Fear of Falling

You can laugh. I’ll laugh, too, someday I’m sure, but not quite yet.

Yesterday, I set out from Glenwood Springs Colorado, elevation 5,763 ft., intending to drive to Scottsdale, Arizona, elevation 1,277 ft. A long day on the road, probably 12 hours with necessary stops, but certainly doable. And, hey, it’s all downhill, right?

So around noon, I approached the little community of Ouray, a quaint old mining town that stretches along US 550 in the San Juan Mountains. Yes, I noticed the pale green shading on the map that indicates a mountain drive, but I’d just crossed the Rockies on I-70 the previous day, and I’d ventured as far into the clouds as Aspen, 7,890 ft. to visit galleries and a bookstore. For a Texas flatlander who grew up in Houston, elevation 125 ft. at the loftiest point – notice that’s only 3 digits – this was high adventure.

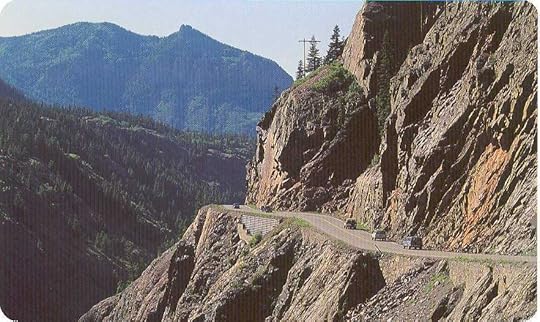

Indeed, some of the two-lane highway leading into Ouray became breathtaking enough to make me feel adventurous. I even stopped at one turnout and took photographs, the landscape was that gorgeous.

Here’s the bit from Wikipedia that I didn’t think to read until later: Ouray … marks the beginning of the Million Dollar Highway. This stretch of highway connects Ouray to its neighboring cities of Silverton and Durango. The Million Dollar Highway is frequently regarded as one of the most beautiful roads in Colorado, but is also considered one of the most dangerous due to its sharp turns, steep ledges, and lack of guard rails.

My little Avalon’s steering wheel screamed “ouch” and I became intimately acquainted with low gear as I listened to the soothing sounds of Mr. Aker Bilk (“Stranger on the Shore,” etc.) and kept telling myself, “it’s okay, Chris, it’s okay. Millions of people before you have driven this passage without falling off.”

About that time I notice a blue triangular road sign: PLEASE DRIVE SAFELY, IN MEMORY OF….

Fodder

What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, right? And every experience is like fodder for a writer’s imagination. “I can do this,” I kept muttering. After all, that 18-wheeler ahead of me made the turn okay, even though the road slants precariously in the wrong direction as it curves into a sharp U. And the motorcycle riders are doing fine. Relax, and this too shall pass.

To be fair, I had to also remind myself that I’d driven the mountain pass to Taos, New Mexico one year in a blizzard. Never forgot it, and never planned to repeat it. That was the year I stopped vacationing during winter months.

About five miles the other side of Ouray, I began to wonder if I’d taken the wrong road. Having seen no US 550 marker for some time, I reasoned that this dangerous passage couldn’t be the highway to Durango. I must have gotten off on one of the back roads. Again, I pulled over at a turnout. This one was large enough to straddle the highway, and a number of vehicles were parked there – the adventurous soles had obviously abandoned them for a hike into the upper stratosphere.

Taking my map as I exited the car, I breathed cool, clear mountain air and tried to think soothing thoughts. A couple of motorcyclists stopped on the other side of the road. When they took off their helmets and I saw big smiles on their faces, I figured they had to know the territory, so I crossed the road and asked if I’d gotten lost.

“No, you’re on the right road,” they assured me. Apparently, they had just come down from a trail suitable only for off-road vehicles, one that got too hairy even for them to make it all the way up.

“So, is the highway like this all the way to Durango?” I indicated the 82-mile stretch marked with light green shading on my map.

“Well … it might get a little flatter … no, I guess it’s all pretty much like what you’ve been driving. Is Durango where you’re headed?”

“Actually, I’d hoped to reach Scottsdale.”

“Hmmmm ….” Shaking their heads. “Probably not tonight. You have a couple more hours of this and you can’t go more than 35 or 40. When you get behind trucks or camper trailers, they’ll slow you down.”

