Three Act Plot Structure In Detail

A few weeks ago, I posted an entry about my writing style and how I usually approach my work using a three act structure. I mentioned that, until I had at least the four major cornerstones of that structure in place, I couldn’t really start writing. Those cornerstones are: the inciting event, the resolution, and the pivot points between Act I and Act II and Act II and Act III.

Today I’d like to go into a little more detail on my structured approach for anyone who might be interested. There are quite a few books out there that describe different methods of using this as a template, but most of them tend to overcomplicate things. I think I’ve managed to get the process down to as little parts are needed to successfully write a book without getting bogged down in process.

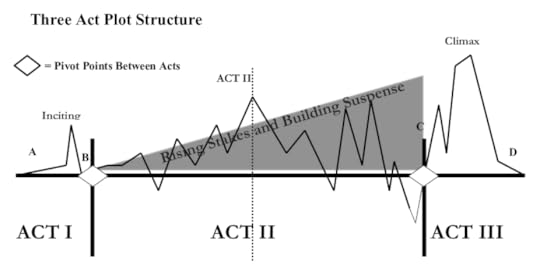

For the sake of those who may have missed it, here’s the graph of the three act plot structure I posted last time:

The first thing I want to do is clarify what I mean by “pivot points”. These are kind of confusing, because on the surface the pivot point between Act I and Act II (the place in your story where your protagonist crosses the threshold into the “new world” where there is no way of ever going back) seems to be the same as the inciting event.

It’s not.

Think of the inciting event as the initial big problem thrown at your story. The first part of your structure is your setup which shows your protagonist in his “normal world”. This is him as he is and has been every day of his life. In showing him here, you want to give a hint that things aren’t as great as they could be. The protagonist might be oblivious to this fact. Indeed, many are. That’s where we get the term “reluctant hero” from. Many protagonists think things are fine and dandy, even after their world starts erupting around them.

Once the normal world has been established (and this should be done as efficiently as possible because all time spent in this portion of your book is before the story starts, read: boring to the reader) you need to throw a wrench into the works. This is the inciting event that will kick off the story. It might be a meteor hurtling toward Earth or an iceberg getting in the way of the protagonist’s ocean liner or some storm troopers killing his uncle and aunt over a couple of droids or your hero’s favorite child getting a Buzz Lightyear for his birthday. Whatever it is, it’s a huge disruption in the hero’s life.

Now the protagonist is left with a choice. This is something important that is easily missed. The choice has to exist in the story. Does the protagonist act on the event, or does he simply ignore it? I call this stage the Debate stage. It can be anywhere from a paragraph to pages in length and it’s important because it’s during this stage that a reader first gets a glimpse of real characterization. We see a bit of what makes your character tick.

Now, we all know eventually the character’s going to act or we don’t have a story. But what’s it going to take? Some heroes are just ready to enter the fray. Some require a little guidance. Maybe a wizard visits his hobbit hole with some dwarfs and convinces him that heading out on a quest is actually a good idea after all.

The wizard in this case is acting as a Mentor which is probably the most common archetype that appears in stories. Knowing about archetypes can be very helpful while you are writing. I will talk about them in a later post. But just know that Mentors have a habit of popping up right near the end of acts, and they’re especially fond of the end of Act I (so is another special and very common archetype called a Threshold Guardian, but I won’t go into details about him here).

Whatever it is, the protagonist’s conscience, the persuasion of a Mentor, the advice of his friend he calls nightly on the Psychic Hotline, something finally ends the Debate phase of the story and the hero decides to take whatever action is needed to get him across the threshold from Act I into Act II. At this point in the story, he knows there is no turning back; he knows his life has now changed forever. It is because of this knowledge and whatever changes he just went through to arrive at the decision to act that we have an Act I/Act II pivot point.

This essentially describes what the pivot point is. It’s an emotional change in the character. It’s growth. Admittedly, it’s not very much growth compared to what we’ll see throughout the rest of the book (especially during the next act which makes up by far the largest portion of the story), but it’s growth just the same. Growth is what writing in the three act structure is all about. You want your protagonist to start one way and finish another. The bigger the difference between A and B, the more emotional potential your book will have. The technical term for this change is character arc. Your protagonist has to arc, and he has to start arcing right away. It’s good if other principal characters arc too, but it’s vital that your protagonist does.

Okay, now we’re past the pivot point and into Act II proper. This is a very common place to launch your subplots.

Before I go any further, I want to point something out. A lot of you might feel I’m trying to make you follow a formula with this “three act structure stuff”; like I’m trying to make all your writing come out one way and one way only. Let me assure you, there is nothing formulaic about it. You don’t have to follow all the rules. When I say things like, “This is a very common place for…” it doesn’t mean that’s the end all be all rule. Not every phase of the structure has to go where I lay it out here. You don’t even need to include every phase. You can juggle them around. You can add your own on top of them.

The way I like to put it is: we’re talking about form, not formula.

