DESCRIBING STUFF

Your characters are obviously more important than their settings, but there is a critical and creative synergy between character and setting--a synergy that takes place in the reader’s brain.

The late, great John D. MacDonald codified it this way: "When the environment is less real, the people you put into that environment become less believable, and less interesting."

He illustrated his point with two descriptive passages. Here is the first:

“The air conditioning unit in the motel room window was old and somewhat noisy.” MacDonald called this an image cut out of gray paper. It triggers no vivid visual image.

“The air conditioning unit in the motel room window was old and somewhat noisy.” MacDonald called this an image cut out of gray paper. It triggers no vivid visual image.By contrast, see what happens in the imagination while reading this passage:

"The air conditioning unit in the motel room had a final fraction of its name left, an 'aire' in silver plastic, so loose that when it resonated to the coughing thud of the compressor, it would blur. A rusty water stain on the green wall under the unit was shaped like the bottom half of Texas. From the stained grid, the air conditioner exhaled its stale and icy breath into the room, redolent of chemicals and of someone burning garbage far, far away."

From these close-up clues, MacDonald said, you the reader can construct the rest of the room--bed, carpeting, shower, with vivid pictures from your own experience. The trick is how much to describe--the telling detail--and what to leave out. Too much detail and you turn the reader into a spectator, no longer part of the creative partnership whereby the reader fills in the rest of the scene out of experience and imagination.

“No two readers will see exactly the same motel room,” he added. But “the pictures you have composed in your head are more vivid than the ones I would try to describe.”

Note that MacDonald did not label the air conditioner as old or noisy or battered or cheap. Those are all subjective words, evaluations that the reader should make. “Do not say a man looks seedy. That is a judgment, not a description. All over the world, millions of men look seedy, each one in his own fashion. Describe a cracked lens on his glasses, a bow fixed with stained tape, an odor of old laundry.”

Note also that MacDonald is using sensory cues in his quick sketch of the air conditioner. You not only see the bottom half of Texas, you smell the burning garbage, you hear the coughing thud.

There are many masters of detailed description. One that comes to mind is the late Joseph Hansen, author of the David Brandstetter mysteries. Here is an example, picked almost at random from his 1973 novel, Death Claims :

“…The front wall was glass for the view of the bay. It was salt-misted, but it let him see the room. Neglected. Dust blurred the spooled maple of furniture that was old but used to better care. The faded chintz slipcovers needed straightening. Threads of cobwebs spanned lapshades. And on a coffee table stood plates soiled from a meal eaten days ago—canned roast-beef hash, ketchup—dregs of coffee in a cup, half a glass of dead, varnish liquid…”

It’s clearly of a piece with MacDonald’s example. But Hansen, a poet as well as novelist, seems to describe everything, every setting, every character, with such laser-like attention to detail, while MacDonald picks his spots. For me as a reader, exhaustive detail is exhausting.

There are celebrated passages, of course, where an author intends to glut the reader with overflowing detail. A famous example occurs in Gustave Flaubert’s descriptions of Madame Bovary’s wedding, in which every costume and every menu course is lavished with loving prose:

There are celebrated passages, of course, where an author intends to glut the reader with overflowing detail. A famous example occurs in Gustave Flaubert’s descriptions of Madame Bovary’s wedding, in which every costume and every menu course is lavished with loving prose:“Upon [the table] there stood four sirloins, six dishes of hashed chicken, stewed veal, three legs of mutton and, in the centre, a comely roast sucking-pig flanked with four hogs-puddings garnished with sorrel. At each corner was a decanter filled with spirits. Sweet cider in bottles was fizzling out round the corks, and every glass had already been charged with wine to the brim. Yellow custard in great dishes, which would undulate at the slightest jog of the table, displayed on its smooth surface the initials of the wedded pair in arabesques of candied peel…”

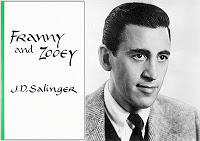

MacDonald cites another exception to the less-is-more dictum: “In one of the Franny and Zooey stories, [J.D.] Salinger describes the contents of a medicine cabinet shelf by shelf in such infinite detail that finally a curious monumentality is achieved…”

*

Published on July 25, 2013 13:54

No comments have been added yet.