By the Book

I woke up tired this morning.

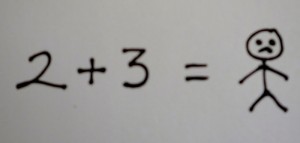

I am not a number

Yesterday, we attended a Parents’ Consultation with Child 2. We left it feeling frustrated and filled with a deep gloom. This was not because Child 2 had – in any way – been found wanting; in fact her teachers praised her attitude and behaviour. No, it wasn’t her that filled us with despondency, but the system that consistently fails children like her.

Child 2 is dyslexic. Not very, mind you – she can decode most words, her spelling is pretty good, and she is organised enough to get through each day. She does pretty well with her coursework and always hands homework in on time. Anything she might lack in terms of being an academic high-flyer, she more than makes up for in sheer determination and the sunniest disposition you could hope for in an individual. Except when it comes to exams.

She had returned from her trial exams (which we used to call ‘mocks’) before Christmas with mixed feelings.

“How did they go?” I asked her when she climbed into the car after the first day of exams.

“It was OK,” she said, “but I didn’t finish the paper.”

“Why?” I asked, wondering, as many parents must do, whether I had failed to support my offspring sufficiently.

“I ran out of time.”

My heart sank. This was a familiar cri de coeur.

“It took me too long to read the questions and understand what I had to do. And although I knew the answers, I couldn’t find them and get them in order quickly enough. I can’t think because everything is in my head all at once and I can’t select what I need. I can’t organise the information into sentences. It is like having everything and nothing all at one time. I can see billions of words, but I can’t pin them down. ”

“Never mind,” I smiled more encouragingly than I felt; “you tried your best. Let’s see how the rest of your exams go and then see what we can do.”

The rest followed a predictably erratic pattern: some she managed to finish, the rest she failed to complete.

So, yesterday evening, we sat in front of the specialist teacher.

“I know what you are going to say,” she said before we said anything, “but your daughter is already getting 15% extra time and the use of a laptop.”

“Yes, but she is still not able to finish her exams. What she is able to complete she does really well on, so it is not a question of knowledge, but a matter of time. She simply can’t retrieve and record the information quickly enough in exam conditions.”

A piece of paper is thrust under my nose showing the results of screening tests.

“As I’m sure you know because of your own experience at a specialist school,” she said, “the examination boards will only allow 25% extra time if one or more scores are at 84 or below. Your daughter’s scores are all above.”

My husband shifted in his chair, but remained grimly silent.

“I understand the guidelines of the examinations boards,” I replied evenly, “but a case can be made in special circumstances in which a pattern of need can be established, and we can clearly show that in exams, our daughter is not able to finish the papers. As a result, her results are down by between one and two predicted grades.”

The smile on the woman’s face became fixed. “She can’t have any more time; it wouldn’t be fair on the other candidates. The exam boards are clear.”

I did a double-take.

“How is it fair on our daughter if she is penalised for getting scores above 84 yet she can’t get the grades of which she is capable because she can’t finish the exam for lack of time?”

By this time, the woman’s face had become stony. “She needs to learn exam techniques.”

I sighed. “Granted exam techniques will help, but that will not stop the confusion of information in her brain that she has to fight every time she wants to write a sentence.”

“The training course I went on made it very clear,” she said, pushing the list of numbers closer across the table towards me. “I don’t want to be accused of malpractice.”

There was nowhere we could take this conversation. It was as if we came from opposing views and it reminded me sharply of one of the reasons why I became a dyslexia specialist in the first place. Child 2 aside, how many other children, students, and adults are caught in this trap: functioning at an above average level, and yet not able to achieve their full potential because the test results just do not reflect the reality of their difficulty?

Potential: there’s a word that is bandied about by many schools; yet how can a person’s full potential be realised when they are referred to in terms of test results on a piece of paper?

“Average is good enough,” this same specialist once told me when discussing Child 1, who has similar difficulties. “Why should your daughter be given an advantage over students who are average?”

I frowned, wondering which of us had missed the point. “Because she is struggling with a specific difficulty that is stopping her from achieving her best. It’s like telling someone with a mobility issue to run a race with able-bodied athletes and then taking away his crutches. If all she can achieve is an average set of results because that is her potential, that’s fine. But she is capable of more, which she clearly demonstrates when she has the time to finish the paper.”

As we left the Parents’ Consultation later that evening, demoralised by the lack of flexibility in the exam system that might prevent someone doing their best, it occurred to us that not once, in the entire conversation, had the specialist referred to our daughter as an individual. Our child had been reduced to a set of numbers.

If this is a familiar scenario and you have come up against the system at school, work or another situation, I’d like to hear your views. Is this a common problem, or is it just me?