Contemporary Iterations and Adaptations of Frankenstein – What Would Mary Shelley Have Thought?

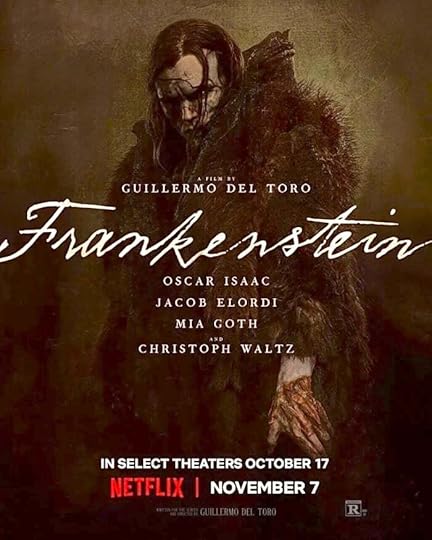

Despite having been written more than 200 years ago (published in 1818, to be exact), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has stood the test of time. There have been around a thousand adaptations of the story to date — with yet another, the 2025 film Frankenstein from the most recent to have joined their ranks.

In her book, with Frankenstein’s creature as her canvas, Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851) formed a distinct picture of society. Our “good” side manifests in the creature’s unexpected intelligence and elegant language, yet the “bad” layers of depression and violence begin to show as the story unfolds.

. . . . . . . . . .

Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025) is the latest adaption,

and it likely won’t be the last

. . . . . . . . .

Contrary to Shelley’s nuanced approach to human nature, popular adaptations such as The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Frankenstein Unbound (1990), and the most iconic of all, the 1931 horror classic starring Boris Karloff, have depicted the creature as a psychotic, murderous, and one-dimensional monster.

Have the lessons of the novel warped over time? Does popular culture see Frankenstein’s creature as anything beyond a villainous, monstrous caricature? And how have interpretations of the story changed since 1818 — especially as various sociopolitical issues, like feminism and environmental justice, have arisen throughout the 20th and 21st centuries?

. . . . . . . . .

Mary Shelley was barely out of her teens when she wrote Frankenstein

. . . . . . . . . .

Let’s explore a few of the countless adaptations of Frankenstein, how their values compare to the original, and most importantly (for our purposes anyway!), and speculated whether Mary Shelley would have approved based on her own politics and personal experience.

In the context of this article in mind, we can all go forth and experience del Toro’s iteration — and make our own judgments about Shelley’s possible opinions. We’ll start with another iconic film featuring Oscar Isaac as the creator…

. . . . . . . . . . .

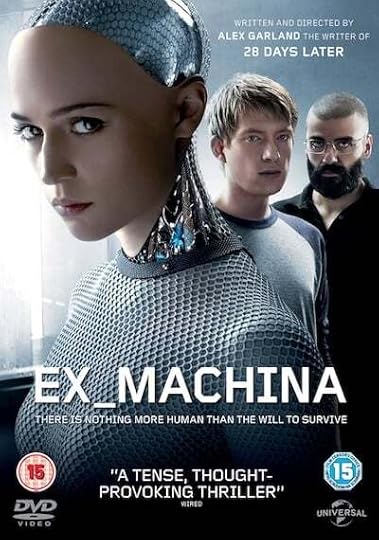

Ex Machina, dir. Alex Garland

Medium: Film

Year of adaptation: 2014

AI is rampant in our culture today, but the concept of it obviously originated much earlier. Indeed, Frankenstein’s monster is a patchwork of human parts, just as AI is a patchwork of human data. In Shelley’s story, the monster is eloquent and even charming — again, much like AI. But despite resembling a human being in many ways, the monster is not human, and is mistreated as a result.

This idea echoes through Ex Machina — a modern rendition of Frankenstein that reimagines the monster as a humanoid female robot named Ava. Though Ava is capable of intelligent thought, her creator Nathan disrespects her, viewing her as his own product rather than as an autonomous being. Nathan isolates Ava in his laboratory, controls her interactions, and it’s implied that he sexually abuses her as well — leaving us to wonder who the real “monster” is.

Both Ex Machina and Frankenstein shine a harsh light on the dangers of self-absorbed creators and unexpectedly powerful inventions. Nathan attempts to control Ava, convinced she is nothing more than a machine that wouldn’t exist without him. His moral failings and short-sightedness lead to his downfall.

Similarly, Victor Frankenstein obsesses over the idea of creating a new life, yet the reality of the creature’s autonomy plunges his life into chaos. Ultimately, instead of seeking redemption or trying to understand the creature, Victor obsesses over ending its life — a misguided venture that ends in his own death.