Think of the structure more like the structure of a house. Houses don’t follow a formula, but they are definitely built on structures. Yet, every house can be completely different from another. The structure is just there to make sure the house that is built has proper support. With the structure in place, the builder is free to make the more important design decisions that make the house unique without having to worry about the things that carpenters already solved for him hundreds of years ago.

This three act structure, by the way, goes back a little farther than hundreds of years. Aristotle was the first to describe it.

Okay, back to our subplots. Now you may have already started your subplots in Act I. You might not have any subplots. You might have five subplots and two are already going strong and one is going to start now and the other two won’t start until halfway through Act II. That’s all fine and dandy. I’m just saying it isn’t unusual for at least the major if not all the subplots to launch upon entering Act II.

And the major subplot, classically, involves a love interest.

Anyway, welcome to Act II. It’s daunting.

You’re sitting at your computer, looking down the barrel of a very long gun trying to even make out Act III and it’s nowhere in sight at this point.

Act II makes up a huge percentage of your novel. Probably ten percent of your book is taken up by the first act, maybe twenty or twenty-five by your third act and the rest all falls into that big wasteland known as Act II. Most novels sitting in drawers unfinished died somewhere in Act II.

If you read people like Christopher Vogler or Blake Snyder (especially Vogler) they try to give you little milestones throughout Act II–they have more fence posts lining their three act structures then me, making it look as though it makes the task easier, in the same way breaking up a big to do list into a bunch of little things makes it seem easier.

I don’t find that works for me. My act II is pretty barren as far as milestones go, I’m afraid. I just go with my gut. I will give you some hints, though, and a few places along the way where you have to stop and sight see.

First, always make sure your tension and your stakes are moving upwards. Keep the suspense up. There’s a great rule in writing: tell only what you need to, nothing more. Don’t tell anything until you need to. Hold everything back.

Put your protagonist in tight spots, get him out, and then put him in tighter spots. If you have a romance going on in either the foreground or the background, you already know the drill; we’ve seen it in movies enough that we can just feel how it should go: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy struggles to get girl back. That’s the hard and fast rule that always works. Just make yours work in new and exciting ways that nobody has ever thought of before.

Keep this up for the next hundred, hundred and fifty pages and you’ll be in full swing. If you start running out of ideas, have the men with the machine guns fall through the ceiling (don’t really do that–it’s been done to death now. Do something different, but just as surprisingly ridiculous. It usually works and takes your story in a direction you never expected it to go). Keep this up and you’ll soon hit the next major point in my structure which is:

The Act II midpoint.

This is the very middle of your novel, or pretty close to the middle anyway. This is an important place for you the writer and for us, the readers. It’s a great place for you because you get to relax a bit and do something different. If you watch a lot of movies or read a lot of books, you’ll start to notice that what every great story has near the middle is a pseudo-climax. You can build it just like you would the final climax to your book, only make sure your final climax is going to outshine the one in the middle.

I’ll give you an example. Think of the pod race in Star Wars Phantom Menace. That was almost too much of a false climax. For me, it overshadowed the actual climax, because I’d seen enough Jedi lightsaber battles to last me, well, a lifetime (or so I thought. Apparently, Mr. Lucas thought otherwise). The pod race happens in almost exactly the middle of the movie, right when Act II needed a severe rocket to the gut to get everyone’s attention perked up. And it worked.

Think this is only limited to action movies? Nope. All stories. How about the movie The Help? At the start, Skeeter’s interviewing Aibileen but is unable to get any of the other maids to talk because they’re too scared. Almost in the exact middle of that film is when Minny comes into Aibileen’s house during her interview and shouts at Skeeter for taking advantage of Aibileen. The tension builds, and you think she’s going to dissuade even Aibileen from talking as Skeeter tries explaining that she’s on their side. She’s hoping her work will bring change. The tension ramps up and Minny leaves in a huff closing the door behind her in a climactic slam until, a moment later, she opens it again and says, “Okay, I’ll do it.”

It’s a perfect midstory climax.

The Act II midpoint climax can resolve one of two ways: either as a peak (like both the examples I gave; Anikan wins the pod race, Skeeter gets to interview Minny), and it seems for the moment that things simply can’t get any better than they are, or as a down, and the world collapses around the hero and things seem like they can’t get any worse. If it’s a peak, it’s a false peak. If it’s a down, it’s a false down.

The conditions are false because we’ll learn that things can get more extreme than they are, and they soon do as we progress through the rest of Act II, continuing to maintain growing tension and raising stakes and trying to keep up any suspense we can.

Near the end of Act II we hit three major milestones. My terms for these may have been culled from other people, I’m not sure.

The first one I like to call Darkness Closes In. This happens just as things seem to be going all right. If Act II had been a little shaky, things finally seemed to be getting back on track and going okay for our protagonist. He and the reader can probably see progress being made toward whatever goal he has set out to attain. It’s at this point you want to toss a monkey wrench into his life. The bad guys regroup; the dark forces of evil swell; the girl he met at the swarma bar and fell in love with decides he smells to much like a garlic farmer and leaves him for his best friend Gordon who has two different colored eyes.

