Connascence of Value

Connascence is a way of describing the coupling between different parts of a codebase. And because it classifies the relative strength of that coupling, connascence can be used as a tool to help prioritise what should be refactored first.

For example, let’s tackle @pragdave‘s classic Back to the Checkout kata in Java. My first test checks that we can scan a single item and calculate the total correctly:

public class CheckoutTests {

@Test

public void basicPrices() {

Checkout checkout = new Checkout();

checkout.scan("A");

assertEquals(50, checkout.currentBalance());

}

}

Now I make it pass in the simplest way I can think of:

class Checkout {

public int currentBalance() {

return 50;

}

public Checkout scan(String item) { }

}

Clearly these two classes are now coupled (if they weren’t, the test wouldn’t pass). But is that coupling good or bad?

I can see three four kinds of connascence between the test and the production code:

Connascence of Name, because the test knows the names of the methods to call on the checkout object. This is level 1 (of 9) on the connascence scale — the weakest and least damaging form of coupling.

Connascence of Type, because the test knows which class to instantiate. This is level 2 on the scale, and is thus also relatively benign.

Connascence of Meaning, because both classes know that we are representing monetary values using ints. (I missed this first time around — d’oh!)

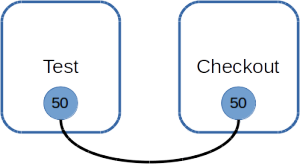

Connascence of Value, because both the test and the Checkout know the price of item “A”:

The Connascence of Value here means that the tests will break if I change the price of item “A”; I definitely wouldn’t want to release this into production.

Connascence of Value is level 8 on the scale of 9 types of connascence. The scale defines seven weaker forms of coupling, and only one more serious kind. I can use that model to help me prioritise the Refactor step in my TDD cycle: Connascence of Value is a serious problem, and should be fixed before I do anything else. The only question is: how?

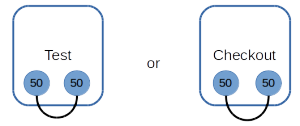

The first thing I note is that connascence is weaker with proximity, which means that either of the following options would be preferable:

Thus, if I can move knowledge of the price of “A” so that only one of my classes has it, then the effects of the coupling are greatly diminished.

I can get some help from SOLID here, because the Dependency Inversion Principle also tells me that this code has a problem. The DIP says that we should depend on abstractions, not on details. And yet here I have a test that only works due to its knowledge of one of the details inside the production code.

The DIP (and @jbrains) also tells me what to do next: I should move the detail up towards the tests. That means I need to change the Checkout so that the test injects the value 50 via a parameter. I could pass it in via the scan method:

public class CheckoutTests {

@Test

public void basicPrices() {

Checkout checkout = new Checkout();

checkout.scan("A", 50);

assertEquals(50, checkout.currentBalance());

}

}

Alternatively I could inject it via the Checkout’s constructor:

public class CheckoutTests {

@Test

public void basicPrices() {

Checkout checkout = new Checkout(50);

checkout.scan("A");

assertEquals(50, checkout.currentBalance());

}

}

Either way, I have now removed the Connascence of Value between the Checkout and the test: I can change the price of item “A” by changing only one method.

The worst of the coupling is now gone, but I can do better. There is still Connascence of Value, albeit very localized, within that test method. Is it worth fixing?

I like my tests to be expressive and easy to read. I wouldn’t want to extract the value 50 to a constant, for example, because I would then have to scan up and down through the test class to discover exactly what the test was doing. But equally, that magic value 50 makes me a little nervous. Does it have business significance? Not in this case, and a new team member might not pick that up.

In cases such as this I like my tests to use random values, to help ensure that the code under test hasn’t made any unfortunate assumptions. So I replace that 50 with a call to a random price generator:

public class CheckoutTests {

@Test

public void basicPrices() {

Checkout checkout = new Checkout();

checkout.scan("A", randomPrice());

assertEquals(randomPrice(), checkout.balance());

}

}

But now the test is broken again, and that Connascence of Value is the guilty party, telling us that the two values need to be the same. I fix it by replacing the Connascence of Value by Connascence of Name:

public class CheckoutTests {

@Test

public void basicPrices() {

Checkout checkout = new Checkout();

int priceOfA = randomPrice();

checkout.scan("A", priceOfA);

assertEquals(priceOfA, checkout.balance());

}

}

To summarise, I find connascence useful in guiding my refactoring efforts during the TDD cycle. In this case, I weakened the coupling between the code and test by pushing details up the call stack; then I removed the Connascence of Value altogether by replacing it with Connascence of Name.

Kevin Rutherford's Blog

- Kevin Rutherford's profile

- 20 followers