Despite His Conviction Being Quashed Three Times, Guantánamo Prisoner Ali Hamza Al-Bahlul Remains in Solitary Confinement

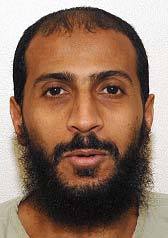

For some prisoners held in the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo Bay, it seems there really is no way out. One example would seem to be Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, a 45-year old Yemeni prisoner and a propagandist for al-Qaeda, who made a promotional video glorifying the attack on the USS Cole in October 2000, in which 17 US soldiers died, and who received a life sentence for providing material support for terrorism, conspiring with al-Qaeda and soliciting murder after a one-sided military commission trial in the dying days of the Bush administration.

For some prisoners held in the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo Bay, it seems there really is no way out. One example would seem to be Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, a 45-year old Yemeni prisoner and a propagandist for al-Qaeda, who made a promotional video glorifying the attack on the USS Cole in October 2000, in which 17 US soldiers died, and who received a life sentence for providing material support for terrorism, conspiring with al-Qaeda and soliciting murder after a one-sided military commission trial in the dying days of the Bush administration.

Al-Bahlul has been held in solitary confinement ever since — on what is known as “Convicts’ Corridor,” according to Carol Rosenberg of the Miami Herald, even though, since January 2013, he has had every part of his conviction overturned in the US courts — most recently in a ruling by the appeals court in Washington D.C. (the D.C. Circuit Court) on June 12.

In January 2013, a three-judge panel in the D.C. Circuit Court overturned the material support and solicitation convictions, on the basis that the charges of which he was convicted were not recognized as war crimes at the time he was accused of committing them; or, to put it another way, that they had been invented as war crimes by Congress. That ruling was confirmed by a full panel of judges in July 2014, and the judges last month overturned the conspiracy conviction — on the basis that conspiracy is not a crime under the international law of war.

I didn’t have time to write about that ruling at the time, but it was a huge blow — another huge blow — to the tattered credibility of the military commissions. Only eight convictions have been secured since the commissions were first revived by the Bush administration in November 2001. The commissions were ruled illegal by the Supreme Court in June 2006, but were revived again by Congress later that year, and revived again under President Obama in 2009, although they should never have been revived at all, as they are, simply, not fit for purpose.

Rosenberg first wrote about “Convicts’ Corridor” — a block in Camp 5 — in February 2011, when four men convicted in the military commissions were held: the former child prisoner Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen, and Ibrahim al-Qosi and Noor Uthman Muhammed, from Sudan. Al-Qosi was repatriated in July 2012, Khadr in September 2012, and Noor Uthman Muhammed in December 2013, following the terms of their plea deals.

Back in February 2011, military defense lawyers said that “Convicts’ Corridor” was “especially austere” and that their clients were “doing hard time reminiscent of Guantánamo’s early years when interrogators isolated captives of interest.” The military disputed that. Carol Rosenberg noted that, although each man spent “12 or more hours a day locked behind a steel door inside a 12-by-8-foot cell equipped with a bed, a sink and a toilet,” they got “up to eight hours off the cellblock in an open-air recreation yard,” and “[i]f recreation time coincide[d] with one of Islam’s five times daily calls to prayer, the convicts [could] pray together. If it coincide[d] with meal time, they [could] eat together.”

For the last 20 months, however, al-Bahlul has been completely alone.

Army Col. David Heath, the commander of the Joint Detention Group, who is in charge of the guard force, told Carol Rosenberg last week that, “absent a specific order to change the status of Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, [he] remains a convict,” unlike the 115 other prisoners who are described as “detainees,” including, as Rosenberg also noted, “the six former CIA captives who await death-penalty trials by military commission and two who have provisionally pleaded guilty but not been sentenced.”

As Rosenberg also noted, Col. Heath said that al-Bahlul, who is “considered a compliant convict,” remains on “Convicts’ Corridor” because he “has received no specific order from his military chain-of-command to move him. If so ordered, Heath said, he would then consult with the captive to see whether he was interested in joining other medium-security, cooperative captives in a communal cellblock.”

