Rainforest | review by Rafe McGregor

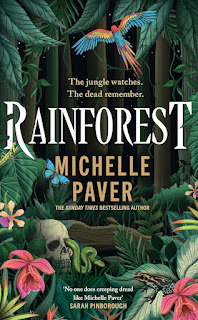

Rainforest by Michelle Paver

OrionBooks, hardback, £20.00, October 2025, ISBN 9781398723207

MichellePaver is an Oxford educated British author best known for her Chronicles ofAncient Darkness, a children’s fantasy series of nine books that began withWolf Brother in 2004 and concluded with Wolfbane in 2022. Thenovels are aimed at children from the ages of nine to thirteen, have beentranslated into thirty languages, and have sold over two and a half millioncopies. Paver has also published Daughters of Eden, an historicaltrilogy; Gods and Warriors, an historical series for children; and fivestandalone novels. All of her published work is historical in setting, albeitvarying dramatically, from six thousand to one hundred years in the past. Amongher standalone novels, three are horror stories: Dark Matter (2010),which is set in the Arctic in 1928; Thin Air (2016), set in theHimalayas in 1935; and Wakenhyrst (2019), set in the fens of EdwardianSuffolk. Dark Matter and Thin Air are two of the best horrornovels (or, more accurately, novellas) I have ever read. Until reading DarkMatter shortly after it was published, I’d considered James Buchan’s TheGate of Air: A Ghost Story (2008) my favourite contemporary horror story, but unlike the latter, Dark Matter and Thin Air have rewardedrepeated readings. Wakenhyrst is longer than its predecessors and of asimilar quality, although I found it harder going, which is because of myindifference to the haunted house trope rather than because of any flaws. (Imust confess that even Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House andRichard Matheson’s Hell House leave me cold…and I’m not referring to myspine.)

Rainforest is Paver’s twenty-third novel, sixthstandalone novel, and fourth horror novel. It also completes an informaltrilogy with Dark Matter and Thin Air, all of whom are about andnarrated by well educated, old fashioned British men who have difficultysocialising and lead conflicted inner lives. Writing with and in the voice ofanother gender is, I think, very difficult and Paver is one of the fewauthors to succeed completely. All three novellas (Rainforest is longer than the other two, but still a novella) read exactly as if they’d beenwritten by the protagonists Paver has presented with such and competence and convictionand all three are men we wouldn’t want to spend much time with, but whose livesare nonetheless captivating and compelling. The three novellas also demonstratean enviable expertise in representing the experiences of living and working ininhospitable environments – whether icy in temperature, high in altitude, or crushingin humidity – without resorting to lengthy exposition. Rainforest is, asthe title suggests, set in the Mexican rainforest, very likely the LacandonJungle, which was part of the Maya civilisation in the preclassic period, in1973. Dr Simon Corbett is a forty-two-year-old entomologist from Cambridge who specialises in the predation of mantids or Mantidae (praying mantises). Whenwe meet him, he is recovering from a mental health crisis connected to thedeath of a woman named Penelope and en route to an archaeological dig inthe jungle, where he hopes to both recover his equilibrium and resurrect astalled academic career.

Corbetthas been advised to keep a journal by his doctor and that journal is what constitutesthe majority of the novella. Penelope was, it appears, Corbett’s firstgirlfriend, which is the first suggestion of how much of a misfit he is (theirrelationship and her death both being recent). He also disapproves of the cultural,social, and political changes of the preceding decade, dislikes the IndigenousPeople of Mexico (a typically baseless and irrational racism), and is frightenedand disgusted by their ancient and contemporary rituals of self-mutilation. Paveris often compared to M.R. James and while there is definitely a ‘Jamesian’ atmosphereto and in her horror, there is also a ‘Lovecraftian’ scope and more accurate descriptionis that she combines the virtues of both masters of the weird tale with acontemporary sensibility and sensitivity in a way that may well be unique. Theplot of Rainforest is driven by the subtle integration of twonarratives. The first is in the present and follows Corbett’s journey to thecamp, tensions with both his British and Mexican coworkers, and his unsuccessfulsearch for mantids. While these events are unfolding, he also becomes more openabout his past with Penelope, revisiting and revising what he has previouslyrevealed. Penelope, it turns out, was an acquaintance not a lover and her deathin a car crash occurred in the course of her flight from Corbett.He is, indeed, a stalker, who became obsessed with her after a single, short dinnerdate and who was the recipient of a lawyer’s letter and a policecaution. The pull and push between present and past, effect and cause,representation and reality retrospectively infuses previous passages with new (andsinister) meaning while heightening the narrative tension. To take just threeexamples, the novella opens with Corbett fondling something he calls his‘talisman’. I’ll avoid spoilers by not revealing precisely what it is, sufficeto say that the object seems to be a bizarre but harmless keepsake. Similarly, hisentomology seems to be a relatively insignificant part of his personality,perhaps even a narrative device to bring him to the jungle, but his expertise in mantid predation is no contingency. Finally, Corbett's reaction to an illustrationin a book seems either absurd, tangential to the plot, or both, but is a crucialcomponent of the narrative crisis.

WhileRainforest is neither didactic nor even a case of the ‘instructing bypleasing’ tradition of literature, it does explore a theme that is relevant toand resonates with everyday life in the twenty-first century. The novella exploresthis theme in a singular and inventive way and simultaneously reinvents theghost story as an aesthetic form. First, Paver asks us to reconceive or atleast reconsider ghosts as stalkers. Not stalkers in terms of the denotation ofthe word, the hunting of humans or animals by other humans or animals, but inthe legal connotation of men stalking women with whom they have becomeobsessed. Regardless of whether they were perpetrators or victims, ghosts aredead things that are obsessed with an aspect of their animate lives – eitherwith the places where they lived or died or with people whom they despised orloved. Like the stalker, the ghost is an unwelcome and uninvited presence thatdisturbs and disrupts the mental (and sometimes physical) wellbeing of theperson it haunts or of the people who enter the place it haunts. Aside from andin addition to the richness of this thematic exploration of what ghosts are,Paver reverses or inverts the traditional ghost story in and with Rainforest,presenting her readers with a (living) person stalking a (dead) ghost. Whereone might expect Penelope to stalk Corbett from beyond the grave in revenge, itis Corbett’s pathological fixation that fails to recognise death as animpediment. As he stalked her in life, so he continues to stalkher in death, deluding himself that he is driven by guilt rather than acceptinghis predatory desire to possess her against her will. I can’t recommend thisbook enough. If you haven’t yet discovered the pleasures of Paver,follow up with Thin Air, Dark Matter…and Wakenhyrst too.