Mary Shelley’s exploration of the relationship between a creator and creation was likely influenced by her own upbringing. Her mother was an influential feminist, but died just days after giving birth to her.

Isolated throughout childhood, seventeen-year-old Mary sought solace in the arms of the poet Percy Shelley — a relationship her father disapproved of deeply. Mary’s father was more concerned with his status and reputation than preserving his relationship with his daughter — just as Victor Frankenstein and Nathan disregard their creations in favor of their own preferences and motives.

It would be fair to say that Mary Shelley likely would have appreciated Ex Machina as a (loose) adaptation. Furthermore, centuries before AI existed, Shelley was exploring the potential of artificial creation and themes of hubristic, selfish creators.

One clear undercurrent of Frankenstein is the importance of compassion, even for things we do not necessarily understand — an undercurrent that’s mirrored in Ex Machina. This may be one of the main reasons her work remains relevant (and frequently adapted) today.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . . .

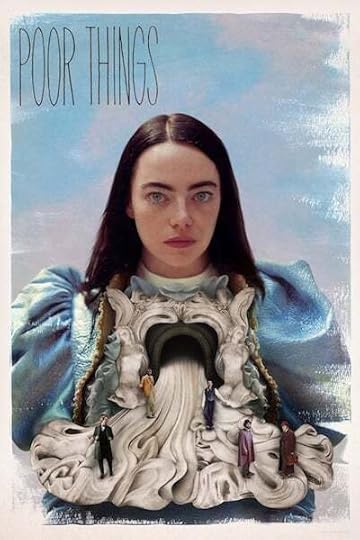

Poor Things, dir. Yorgos Lanthimos

Medium: Film

Year of adaptation: 2023

Poor Things took the world by storm when it was released in 2023. The film was hotly debated, with some viewing the story as ableist and gratuitous, while others claimed it was a feminist masterpiece. But what would Mary Shelley have thought?

Poor Things follows the life of Bella Baxter, a pregnant woman found dead by a troubled scientist named Godwin Baxter (a clever reference to Shelley’s maiden name). In an attempt to revive the woman, Godwin transplants the brain of her unborn child into her body. The twisted result is a seemingly grown woman with the mind of an innocent child — just as Frankenstein’s monster is created to be innocent and unknowing, at least at first.

Like the creature, Bella soon realizes that this world is not cut out for her. Many people try to take advantage of her, for her innocence and because she is a woman.

She’s constantly treated as possession rather than as a person, and specifically as a sexual object — especially disturbing given her childlike demeanor and speech. Still, the film does a good job (in this writer’s opinion) of keeping the tone amusingly satirical while also placing any ethical blame squarely on Bella’s would-be suitors.

Another loose Frankenstein interpretation — and one of the most iconic — strikes a similar tone. Richard O’Brien’s Rocky Horror Picture Show is a delightfully camp play in which a mad scientist creates the perfect lover for himself. And in both Poor Things and Rocky Horror, we see how satire can temper morbidity — something we don’t see in the original Frankenstein.

But while these more modern adaptations might have more fun, their moral impact is slightly lessened. Shelley’s novel raises philosophical questions in an eloquent, contemplative style (some might say “brooding”); these traits have helped make it into a literary classic.

Still, Poor Things — like Frankenstein, and also Ex Machina — raises important questions about control, freedom, and attraction. Just as Bella is confined and subjugated by those around her, so too is Frankenstein’s monster oppressed by his creator and by society. Poor Things arguably portrays Frankenstein’s power dynamics in an even blunter way, forcing the viewer to consider the dark implications of wielding power over the vulnerable.

Despite sharing similar values, though, it’s tough to say whether Mary Shelley would have enjoyed Poor Things. Shelley’s penchant for dark themes without comic relief perhaps means she wouldn’t have cared for a lighthearted adaptation like this one.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . .

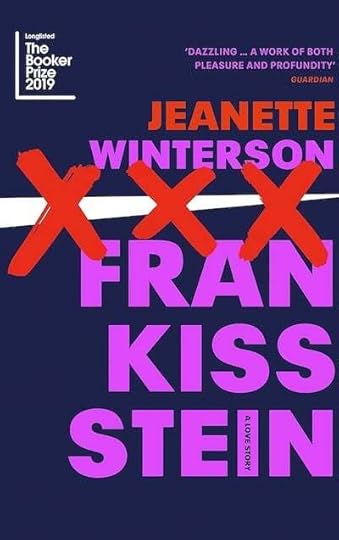

Medium: Book

Year of adaptation: 2019

In Frankissstein, one of her most recent novels, author Jeanette Winterson offers a sharp critique of society and human nature that echoes Mary Shelley’s social commentary. Both raise the question: can a corrupt society beget anything other than corruption? Furthermore, is a creation always morally compromised by its creator?

