Distance and transportation… part 2

This is a development on from my earlier blog on this topic which generated a number of interesting comments at different places. The issues which aroused comments were mainly to do with the numbers quoted:

Dawn achieved an acceleration of around 1/100,000 that of Earth’s gravity…I am assuming that advances in technology bring that up to 1/20 gravity, which leads to a top speed around 130,000 m/s.

First, the top speed I was thinking about relates to my Earth-asteroid belt journey, not any sort of absolute maximum. My main concern when I wrote it was that it was a tiny fraction of the speed of light. Even for an Earth-Pluto trip the turnover speed is only about 1% of light speed – which makes life and calculation a lot simpler. If you were able to carry on with the drive over a period of months or years – say in an attempt to travel to a nearby star – then you would have to take Einstein’s relativity into account.

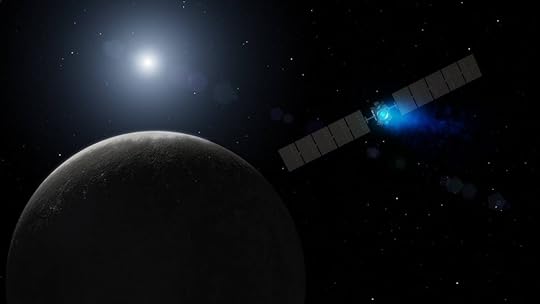

NASA/JPL image – artist’s impression of Dawn

NASA/JPL image – artist’s impression of DawnA brief digression on how rockets work. Basically you propel something in one direction in order to travel in the opposite one – the larger the objects you throw out, the faster you get to go, but on the other hand you run out of fuel quicker. Or, the faster you propel them in that direction, the faster you go, but that needs good engine design. In principle you can throw large objects very slowly, but it would be a frustrating business – much better to throw small objects very fast! The fastest ‘propellant’ would be a beam of light, and the most efficient engine would completely transform some piece of matter into that light energy. The Dawn probe used atoms of xenon as propellant, on the grounds that they are easy to ionise (and hence use as propellant) and are also unreactive while being stored prior to use. The exhaust velocity was in the region of 20,000-50,000 meters per second.

Now, so long as you have fuel, you can go on accelerating, and since your ship is continually getting lighter as you burn fuel, the acceleration tends to increase, unless you throttle back to achieve greater efficiency. The next question is – how long does your fuel last? There’s a trade-off here – if you had a more powerful engine then it would use fuel at a higher rate, but since you get to your destination quicker, you might still come out ahead. When Dawn left Earth orbit, about 1/3 of the mass was fuel (a little over 400kg), but then the engines have been used multiple times to achieve all kinds of exploratory moves.

A solution which is popular in science fiction is to gather your fuel as you go along, typically by sucking up interstellar hydrogen in an arrangement of electromagnetic fields called a Bussard collector – the theoretical science is real, though to date we have not actually built spaceships which use it. Star Trek’s Enterprise claims to be equipped with these, alongside the vastly more exotic warp drive to achieve faster than light travel.

If you had a total conversion engine firing, let’s say, a laser beam from the ship, your fuel cost is very minimal for journeys within the solar system – the Earth-asteroid trip costs you only a few grams of propellant, which presumably you would just carry in your pocket. In Far from the Spaceports I have deliberately not gone to that extreme. Nor, in fact, have I quantified the mass required for these journeys, but have made the assumption that it is a real though not dominant consideration. Mitnash has to purchase “reaction mass” at a spares yard after arrival at his destination St Mary’s, but the design of his ship, the Harbour Porpoise, is not overwhelmed by fuel tanks. Imagine something like a few tens of kilograms of fuel – say the equivalent of a few large suitcases.

Finally, none of these figures take into account getting away from the surface of a “proper” planet like Earth. That is a separate problem, involving high impetus. An ion drive is fantastic at maintaining low impulse for long periods of time, but nearly useless at the high levels of thrust needed for lift-off from a planet. I have assumed that there are regular shuttles of some design which take travellers from Earth’s surface to Low Earth Orbit (broadly speaking at a similar altitude to today’s International Space Station), and that the ion-drive ships take over from orbit on the long haul trips.