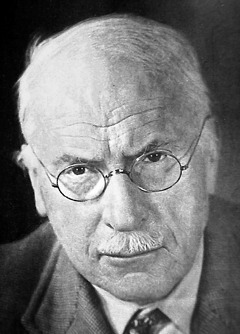

What Carl Jung Knew About Your Writing

The Eleventh Edition of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines the word archetype as the original pattern or model of which all things of the same type are representations or copies; also: a perfect example. An inherited idea or mode of thought in the psychology of Carl G. Jung that is derived from the experience of the race and is presence in the unconscious of the individual. Strangely, the word doesn’t appear in Webster’s Third New International Dictionary even though that tome was written in 1961 (the same year Carl Jung died), and Carl Jung had come to define the term in the early 30s.

The Eleventh Edition of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines the word archetype as the original pattern or model of which all things of the same type are representations or copies; also: a perfect example. An inherited idea or mode of thought in the psychology of Carl G. Jung that is derived from the experience of the race and is presence in the unconscious of the individual. Strangely, the word doesn’t appear in Webster’s Third New International Dictionary even though that tome was written in 1961 (the same year Carl Jung died), and Carl Jung had come to define the term in the early 30s.Although Carl Jung was the first to sort of accurately pinpoint them and hang a label on then, archetypes have been around as long as Plato who thought everything in the universe was a facsimile to a perfect form that existed somewhere. That perfect form would be what Jung would call the archetype. It was the ideal. The real life interpretations were simply shadows, trying to live up to the perfection of the ideal.

Where Jung made his discoveries regarding archetypes were the way they kept recurring in mythology, folklore, and dreams. Archetypes are not an invention of mankind. They are something that is built into the human psyche at birth. We expect to find them in our lives. So much so, we dream in archetypes. We think in archetypes. And, of course, we write in archetypes. We do it without even thinking, so, like most things we do without even thinking, there’s probably value to thinking about a little and learning what sort of value can be generated from learning how to use archetypes wisely.

Archetypes appear in your stories are character types. We know them well. For the sake of discussion, I’m just calling them archetypes as a sort of “catch all,” but most people refer to them as Jungian Archetypes, especially when speaking of them in this manner. Some archetypes you know so well they appear in every story you write, such as the archetype of the Hero and the Shadow. One is the protagonist on his quest toward his goal to save the day and capture the golden fleece and the other is the antagonist, dead set to put a stop to the Hero’s progress. Other archetypes is the Mentor–the wise old man who teaches the Hero how to fight and persuades him to venture forth into the unknown, or the Great Mother–the wholesome figure who takes in the Hero and nurtures him at his time of need, dressing his wounds and healing him, or the Damsel in Distress–the fair princess trapped at the top of the castle’s high tower waiting to be rescued by the dashing young protagonist after his final climactic battle against the Shadow antagonist.

So, you may very well ask, what’s the difference between archetypes and stereotypes? It’s a fair question, because the answer is a daunting one. It’s a fine line. Archetypes run the risk of becoming stereotypes when they are overused or used in clichéd ways. You do not want your Damsel in Distress to be the quintessential Damsel in Distress or your Great Mother to be the epitome of all Great Mothers. You want to use aspects of the archetype and rely on their power in your story the way you rely on spices to make a great pasta sauce. Archetypes have great power and readers expect to encounter them, but turn them on their heads; use them in ways that surprise readers; and you’ll find yourself writing fantastic stories that are truly unforgettable.

Think about the way Diablo Cody handled the father and stepmother in the movie Juno. At every turn, they went against the way you expected them to react to things and it worked fabulously. Instead of being the wicked step mother, she turned out to be the cool step mother who was on Juno’s side. Instead of freaking out and screaming at his daughter when he found she got herself pregnant while still I high school, Juno’s father took it calmly. The archetypes of the Father and the Step Mother were still present, they were just used differently. And they were made more powerful for it because it made the story modern and new.

Think about Mentors for a minute. Sure you can have an old wizard like Gandalf, or a wise old muppet like Yoda or Master Po from the 70s television show Kung Fu all handing out sage advice to young learners on the path to becoming warriors and that will work. It’s a tried and true method that has shown to be effective in story telling for probably thousands of years. But you can also make your Mentors bossy parents or over-protective grandparents or that psychic from the hotline on TV. . .

Types of Archetypes

There are many Jungian archetypes and you will do well to fill your writer’s toolbox with at least a dozen or so good ones. They give you lots to draw on while writing, especially when you get stuck somewhere.

Here’s just a small list of some common ones. You can research them on the Internet and find out much more about them and their qualities and what is expected out of them and how they act. You can also find a lot more archetypes once you start researching.

The Hero

The Shadow

The Self

The Mentor

The Anima

The Animus

The Child

The Martyr

The Great Mother

The Maiden

The Trickster

Many times archetypes will change their roles during the course of the story. In this way, archetypes are almost like masks. A character may wear the mask of the Mentor for a while and then wear the mask of the Shadow, such was the case of Hannibal Lechter in Silence of the Lambs.

If you haven’t already discovered the use of archetypes, I encourage you to dig deep into this untapped treasure trove of resources. You will find endless fascination with it; at least I do. There’s so much information available, you can literally keep researching for months on the topic and pretty soon you start becoming an expert in psychology, and even that is good for your writing.

Michael out.

Michael Hiebert's Blog

- Michael Hiebert's profile

- 99 followers