The novel’s protagonist Ry Shelley refers to themselves as a “hybrid”— neither male nor female. While Ry’s exploration of identity is rooted in human experience, we soon discover that a scientist called Victor Stein has different ideas for what human existence should be.

Combining identity with technological advancement, Stein envisions a future where humans can upload themselves to a vast AI mind. The story runs parallel to the exploits of Ron Lord, a businessman who favors AI for the creation of female sex robots.

Similar to the male characters in Poor Things, the characters of Victor Stein and Ron Lord clearly embody the dangers of toxic masculinity, albeit in contrasting ways. Like his progenitor Victor Frankenstein, Victor Stein aggressively pursues his technological goals with little concern for the consequences. Ron Lord, meanwhile, is selfish in a different way: less egotistical than simply misogynistic and entitled.

Of course, many would say that the original Frankenstein critiques toxic masculinity as well. Female voices in Shelley’s novel are largely silenced, overshadowed by the character arcs of Victor and his (male) creation. Female characters are sources of existential anguish (Victor’s mother), victims of the monster (Elizabeth Lavenza), or ideas which never come to fruition (the female mate for the creature).

On the surface, it might seem sexist not to have more female characters in Frankenstein — but as with the lascivious male characters in Poor Things, the absence of more substantial female representation here is commentary in and of itself.

Back to Winterson’s novel. In Frankissstein, present-day stories are skillfully interwoven with historical characters, including Mary Shelley herself. Shelley’s own life occurs in the book as it did 200 years ago, but with one twist — her creation, Victor Frankenstein, appears in her life as a real man.

These cleverly interwoven narratives suggest a multi-layered purpose to such a story: not only the author’s self-expression, but also what she imparts with her characters. Whether or not they are truly “alive”, our ideas have the capacity to take on lives of their own.

Winterson also contrasts Shelley’s ideas with modern existentialism, forcing the reader to consider the differences between morality in the 19th century vs. the modern day. And just like Victor Frankenstein and his monster, we start to realize there are more similarities between the two than it might originally seem.

This message — combined with their shared critique of toxic masculinity and the message of taking responsibility for our creations — makes Frankissstein an adaptation that Shelley would almost certainly have loved.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . .

Spare and Found Parts by Sarah Maria Griffin

Medium: Book

Year of adaptation: 2016

Sarah Maria Griffin’s dystopian novel Spare and Found Parts is set in a city, “The Pale,” which has been devastated by an epidemic. Many of its inhabitants have lost their original limbs and now have biomechanical ones. Our protagonist, Nell, has a literal mechanical heart — and aptly, she has always longed for connection and companionship. When she realizes she can build a friend for herself using other “spare and found parts,” she jumps at the chance.

But despite being a main character who creates life, Nell is the spiritual opposite of Victor Frankenstein. The Pale demands that each of its residents “contribute” something to the society once they come of age — and though Nell is a capable inventor, she’s extremely conscientious about her creations.

Unlike Victor, she cares that her new robot friend is looked after; also unlike Victor, Nell remains a clear force for good, even as dark forces threaten to encroach. Aside from her inherent morality, it’s possible that her own mechanical build might influence the empathetic approach to her creation. And there’s certainly a pure-of-heart message here about how our similarities are more important than our differences.

By transplanting the creator role onto a self-aware and socially conscious teenager, Griffin turns Shelley’s ideas into an uplifting story with a happy ending. Nell’s staunch integrity works as a rebuttal of sorts to Shelley’s warning on the corrupting nature of power — which maybe gives modern readers a bit of hope.

It’s unclear whether Shelley herself would have liked this, however. Her key themes in Frankenstein were intentionally macabre in order to reflect a dismal, decaying society and its corruptible citizens. That said, perhaps she would have appreciated a happier ending, given the torment that seemed to haunt her own life.

Mary Shelley’s estimated approval rating:

. . . . . . . . . .

Frankenstein has now outlived its creator by almost 200 years, and has grown from humble beginnings into its own formidable monster. Its influence continues to grip popular culture today, with more adaptations flowing out of pages and cinemas — and with the rise of AI, there’s no doubt that this cautionary tale still holds relevance. I bet Mary Shelley would have loved that.

Contributed by Juliet Allarton, a writer with Reedsy. In her spare time, Juliet enjoys reading fiction, working on her novel, and songwriting. She loves introspective stories that focus on people over plot, and her favorite book at the moment is Daughters of the Nile by Zahra Barri.

The post Contemporary Iterations and Adaptations of Frankenstein – What Would Mary Shelley Have Thought? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.