A Drawing a Day: #4

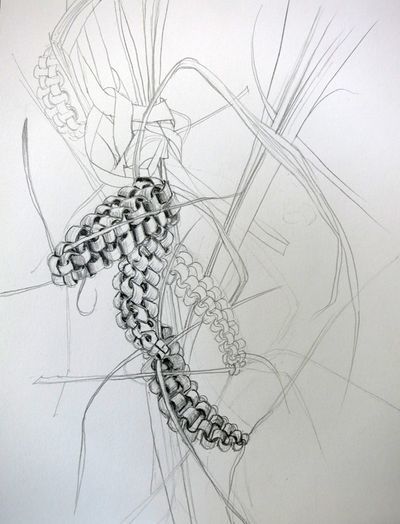

Study of Quebecois braided palms. Pencil on paper, 8 1/2" x 11". Click image for larger view.

It's pretty crazy to sit and draw something like this, but I've been wanting to use these palms as part of a painting or a large drawing, and knew I needed to make a detailed drawing of them first to get their structure in my mind. I've been putting it off, for obvious reasons, but once I got going I enjoyed doing it.

We've had these now-dried braided palms in a brass vase since Palm Sunday a year ago, and I just love them - the original green has faded to a light straw color, and the forms are very pleasing to me. I had never seen this technique before moving to Quebec. I learned how to make them from a friend who has been braiding them since childhood. It's the same basic braiding technique as the plastic four-strand lanyards some of you may have made in summer camp as kids. But it's a different story to draw them! First I sketched in the proportions and placements for the study, and then started with the most detailed cluster, at the top, drawing a light outline of the whole shape and then dividing it into four sections to contain the two top row of curved segments and the two rows on the side. Then I counted the actual number of loops, and drew the basic structure with a very hard pencil, then went back and added the shadow detail with a darker, softer pencil, and finally used the harder one to add the midtones and a more definite, firmer edge. By the time I'd drawn this first cluster, I had "gotten" the structure in my head, and could then draw the others a lot faster without having to constantly refer to the object itself. At the end I added the background detail of the taller palm fronds.

It's that way with a lot of things that occur in nature or have some sort of repetitive pattern - you have to study how the pattern works and then you can reproduce it, but if you don't figure it out you can't see why your drawing isn't working, and then you're just drawing by rote, which is totally exhausting. A pinecone would be a another good example, or the whorl of seeds in the center of a sunflower. It's like solving a little visual enigma.

If I use these palms again I may want to draw them very freely - and that would be impossible -- for me, anyway -- without going through this exercise.

I remember once having a professional job of making business cards and a brochure for a woman who did creative knitting. She wanted a background image of a piece of knitting - mostly straight stockinette stitch - but with some increases and decreases that created curved areas on the flat surface. At the time we had an employee who was quite talented in design. I asked her to draw the image, lifesize, using the knitted sample as her guide. She produced several samples, but they were all wrong -- as it turned out, she couldn't "see" the basic structure of the knit stitch. Even when I explained it and showed her, in a simple sketch, where the thread went and what went over and what wentunder, she couldn't reproduce it. I think that was because she really couldn't "see" it. This was a sobering realization for me, and it made me question some assumptions I'd always made about visual perception and intellectual understanding - perceptions based on how my own mind works, obviously. It was also a lesson for me as an employer -- I had asked her to do something, under a deadline, that she couldn't do easily at all, and she had ended up feeling frustrated and like she had failed, even though I tried really hard to backtrack and not leave her with that impression. I've always felt bad about that, and I know what it feels like: the physical sciences and certain aspects of technology have at times reduced me to tears, and my inability to grasp basic concepts embarrasses me the most when when well-meaning friends who do "get it" are trying to explain the subjects to me. I hate feeling stupid or inept; is it any wonder we avoid the areas where we don't have natural aptitude, and gravitate toward those where we do? Different people's minds are simply different.

I still wonder, though, if it's possible to teach someone to see this way, and how much of the disconnect between hand and eye that makes many of us feel that we "can't draw" is the result of bad experiences of not "doing it right," how much is temperament, and how much is a difference in our brains. No matter how expressive we may want to be, or are encouraged to be, for most people drawing still starts with attempts to reproduce what they see. A good teacher can do a lot, I think, to help overcome the fears and frustrations, and to help the pupil learn to see visual relationships and structures. I've always felt that most people can draw far better than they think, but it does take practice and patience -- and kindness.