Bad Advice Wednesday: Why Not Say What Happened?

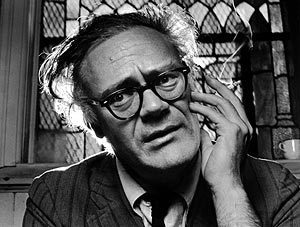

Robert Lowell

One of the most-asked questions at writer’s conferences and here on the Bill and Dave’s Bad Advice hotline is about the dangers of hurting or offending or simply alerting people who will appear in a memoir or even, disguised, in fiction. Here’s a particularly cogent version of the question, which we’ll keep anonymous by request: “I’m planning a memoir of my growing up partly in Nigeria, partly in London, mostly in the Chicago area. I’m terribly worried about offending my mother, who is sensitive about some of the material in the book (my father ended up in prison, and rightly so). Also, I’m worried about my children reading this material, as they are not fully aware of their grandfather’s story, nor mine (I have a checkered past, to say it mildly). How do you handle sensitive material when it will be out and about for all the world to read?”

First of all, this sounds like a great story. And my initial response is sympathetic. But then I want to ask, Why are you worrying about this now? You need to write the book first before you can know what to worry about. Write it unbridled. If the story is haunting you, get it on paper. Get it right both factually and emotionally, both technically and dramatically. This will take a couple of years. Later, you can always make adjustments to protect the innocent or not-so-innocent.

Better yet, like most memoirists, you may find that having found the truth means no adjustments are necessary. Like many, you may find that publication is elusive in any case. Like some, however, the big day is going to come. Most publishers give a legal reading to such manuscripts, try to determine if anyone’s privacy is being violated, or if any libel is being committed, and etc., and request changes, often artful obfuscations.

Before that, most editors will ask if you’ve made any disguises, changed names, fudged locations (above, for example, I said Nigeria and Chicago instead of your real country of origin and city of residence, since you asked to be anonymous). And a good editor will help you avoid trouble with some tried-and-true methods of disguise, up to and including composite characters. Then again, as the star of a memoir, you can’t very well change your name and identifying characteristics. And changing Mother’s name to Mommy won’t help much either. One enterprising friend attributed all her very most controversial behavior (she’d been a sex worker) to her sister, Ann. But she didn’t have a sister. My sense is it kind of worked–anyway, the memoir went forward, its point not being the sex trade but the effects of sexual abuse in her family.

Another possible strategy is to eschew publication till your mother is gone and your kids grown up, or maybe never. We don’t always write for publication.

Then again, we always do. So while you’re looking out for the feelings of others, remember that it’s your story, too, a story you have every right to tell.

Sometimes I’ve heard other writers suggest that you try your manuscript on all the people you’ve adopted as characters. But that seems a sure way to water things down, especially if controversy is involved. (If there’s no controversy, where’s the story?) Even with this strategy, I’d vote for writing the book first. And maybe act as a reporter rather than as a writer with a manuscript to vet. That is, interview your people, get their side of the story, and make sure you include their side in your book, if only to smash it. The interview will also have the effect of letting your people know what you’re up to. If there are going to be lawsuits, maybe better to get them sorted out in advance.

But really, most people are pleased to find themselves written about, especially if what they read sounds right, especially if what they read is well made. I’ve found that people love the stuff I was most afraid to say about them, and take offense at the most minor, surprising things: “Love how you handled my indecent-exposure trial, but I’d never wear a pink shirt to court!” And sometimes, as with your mother, a good book on a shared life can open up new channels of communication.

As for your kids, maybe it’s like the movies. There’s G, PG, PG-13, NC-17, and X. Eventually, they’ll reach the appropriate age for whatever your story holds. If you’ve been checkered enough, you might even find you’ve impressed them. Moreso, you might find they already know a great deal you never knew they knew. Because the things you do leave a trace. Just something about you, something that especially your own kids can detect. And isn’t it better to be who you are for those you love? I mean when they’re ready for it? So they know (as our “culture” likes to forget), that very good people can come out of very bad experiences?

Here’s a poem by Robert Lowell that speaks to the issue, and gives this week’s Bad Advice its title:

Epilogue

Those blessèd structures, plot and rhyme–

why are they no help to me now

I want to make

something imagined, not recalled?

I hear the noise of my own voice:

The painter’s vision is not a lens,

it trembles to caress the light.

But sometimes everything I write

with the threadbare art of my eye

seems a snapshot,

lurid, rapid, garish, grouped,

heightened from life,

yet paralyzed by fact.

All’s misalliance.

Yet why not say what happened?

Pray for the grace of accuracy

Vermeer gave to the sun’s illumination

stealing like the tide across a map

to his girl solid with yearning.

We are poor passing facts,

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.