, a shift of accent, the taste of a new drink, the occasional unfamiliar lettering—and the accumulating fragments were beginning to cohere like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Then, at the astonishing sound of Magyar—a dactylic canter where the ictus of every initial syllable set off a troop of identical vowels with their accents all swerving one way like wheat-ears in the wind—the scene changed.

Enmeshed in smoke and the fumes of plum-brandy with paprika-pods sizzling on the charcoal, they were hiccupping festive dactyls to each other and unsteadily clinking their tenth thimblefuls of palinka:

Liquor distilled from peach and plum, charcoal-smoke, paprika, garlic, poppy seed—these hints to the nostril and the tongue were joined by signals that addressed themselves to the ear, softly at first and soon more insistently: the flutter of light hammers over the wires of a zither, glissandos on violin strings that dropped and swooped in a mesh of unfamiliar patterns, and, once, the liquid notes of a harp. They were harbingers of a deviant and intoxicating new music that would only break loose in full strength on the Hungarian side of the Danube.

Here and there a pretty newcomer resembled a dropped plant about to be trodden flat.

But it grew noisier after dark when shadows brought confidence and the plum-brandy began to bite home.

It was aesthetically astonishing too, a Jacob’s ladder tilted between the rooftops and the sky, crowded with shuffling ghosts and with angels long fallen and moulting. I could never tire of it.

The invisible watershed shares its snowfalls with the Polish slopes and the tremendous Carpathian barrier, forested hiding-place of boars and wolves and bears, climbs and sweeps for hundreds of miles beyond the reach of even memory’s eye.

It was as if an entire civilization were sliding into calamity and taking the world with it.