Flesh and Bones

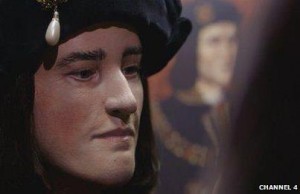

The discovery of the skeleton of Richard III, and the subsequent media frenzy, has reawakened intense debate over the nature of the man. Now that we have a better idea of his physical features – from the curvature of his spine to his facial reconstruction – the spotlight will again fall on whether he was a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ man.

The discovery of the skeleton of Richard III, and the subsequent media frenzy, has reawakened intense debate over the nature of the man. Now that we have a better idea of his physical features – from the curvature of his spine to his facial reconstruction – the spotlight will again fall on whether he was a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ man.

This has long been debated; in fact this has been the subject for conjecture for nearly five centuries, so much so that this king – who reigned for a little over two years – has captured worldwide attention and a loyal following. Over 3000 people are members of The Richard III Society, an organization dedicated to research into the life and times of the last Plantagenet king. Not whitewashing – as some detractors habitually insist – but a thorough investigation to restore balance to the debate.

Richard was undoubtedly the victim of the Tudor victory after the Battle of Bosworth on the 22nd August, 1485 in more ways than the loss of his life. That he should fall foul of the Tudors’ need to establish themselves on the throne to which they had poor claim, was inevitable. That this legacy should have such an abiding fascination, remarkable.

Partially, I suspect, many people like to dwell on the macabre. Then there is the all-too human tendency to pigeonhole individuals using neat, easy descriptions: Philip the Good, Charles the Bold, Sven Forkbeard. And a generation ago, children were still being taught that Richard was responsible for the deaths of a multitude of late medieval notables including Edward, son of Henry VI, Richard’s brother, George (remember the butt of malmsey?), and even his own wife. Richard was the king history loved to hate; a larger-than-life figure, whose supposed actions required nothing more than a cursory glance and a grimace. He was made easy to despise. It takes effort to look below the surface; what is more, it requires patience, perseverance, an open mind, and more original and untainted sources than we have knowledge of.

Boar badge insignia of Richard III

And keeping an open mind is nigh on impossible if you have been brought up in a culture where there are frequent negative references to this man. Many, of course, derive from that brilliantly contrived Shakespearian character. Indeed, no documentary on Richard is complete without film clips of Olivier’s charismatic rendition. Should we resent Shakespeare and his ilk for painting a memorable – if inaccurate – picture? Should we decry those historians and novelists who revert to the standard descriptors any more we should the ardent loyalists who do little to advance their cause by using emotive language? Not at all. For the truth is that without these polarized opinions, Richard would still be buried under a council car park – forgotten, unloved – fallen into obscurity as his brother Edward IV has done: a footnote in history before the onset of self-serving Tudor mythology. Interest in Richard III lives because both sides of the argument refuse to let their version of the king die.

The Richard III Society has its work cut out in establishing a balanced evaluation of Richard’s character and reign, but it is a battle worth fighting to establish a closer representation of the truth than has formally been presented. The point where science and obsession came together to reveal the whereabouts of this man was a historic moment. Whatever the outcome of the debate, future research will surely be stimulated by the extraordinary discovery that gave Richard back to the world, and reveal more about the life of this remarkable man.

[image error]