The legal speed limit over much of the stretch I’d driven so far was 25 mph. Those are the white signs. Yellow signs suggested taking certain curves at 15 mph, others at 10.

“I’m not too worried about other drivers slowing me down,” I said. “I’ll always be in the slowest car on the road.”

Within the next mile, I felt my grip and my jaw tighten with anxiety and realized I was holding my breath. Then I recalled a bit of writing wisdom: When describing those sticky emotions that most writers find bothersome, concentrate on the physical changes happening internally.

Psychologists have postulated for decades that humans are born with only two fears – fear of loud noises and fear of falling – both of which are part of our survival instincts. All other negative emotions are learned.

If that was true, then it was perfectly okay, and in fact normal, for me to be shaking in my Sketchers when I slowed to 10 mph on a curve that seemed barely an arm’s length from toppling me over thousands of vertical feet of rock and vegetation. Hundreds of other motorists were probably feeling the same dread at that very moment. For some reason, my shoulders relaxed a bit with that thought. My fear of falling off the mountain was both reasonable and commonly acceptable.

It’s also interesting to notice that feelings tend to dissipate in the presence of rational thought. As we examine our emotions, the strength goes out of them – for an instant or so, at least. So when writing emotions, the best thing we can do as writers is to place ourselves in the emotional state we’re trying to describe. I recall a Charlie Brown comic strip in which Charlie is standing limp-shouldered, vacantly staring down at the floor. When Lucy asks, “What’s wrong?”, Charlie says, “I’m depressed. This is how you do it.”

Try it. Slump your shoulders, look down, and let all your facial muscles fall. Now mentally try to feel excitement or enthusiasm. It’s pretty near impossible.

In contrast, smile broadly, with teeth showing, jump up, thrust your fists into the air and shout, “Yes!” At the same time, try to be sad or angry.

Put yourself physically into the emotion you want to describe, then notice the physical changes that occur, and quickly, before those feelings escape, jot down what was happening internally and any further manifestations that occur spontaneously in your outward appearance.

Now, save those notes for the next time you want to write that emotion.

Eventually, I Arrived at Silverton

This little town was like finding the eye of a hurricane, a respite of flat ground large enough to sport a gas station, convenience store and a sigh that declared ALL SERVICES AVAILABLE YEAR ROUND. Though I had slightly more than half a tank of gas, I filled it, noticing that the tall coffee I’d purchased before leaving Glenwood Springs was gone and the caffeine had given me the shakes. At least, I wanted to attribute the shakes to caffeine, though I’d eaten a pretty good breakfast and I also had finished off a 20-oz bottle of water, knowing that it’s important to stay hydrated in higher altitudes.

Inside the convenience store, I discovered frozen milkshakes. You open one then place it in a machine that whips it into a drinkable consistency – and it was an unexpectedly tasty milkshake, I should add, with enough milk fat and protein to help me overcome caffeine jitters, I reasoned.

The motorcyclists I’d met earlier arrived shortly after I did, and we chatted for a bit. My jitters calmed somewhat, but not entirely.

I drank more water while I asked the store personnel about local accommodations. Even though it was still only 3:00, Durango was still 50 miles away (at an average of 25 mph), and I simply didn’t feel I should drive any farther.

Solace awaited me in the form of a delightful B&B just a few blocks away. I checked in, carried only one small bag up a single flight of stairs, and began digging through my purse for the rescue inhaler I keep there. Like anyone with asthma, I always have one nearby, though I hadn’t had occasion to use it in months.

It helped, but I still felt sick and wobbly. It occurred to me that I might have a touch of altitude sickness. After resting a bit, I carried my laptop upstairs and Googled the elevation here: 9,305 ft. Red Mountain Pass, the 12-mile stretch of the Million Dollar Highway I’d driven from Ouray, reaches 11,118 ft., surrounded by 13,000-ft peaks. No wonder this Texas flatlander got the jitters.

Tomorrow, I’ll tackle the remainder of my drive to a bookstore in Durango, then continue on to the Scottsdale area, where I’ll visit four more independent bookstores plus a few art galleries, then on to Santa Fe, New Mexico for a repeat. All good. These several weeks have been quite a treat, filled with family and fun, and lots of new friends – not to mention the wealth of writer’s fodder I’ve accumulated.

But I can predict that once I arrive home at Hilltop Lakes, Texas, elevation 486 ft., I’m going to keep my tires firmly planted for a while.