Bradley Manning Trial: No Secrets in WikiLeaks’ Guantánamo Files, Just Evidence of Colossal Incompetence

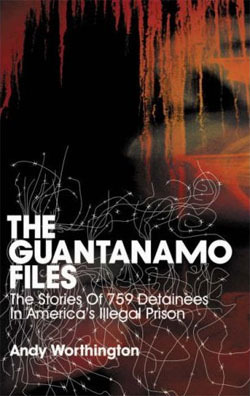

Last week, just before the defense rested its case in the trial of Pfc. Bradley Manning, I was delighted that my book The Guantánamo Files was cited as a significant source of reliable information about the prisoners in Guantánamo — more reliable, in fact, than the information contained in the previously classified military files (the Detainee Assessment Briefs) leaked by Manning and released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, on which I worked as a media partner.

Last week, just before the defense rested its case in the trial of Pfc. Bradley Manning, I was delighted that my book The Guantánamo Files was cited as a significant source of reliable information about the prisoners in Guantánamo — more reliable, in fact, than the information contained in the previously classified military files (the Detainee Assessment Briefs) leaked by Manning and released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, on which I worked as a media partner.

The trial began at the start of June, but on February 28, Manning accepted responsibility for the largest leak of classified documents in US history — including the “Collateral Murder” video, featuring US personnel indiscriminately killing civilians and two Reuters reporters in Iraq, 500,000 army reports (the Afghan War logs and the Iraq War logs), 250,000 US diplomatic cables, and the Guantánamo files.

When Manning accepted responsibility for the leaks, the Guardian described it as follows: “In a highly unusual move for a defendant in such a serious criminal prosecution, Manning pleaded guilty to 10 lesser charges out of his own volition – not as part of a plea bargain with the prosecution.” The Guardian added that the charges to which Manning pleaded guilty “carry a two-year maximum sentence each, committing Manning to a possible upper limit of 20 years in military prison,” but pointed out that he “pleaded not guilty to 12 counts which relate to the major offences of which he is accused by the US government. Specifically, he denied he had been involved in ‘aiding the enemy’ — the idea that he knowingly gave help to al-Qaida and caused secret intelligence to be published on the internet, aware that by doing so it would become available to the enemy.”

This was central to the case put forward by the prosecution, which spent two weeks, and called 80 witnesses, in an attempt to portray Manning as, essentially, a traitor — an argument that, I hope, they failed to make adequately, as it is ridiculous.

If the prosecution succeeds, Manning faces a maximum sentence of 149 years in military custody, but as he said in February, his intention all along was to “spark a debate” about the behavior of the US government and the military — something that many millions of people (myself included) have regarded as hugely important, revealing the horrors of war, what Manning regarded as the dangerous opacity of US diplomacy, and, of course, the revelations about Guantánamo contained in the Detainee Assessment Briefs.

As Manning said in February, “We were obsessed with capturing and killing human targets on lists and ignoring goals and missions. I believed if the public, particularly the American public, could see this it could spark a debate on the military and our foreign policy in general [that] might cause society to reconsider the need to engage in counter-terrorism while ignoring the human situation of the people we engaged with every day.”

Speaking of the 250,000 US diplomatic cables, Manning said that he was convinced they they would embarrass but not damage the US, and the same, I believe, is true of the Guantánamo files.

As I stated just before his trial began, at the start of June:

Bradley’s key statement on the Guantánamo files is when he says, “the more I became educated on the topic, it seemed that we found ourselves holding an increasing number of individuals indefinitely that we believed or knew to be innocent, low-level foot soldiers that did not have useful intelligence and would’ve been released if they were held in theater.”

I added that this was “absolutely the case,” but I also made a point of noting that, although, as Manning noted, they were only “intended to provide general background information on each detainee — not a detailed assessment,” what was crucially important about the release of the files was that “they provide the names of the men making the statements about their fellow prisoners, which were not available previously, providing a compelling insight into the full range of unreliable witnesses, to the extent that pages and pages of information that, on the surface, might look acceptable, are revealed under scrutiny to be completely worthless.”

Last Wednesday, testifying for the defense, Col. Morris Davis, the former chief prosecutor of the military commissions at Guantánamo, who resigned in 2007 in protest at the Bush administration’s plans to use information derived through the use of torture, and has since become a powerful opponent of the many injustices of the prison, specifically addressed Manning’s release of the Guantánamo files.

As the Guardian described it, Col. Davis “told the court that he had compared a sample of the detainee files leaked by Manning to WikiLeaks against public information that was freely available at the time of the disclosure,” and “said he found considerable overlap and repetition, and even passages in the official detainee assessments that were almost verbatim copies of publicly-available material.”