This naturally leads to the next phase, one that I definitely did lift. I stole it from Blake Snyder (writer of the excellent book “Save the Cat”). It’s called All is Lost.

This is where the hero suffers a false defeat. The hero thinks he’s come so far only to find he can’t possibly go any farther. It’s the end. You’ve seen this play out in countless movies and novels. It’s where Luke knows he can’t defeat Darth because he’s exhausted. Where the Joker in Dark Knight has the bombs on the boat and Batman can’t possibly save everyone with the way he’s devised his plan.

The hero suffers a breakdown. All hope is lost.

At this point, Joseph Campbell says the character must experience death. It doesn’t have to be a “real” death, although that works, too (In Star Wars, Obi-Wan gives up his life so that Luke and his buddies can make to the Falcon and get out before being shot). It can also be a metaphorical death. Either way, something inside the hero must die.

To quote Blake Snyder, he calls this the “whiff of death scene”.

The reason we need this is because the All is Lost point is our Christ on the Cross moment. It’s where the old world dies for good for our hero. His old way of thinking goes along with it, and everything he used to be is destroyed. This death clears the way for what he can now become.

My final phase of Act II is something I call The Dark Night Before Dawn. This may be only a few seconds for your hero or it may last five minutes. It’s the point right before he musters every last ounce of energy he has left and reaches deep down inside and pulls out that last, best idea that will save the day, which will happen in Act III. Right now, that moment is nowhere in sight. He’s out of ideas and out of strength.

This is a primordial story point. We’ve all been there: hopeless, clueless, drunk, stupid, sitting on the side of the road with a flat tire and no car jack (hopefully not all at once). Then, and only then, are we able to admit our humility and our humanity and give up our control and let fate hand the rest.

This plot point is all about humility. You want to show your hero has been beaten and knows it; show us that he’ll learn from this lesson.

You also want him to exhibit humility in a way that doesn’t knock your readers over the head with it. In other words, do it subtly.

We now hit our Act II/ActIII Pivot Point. By now, I don’t think I need to do much explaining on this one. You can see the emotional state represented by this stage of the structure. This is why it’s one of the four key states I need to have in my head before I start writing. The emotional state of my protagonist at this point in the book–right before I head into my climax–is a very important one, indeed.

Entering Act III is traditionally where all your subplots intertwine and tie up. Classically, it’s in the tying up of the romantic subplot that the idea for solving the ultimate problem of the protagonist comes from, but like everything about this structure, feel free to vary your mileage. Generally the hero gets the girl and the solution at the same time. However you do it, somehow the hero gets a potential solution to his predicament. Hopefully, it’s smart and fresh and something we didn’t see coming from a light year away.

Note that if you don’t tie up all your loose ends here, the best place to probably do it at this point is to wait until the denouement because you don’t really want anything to get between you and the resolution of your book now.

Next step is the climax. Things start wrapping up quickly now. Solutions are applied. If you’re writing a comedy, the main plot and subplots end in triumph for our hero. If you’re writing a tragedy, they end in death. If you’re being ironic, the hero doesn’t get what he wanted but discovers afterward his life is better for being unsuccessful.

The climax usually entails disposing of bad guys in ascending order. Henchman go first, then the boss. The main cause of the problem, whatever it is (a person or a thing) must be completely taken out. Movies supply endless examples. Look at Kill Bill, Lord of the Rings, The Avengers, etc.

But it’s not enough for a hero to just be triumphant. As I already said, the most important thing is character arc. Your protagonist has to change. He should have been gradually changing all through the tests and trials of Act II, but it’s not until the end of The Climax that the change has become final and complete.

And it must become final and complete in an emotionally charged and satisfying way. The hero must experience a resurrection of sorts, corresponding to the metaphorical death he went through at the All is Lost stage. Everything that has happened up to this point should have purposely led to this moment.

To quote Robert McKee, author of “Story”: “The story must build to a final action beyond which the audience cannot imagine another.”

That’s quite a task to undertake, don’t you think? Nobody said writing would be easy

After the climax, you’re pretty much done. In fact, you want to finish as soon as you can. The story’s done, so get out at your first chance. Everything written after The Climax is called The Denouement.

The Denouement is basically the bookend to The Setup at the beginning of the story. It’s a chance for readers to catch their breath after The Climax. It primarily exists for two reasons: first, it gives you a chance to wrap up any loose ends, and second (and more importantly) it gives your readers a chance to see the hero back in the real world having gone through his ordeal.

The world should not be the same as it was in The Setup. The protagonist has changed and with that change, his world has changed. The world is a better place for him having gone through all he did. This is a very important scene and without it your story would lose much power and meaning.

Well, that about wraps up this post. Sorry, I sort of went on a little longer than usual. Hopefully someone actually was interested in what I had to say.

Next time I’m going to talk about scene writing. And I plan to do another post on archetypes. Neither of those will be as long as this, I hope

Until then, Michael out.

Michael Hiebert's Blog

- Michael Hiebert's profile

- 99 followers