As Col. Heath put it, “If he reverted to detainee status, given his compliancy level, he would be entitled to communal.” It is not known, however, if al-Bahlul would wish to move, even if he is given the opportunity to do so, although, if he did, he would be the first convicted prisoner to do so. However, Rosenberg noted that, according to military commanders at the prison, “[a]n undisclosed number of other compliant captives voluntarily live in solitary cells … rather than join the majority living in groups of a dozen or more who pray, eat, watch TV and play some sports together with the exception of two hours of daily lockdown in individual cell situations.”

While we wait to see if al-Bahlul’s status changes, or if the Obama administration will yet again appeal, either to a full panel in the D.C. Circuit Court, or to the Supreme Court, I’m cross-posting below the editorial published in the New York Times following al-Bahlul’s third and hugely significant court victory — and below that are my thoughts on the military’s rather ludicrous claims that seven men — in addition to the seven “high-value detainees” currently involved in extensive, and seemingly endless pre-trial hearings — might still be prosecuted, when a sober analysis of the situation would, instead, indicate that no one else will be charged.

A Rebuke to Military Tribunals

New York Times editorial, June 18, 2015

In 2008, Ali al-Bahlul, a propagandist for Al-Qaeda who has been held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, since early 2002, was convicted by the military tribunal there and sentenced to life in prison. But officials had no evidence that Mr. Bahlul was involved in any war crimes, so they charged him instead with domestic crimes, including conspiracy and material support of terrorism.

Last Friday, a panel of the federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., reversed Mr. Bahlul’s conspiracy conviction because, it said, the Constitution only permits military tribunals to handle prosecutions of war crimes, like intentionally targeting civilians. (The court previously threw out the other charges on narrower grounds.)

The 2-1 decision, by Circuit Judge Judith Rogers, was a major rebuke to the government’s persistent and misguided reliance on the tribunals, which operate in a legal no man’s land, unconstrained by standard constitutional guarantees and rules of evidence that define the functioning of the nation’s civilian courts.

Of course, that was the whole point of the tribunals, as their architects in the Bush administration saw it: they held out the promise of relatively quick trials and easy convictions, beyond the reach of the Constitution and the scrutiny of the American public. But it didn’t work out that way. As with Mr. Bahlul, most of the prisoners at Guantánamo could not be linked to specific attacks. So in 2006 and 2009, Congress gave the tribunals the authority to try certain domestic crimes, even though legal scholars had repeatedly warned that this was an unconstitutional transfer of jurisdiction away from the federal courts.

The appellate panel’s majority agreed. If the government were to prevail, Judge David Tatel wrote in concurrence, “Congress would have virtually unlimited authority to bring any crime within the jurisdiction of military commissions — even theft or murder — so long as it related in some way to an ongoing war or the armed forces.”

America’s civilian courts are not just the constitutionally proper place to try federal crimes, Judge Tatel added, they are very good at it. “Federal courts hand down thousands of conspiracy convictions each year, on everything from gun-running to financial fraud to, most important here, terrorism.”

In fact, federal prosecutors have won almost 200 “jihadist-related” terrorism and national-security cases since Sept. 11, Judge Tatel pointed out. Most of these involved conspiracy charges — including the case against the potential 20th hijacker, Zacarias Moussaoui. Meanwhile, the commissions have resulted in only eight convictions, despite charges against about 200 detainees — and all but one of those convictions were based on charges that are not war crimes. The commissions’ former chief prosecutor called this record a “litany of failure.”

In other words, while the commissions continue to stumble, the federal courts are more than capable of handling the prosecution of people like Mr. Bahlul without hiding from the mandates of the Constitution. And the tribunals may still try detainees for war crimes, as they are continuing to do with the five men charged with orchestrating the 9/11 attacks.

The Obama administration, which has also fought to allow the tribunals to try conspiracy cases, could still ask the full appeals court to reconsider the panel’s ruling, or it could appeal directly to the Supreme Court. Either route would be a mistake.

The Guantánamo Bay detention center still holds 116 men 13 years after it was opened, nearly half of whom have long been cleared for release, and each of whom costs Americans about $2.7 million a year to imprison. It is a legal and constitutional black hole that dishonors principles of justice and due process. Mr. Obama promised to close it the moment he became president, but Congress has stubbornly refused to let that happen. Now, after last week’s ruling, almost no one remains who can be prosecuted by the military tribunals at Guantánamo.