“A lot of the information was repetitive of comparable open-source information that was available in print,” Davis said. “You could read the open-source information and sit down and write a substantial version of what was in the DAB.”

The Guardian added that the purpose of Col. Davis’s testimony was to “rebut the allegation” that Manning had communicated classified information “with reason to believe such information could be used to the injury of the US or to the advantage of any foreign nation.”

Manning has specifically been charged in relation to five of the files released in 2011 (which, it appears, include those relating to several released British prisoners, and possibly Shaker Aamer, who is still held) and Col. Davis explained that he had compared the five leaked files with “information released by the government itself, including Pentagon publications from 2006-07 on the combatant status of the detainees” — the 8,000 pages that formed the basis of my work, and are extremely important, although, as I note above, they generally lack the specific names available in the DABs.

Davis also said that he had “checked against information provided in newspaper articles, a docu-drama called The Road to Guantánamo and a book, The Guantánamo Files, that was published three years before the WikiLeaks disclosures. He said he had concluded that ‘if you watch the movie, read the book and the articles, you would know more about them than if you read the detainee assessment briefs.’”

Davis also said that he had “checked against information provided in newspaper articles, a docu-drama called The Road to Guantánamo and a book, The Guantánamo Files, that was published three years before the WikiLeaks disclosures. He said he had concluded that ‘if you watch the movie, read the book and the articles, you would know more about them than if you read the detainee assessment briefs.’”

Manning’s defence lawyer, David Coombs, asked Col. Davis if the information in the DABs “could have been useful to enemy groups” — a question relating to the charge of “aiding the enemy” that Manning faces, to which Davis replied that “his review found that the Guantánamo files did not contain intelligence on sources or military methods that would have had potential value to the enemy.”

As he said, “As far as providing sensitive information, it doesn’t do that — it is just background information. We described them as ‘baseball cards’ – it was just who the individual was, a ‘Who’s John Smith?’-type description of the individual.”

I was delighted to be cited by Col. Davis, and I believe that the main thrust of his argument is indeed accurate, but what it misses is the extent to which the information in the files ought to be a profound embarrassment to the US, as the parade of unreliable witnesses in the pages of the files reveals the prison as nothing less than a factory of torture and coercion devoted to extracting false statements from prisoners to be used to make a case against their fellow prisoners, or to make a case against themselves.

I hope, in the near future, to resume my detailed analysis of the files, as the painful truth is that many of the 166 men still held — including the majority of the 80 men recommended for indefinite detention without charge or trial or for prosecution by the inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, appointed by President Obama, which reviewed all the men’s cases in 2009 — are held on the basis of the profoundly unreliable information exposed in the Guantánamo files. In contrast to the prosecution’s claims, the only damage this information can do the US involves embarrassment.

As I mentioned in the heading to this article, the Guantánamo files that Bradley Manning helped to bring to the world’s attention reveal, primarily, that the mill of torture and coercion established by George W. Bush is not just a place where the crimes of torture and indefinite detention have been committed by the Bush administration — and now by Obama — but is also a place where its intelligence gathering procedures can — and should — be generally described as an almost unparalleled example of colossal incompetence.

POSTSCRIPT: On July 10, the final day of testimony for the defense, the final witness was the Harvard law professor Yochai Benkler, who, as the Guardian described it, “delivered blistering testimony in which he portrayed WikiLeaks as a legitimate web-based journalistic organisation. He also warned the judge presiding in the case, Colonel Denise Lind, that if the ‘aiding the enemy’ charge was interpreted broadly to suggest that handing information to a website that could be read by anyone with access to the internet was the equivalent of handing to the enemy, then that serious criminal accusation could be levelled against all media outlets that published on the web.”

Benkler, the co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, appeared as an expert on the future of journalism in the digital age. He “dismissed any connection between WikiLeaks and terrorist organisations and damned as ‘a relatively mediocre effort’ a counter-intelligence report titled ‘Wikileaks.org — An Online Reference to Foreign Intelligence Services, Insurgents, or Terrorist Groups?’”

The Guardian added, “Although the US government has leant heavily on that report in making its case against the army private, telling the court that there had been forensic evidence that Manning had accessed the document on several occasions. But Benkler said that the report did the opposite of what the government intended — it showed WikiLeaks in the light of a journalistic organization: ‘In many places it describes WikiLeaks staff as writers or editors,’ he said.”

Benkler also told the court that, according to his reading of the Pentagon report, “there is little doubt that [WikiLeaks] is a journalistic, hard-hitting journalistic investigative organisation.”

*****

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Andy Worthington's Blog

- Andy Worthington's profile

- 3 followers