*****

Despite the likelihood that al-Bahlul would win his appeal against his conspiracy charge, making it probable that the only trials that can continue are those of the alleged 9/11 co-conspirators (Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four others) and of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, the Miami Herald reported that, in March, Pentagon officials were still hoping to prosecute another seven of the men still held, even though, of the eight convictions to date, four have now been overturned — in the cases of Salim Hamdan, Noor Uthman Muhammed and David Hicks, as well as al-Bahlul. In addition, Omar Khadr is challenging his 2010 conviction, and of the other three convictions, two of the men in question — Majid Khan and Ahmed al-Darbi — are still at Guantánamo, and their sentences are dependent on their cooperation.

The Miami Herald article noted that “[t]he long-range vision for trials through 2019 was included in a 362-page release of internal discussions surrounding a since abandoned plan to base judges permanently” at Guantánamo — a plan that went down with the judges like a lead balloon. Prosecutors had tried to keep the documents secret, but a judge, Air Force Col. Vance Spath, “reviewed them and ruled they could be released.”

The names of six prisoners featured on a chart dated October 31, 2014 include the “high value detainees” Mohd Farik bin Amin and Bashir bin Lap (aka Mohammed bin Lep), Malaysians who were captured in Bangkok in 2003 and held in CIA “black sites.” They are alleged accomplices of Hambali (Riduan Isomuddin — or Isamuddin), who was added as a seventh name in November after Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, the chief war crimes prosecutor, conceded in a memo that he had been “inadvertently omitted” from the list.

However, revelations in the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA torture program, released in December, may well have derailed the plans. As the Miami Herald noted, “Agents stripped, shackled and deprived Hambali of sleep to soften him up for his 2003 interrogations, according to a public portion of the report, and an interrogator subsequently told him he would never have his day in court because ‘we can never let the world know what I have done to you.’”

It was also noted that, after Hambali’s capture in August 2003, President George W. Bush “called him ‘one of the world’s most lethal terrorists’ and said that he was ‘suspected of planning major terrorist operations’ — notably an al-Qaida affiliate’s 2002 bombing of a nightclub in the Indonesian resort of Bali that killed 202 people.” However, the Senate report quoted a CIA cable from November 2003, which stated, “Hambali’s role in al-Qaida terrorist activity was more limited than the CIA had assessed prior to his capture,” adding that al-Qaida members “thought him incapable of ‘leading an effort to plan, orchestrate and execute complicated operations on his own.'”

The others intended for prosecution are the Yemenis Abdu Ali Sharqawi (aka Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Haj), an alleged former recruiter of bodyguards for Osama bin Laden, known as “Riyadh the Facilitator,” and Sanad al-Kazimi (aka al-Kazmi), allegedly a bodyguard for bin Laden. However, both men’s torture in secret CIA prisons, before their arrival at Guantánamo in September 2004, was public knowledge even before the executive summary of the torture report was issued – see here and here, for example — which would complicate plans for prosecutions, even if the government’s allegations are trustworthy, something that is by no means certain.

Also listed is Abdul Zahir, an Afghan first charged with attacking civilians in the first incarnation of the military commissions under President Bush, whose case I wrote about here. The charges against him were dropped, and never reinstated when the commissions were revived in 2006 and again in 2009.

The last of the seven, ludicrously, is the Egyptian Tariq al-Sawah, who was approved for release by a Periodic Review Board in February, “suggesting a trial has since been ruled out,” as the Miami Herald politely described it. Al-Sawah had been put forward for a trial in 2008, but the charges had been dropped, and it was always a ridiculous proposal, as he has apparently been one of the most productive informants in the prison, and it is, frankly, insane to suggest that informants should be prosecuted for their efforts.

In Guantánamo, however, as anyone playing close attention realizes, the insane can — and often is — re-imagined as sensible policy. In the real world, however, all the latest news has done is to make it clearer than ever that the military commissions at Guantánamo should be scrapped, and those who can be tried should be moved to the US mainland to face federal court trials — while everyone else is released.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Andy Worthington's Blog

- Andy Worthington's profile

- 3 followers